In the forty years following the Great Chinese Famine, China managed an achievement of almost fish-and-loaves proportions: It fed 20 per cent of the world’s population on crops harvested from less than 10 per cent of the planet’s arable land. This miracle of self-reliance, however, ultimately wasn’t sustainable and between 2008 and 2012, China doubled its imports of U.S. agricultural products; with annual sales of almost $26-billion, it is now the number-one market for the U.S.

China now faces a new food crisis – how to ensure steady food production for a population of approximately 1.4 billion people on dwindling agricultural resources. One potential solution remains hotly contested: genetically modified crops. The past five years have seen a steady increase in Chinese patent activity for crop breeding, leading experts to speculate on whether China is hoping that genetically modified agriculture will be the ticket to a heartier domestic breadbasket.

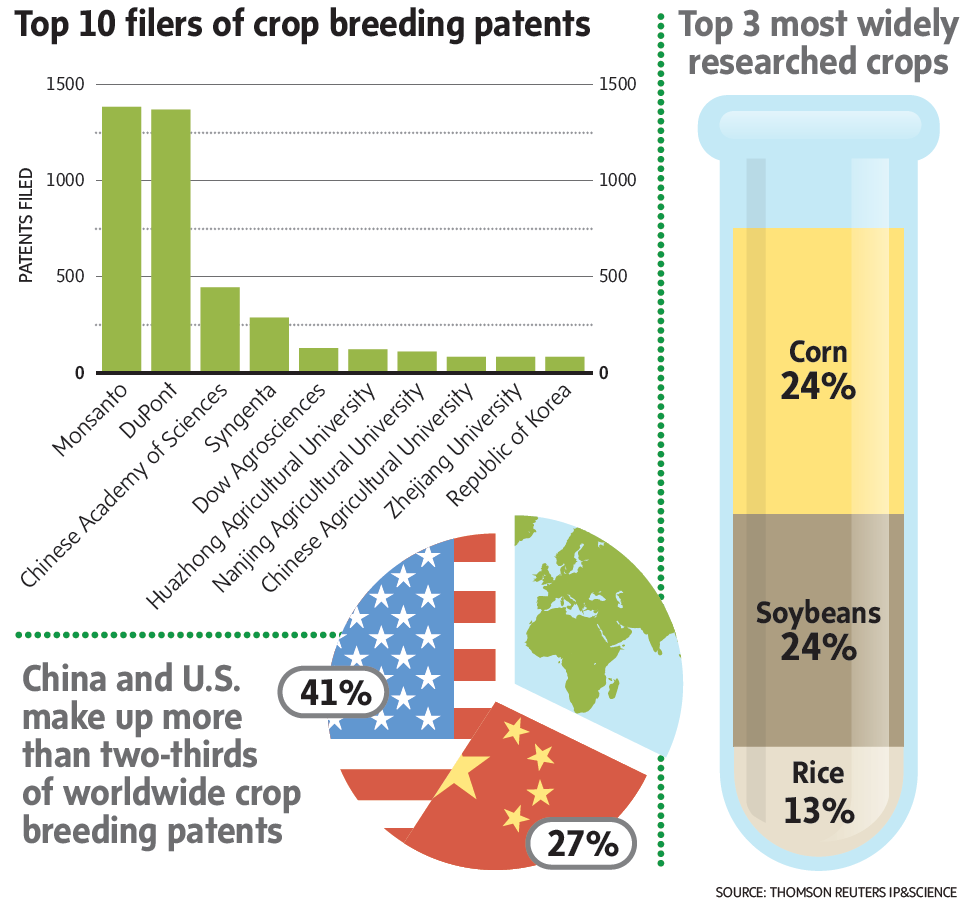

According to data from Thomson Reuters IP & Science, U.S. and China together accounted for 68 per cent of the world’s crop breeding patent documents between 2010 and 2014. (The U.S. lays claim to the top spot, filing some 5,000 patents during that period. China came in second, with around 3,000 patents. With a few hundred patents, Canada trailed in third place.) More than half of that activity was attributed to two U.S. companies, Monsanto and DuPont, though Chinese institutions make up half of the top ten.

“China is making a concerted effort to up the stakes in food production, and genetically modified (GM) foods will play a crucial part,” says Bob Stembridge, customer relations manager for Thomson Reuters IP & Science in the Nine Billion Bowls report released earlier this year.

Although China’s patent data doesn’t separate genetic technology on its own, recent events suggest the country has a strong interest in exploring the potential of GMO. Earlier this year, the Chinese government renewed permits allowing scientists at the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences’ Biotechnology Research Institute and Hashing Agricultural University to grow a GMO type of high-yield corn and two types of GMO pest-resistant rice in open fields, with an eye toward possible commercialization. At present, domestically grown GMO crops cannot be legally sold in China. The country does, however, import GMO agriculture from the U.S.

When Université Laval professor Bruno Larue sees this trend of increased patenting activity, one thought springs to the fore. “China is concerned about its food security,” says Larue, who holds the Canada Research Chair in International Agrifood Trade. He thinks the concern is less about a growing total population – the OECD actually records 0.6 per cent negative growth for China in 2014 – than it is about which segment of the population is growing the fastest: China’s middle class, and they’re hungry. “As Asian countries, China included, keep on developing, their consumers will increasingly want to consume more meat and dairy products,” says Larue. In fact, the OECD calculates that China’s meat consumption on a kilogram-per-capita basis is now 13 times higher than it was in 1985.

“Their agriculture productivity has grown rapidly,” he admits, “but there are concerns that such growth is not sustainable.” China’s unparalleled agricultural output growth averaged 5.1 per cent annually from 1985-2007, largely on the strength of increased total factor productivity (TFP), which is the ability to grow more food without using more inputs (land, labor, capital, material resources). Since then, China’s TFP has been in steady decline. (In July, China’s national bureau of statistics announced that agriculture sector growth, which already paled in comparison to services, manufacturing and construction, was down over the year previous.) Larue suspects China may have simply maxed out on just how much they can grow using what they have.

“China has a major water problem,” he notes. More than half of the country’s rivers have dried up due to over-industrialization in the past 65 years, leaving the agriculture sector with the daunting task of growing enough food for 20 per cent of the world population using only 7 per cent of its water. Even the controversial, just-launched South-North Water Diversion Project, a $50-billion effort to irrigate the arid north using 4.8 billion cubic meters of fresh water diverted annually from the relatively lush south, won’t be enough. The alternative, Larue suggests, is “investing in R&D to develop higher yielding GM varieties [as] part of their strategy to keep productivity up and try to feed themselves.” Indeed, Chinese president Xi Jinping has spoken publicly about his fear for China’s food security– and his support of GMO technology.

There are two methods for controlling an agricultural trait such as drought – resistance: natural plant variations and GMO technology. Natural plant variations is the traditional method; it involves crossing different genotypes of the same species to get new combinations of traits. (It’s a time-intensive process. Breeders will cross two variations and then look at a large number of progeny to select those with the most desirable traits.) GMOs, however, introduce genetic material from other species. Both methods, however, can result in patentable crops.

But Shawn Mansfield, professor in the Faculty of Forestry at the University of British Columbia, thinks GMO crops will be of limited use in the battle against hunger.

“There’s a place for it, but I don’t think it’s a silver bullet,” says Mansfield, who recently completed his term as Canada Research Chair in Wood and Fibre Quality. “If you look at the scientific publications, we produce enough food to feed [the current] number of people – but in places like Canada and the U.S., there’s a lot of waste.” A 2013 United Nations report estimated that one-third of all food produced worldwide – approximately 1.3 billion tonnes annually – goes to waste. But even if we could manage the impossible task of completely eliminating all that waste, says Mansfield, our current food production would be hard-pressed to keep in step with the 2.4 billion population increase that is expected by 2050.

“We’re producing crops relatively productively on about 80 per cent of the world’s arable land,” he says, “so we don’t have a lot of places to expand to in order to feed the population expansion that’s expected in the next 40 or 50 years.”

In theory, a GMO crop that produces higher yield using lower inputs (primarily water, fertilizer, pesticides and herbicides) could help meet this increased demand, and would be of great interest to China as it tries to revive its flatlining agricultural productivity. In practice, however, GMOs appear to have a long, uphill road to climb.

“The recent history of GMO crops have not been great,” says Lewis Lukens, associate professor of plant agriculture at the University of Guelph. A geneticist who mostly works in natural plant variations, Lukens has not observed GMO patents translate into performance on a game-changing scale.

“There have been very few new GMO events in crop plants in the last 15 years,” he says. “People have certainly tried to make genetic traits for things like drought tolerance, but those have not yielded what they hoped. Most of these traits are so complicated that it’s very difficult to find one or two genes that will [have a positive] influence. It’s more than one gene – it may be dozens – that are controlling a trait, and that’s very difficult to manipulate. The problem is harder than what people anticipated.”

He adds that even an exceptional seed, whether the product of traditional cross-breeding or genetic technology, would be of limited advantage without good agronomical practices. “If you don’t have that in place, GMOs aren’t going to help much.”

According to Thomson Reuters data, U.S. researchers published 1,243 papers about genetically modified crops or food during 2005 to 2014 – well ahead of second-place England (430 papers) and third-place China (413). Although Canadian researchers do publish work related to GMO – just under 300 papers during that nine-year period – Mansfield notes that, overall, there is a much “greater flavour for that technology in U.S. because the two major companies patenting in that area are U.S.-based.” In China, the vast majority of crop patents are filed by either the state-run Chinese Academy of Sciences, or the country’s top four public research universities – not a dominant private seed or crop producer. “It’s two different paradigms,” says Mansfield, and he doesn’t share concerns about farmers being forced into dependence on corporate seed producers.

“I don’t see any worries about this,” he says. “There are many patents issued on an annual basis, but to be frank, many of them are useless. The majority of these patents are protective patents. Yes, there are more and more patents being issued, but you’re not seeing the equivalent number of new crops coming online.

“Even if it’s patentable, if there’s no market, there’s no need to protect it. [But] China and U.S. feel differently because they have the bankroll.”

Although the rise in Chinese crop patents does not necessarily point to a future boom in GMO crops, Mansfield does think it reflects the success of the China Scholarship Council, an initiative of the Chinese Ministry of Education to help Chinese students get advanced degrees from the top universities in Europe and North America,o n the condition that they put their educations to work back in China.

“We’re seeing an increase in the number of papers [by Chinese researchers] being published in high-end journals,” says Mansfield. “New technologies and critical thinking are being brought back into the country and it’s starting to flourish.”

Thomson Reuters Know 360 App – Your mobile thought leadership library. Published by professionals for professionals, Thomson Reuters publications provide exclusive insights, ideas and information for the financial, risk, legal and scientific markets. Thomson Reuters Know 360 invites you to learn more and download the app for free to your tablet device or iPhone at thomsonreuters.com/know360app.

This content was produced by The Globe and Mail's advertising department, in consultation with Thomson Reuters. The Globe's editorial department was not involved in its creation.