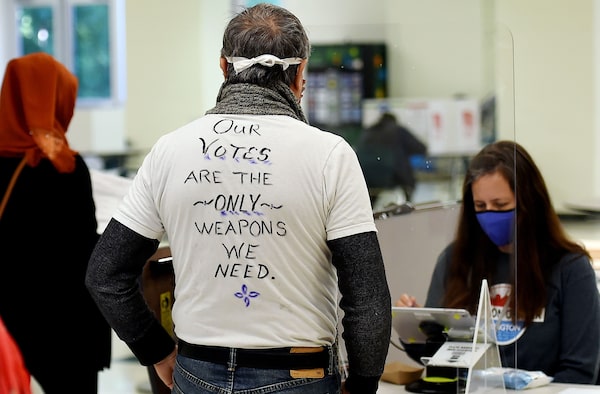

A voter wears a hand-written message as he arrives to cast his ballot at a polling station on election day in Arlington, Va., on Nov. 3, 2020.OLIVIER DOULIERY/AFP/Getty Images

For much of its history, Canada has been a lucky country, sharing the prosperity of its U.S. neighbour, tucked under its security umbrella, supporting a U.S.-led world order. The divided nation to our south on view during the 2020 election campaign has to make you wonder whether that luck is running out.

It was cast as a turning point for the United States – a “battle for the soul of the nation,” in the slogan of Democrat Joe Biden.

But the presidential campaign wasn’t much of a contest about the place of the United States in the world. Let alone what it means for its northern neighbour.

There are the same big-picture trends in the U.S. approach to the world, underlined by the country’s mood: Frustration with the costs of international leadership and the desire to withdraw from it, and the feeling the United States has to assert its own economic interests ahead of global principles. Those things weren’t really up for debate.

The U.S. is still wealthy and powerful, but no longer as dominant as it once was, with others, notably China, on the rise. But its own politics, after decades of foreign wars and job losses in manufacturing, are a force for U.S. withdrawal from world leadership.

One of the few things the supporters of Donald Trump and Mr. Biden seemed to agree on is that the U.S. is in decline. The cliché poll question asking voters if the country is on the right track or wrong track – usually a gauge of satisfaction with the incumbent – lost all meaning in 2020 because Republicans, too, said things are going badly.

In that mood, Americans just don’t have much time for the world. That’s been the trend for a while.

Mr. Trump stymied the World Trade Organization, warned NATO countries they must pay more, pulled troops suddenly out of Syria and has generally given the impression the U.S. isn’t taking responsibility for the world.

His America First promises in 2016 were no accident. Public opinion in the United States was concerned with domestic matters, exasperated that blood and treasure had been lost in decades of foreign wars, suspicious that the U.S. bore the cost of protecting others, and mistrustful of a trade system that cost them jobs.

But that trend didn’t start in 2016. Barack Obama also carried out a policy of withdrawing the U.S. from global leadership, in more subtle style.

Remember how the U.S. decided in 2011 that its role in Libya would be “leading from behind,” while encouraging allies to intervene? In 2013, Mr. Obama pulled back from his threat to strike Syria after it used chemical weapons – an action he had said would cross a red line.

The U.S. body politic still seems to feel global leadership isn’t worth the cost. Mr. Biden promised to work more with U.S. allies, and rejoin institutions, but didn’t campaign on leading the world, not on security, not on trading arrangements. The public was asking leaders to shield the country from the world, especially when it comes to economics and trade.

Who can say now which party, Republican or Democrat, is the party of protectionism?

For Canada, the main trade threat ended with the negotiation of the slightly changed Canada-U.S.-Mexico trade agreement. And the presidential campaign did display divisions on issues that affect Canada – Mr. Biden promised to act on climate change and cancel the Keystone XL pipeline from Alberta.

But the bipartisan political consensus is that the U.S. should encourage domestic industry, and Buy American – not North American continentalism that might exempt Canada from protectionist policies. That suggests skirmishes over access to the U.S. market will keep coming back.

U.S. voters have little interest in seeing their leaders revive free-trading rules. They want Made in America. And the idea of the U.S. leading the inexorable march to global trading rules is already being replaced by rivalry with China.

For non-superpowers, this great-power rivalry isn’t like the Cold War, which played out in arms races and proxy wars. Canada has already seen that closeness to the U.S. doesn’t prevent Beijing from taking punitive actions and economic retaliation.

Canada is still lucky to have the world’s wealthy superpower as its neighbour. But its mood about being a superpower has been sour for a long time. It is growing a little less willing to share its prosperity, or enforce rules, or lead the world order. Canada, which has framed so much of its own role in the world on its relationship with the U.S., is going to get used to it. The battle for the American “soul,” the turning-point election of 2020, didn’t suggest it will change.

Campbell Clark

Campbell Clark