Wayne Gretzky of the Edmonton Oilers, right, checks Guy Lafleur of the Montreal Canadiens in 1982.Ryan Remiorz/The Canadian Press

Guy Lafleur skated as smoothly and swiftly as an ice catamaran in a winter gale.

Streaking down the right wing with collar-length hair flowing behind him like a comet’s tail, he raised his stick before suddenly snapping down, the shot as devastating as the hammer on a mouse trap. Many a hapless goalie waved at the puck’s black blur.

The Montreal Canadiens star who was known to English-speaking fans as the Flower, a translation of a venerable family name traceable to feudal France, has died at age 70 after a recurrence of lung cancer. In his native French, he was le Démon blond, which better captured his essence.

Of his 618 career National Hockey League goals, including playoffs, perhaps the one that best expressed the right winger’s preternatural skill was scored against the Boston Bruins to tie the seventh game of their semi-final series on May 10, 1979.

With less than two minutes on the clock in regulation time and Boston short a player because of a sloppy penalty for too many players on the ice, Mr. Lafleur retrieved the puck from his goaltender, skated slowly behind his own net, then stopped on the other side before circling clockwise to avoid a forechecker. Danny Gallivan, the broadcast lyricist for the Canadiens’ symphonies, described the rest of the play for a national audience, his Cape Breton tenor fast rising to a breathless crescendo: “Lafleur, coming out rather gingerly on the right side. He gives it in to [Jacques] Lemaire, back to Lafleur, he scores!”

Gilles Gilbert, the Bruins goaltender, flung both arms out as he fell backward, looking mortally wounded. In just a few seconds, the Canadiens star had rescued his team from elimination; of course Montreal won the game in overtime on their way to winning a fourth consecutive Stanley Cup. Mr. Lafleur had willed it.

“In Quebec, hockey is a religion,” Pierre Larouche, a centre from Taschereau, once said, “and Lafleur is the new god.”

The player had come to the Canadiens hailed as a saviour, a natural successor to the demigods who preceded him. Maurice (Rocket) Richard’s passion for victory, his desperation to avoid humiliation, inspired a long-suppressed nationalism among French-speaking Québécois; he led the team to eight Stanley Cup championships.

The classy Jean Béliveau offered a mature leadership, an expression of a more self-confident society in the wake of the Quiet Revolution and the success of Expo 67; he skated on 10 Stanley Cup-winning teams. Mr. Lafleur, a lean 6 feet, 180 pounds, was the uneasy inheritor of such responsibilities. It was a heavy burden for a shy player from a rural Quebec village, who looked bashful even while being mobbed by teammates after scoring.

In time, he blossomed with a flair appropriate to the disco age, manoeuvring around opposing players as nimbly as he avoided the hot politics of his home province. He led the Canadiens to five Stanley Cups. The team has only won two since he left in 1984.

Lafleur leads a rush over the boards at the Canadiens' Stanley Cup-winning game against the New York Rangers on May 1, 1979.Charlie Palmer/The Canadian Press

:format(webp)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/2YM4RZAISBCEDGGNNYRSGWCMUE.JPG)

:format(webp)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/FBRMZD756FFF3FGCY4IIWQJSLU.JPG)

In civilian clothes, Mr. Lafleur, whose soft features and dimpled cheeks made him look more boy-next-door than Hollywood idol, was diffident and soft-spoken, even among adoring fans.

There was one place in the spotlight in which he was at ease. “Every time I was on the ice,” he said, “I was the happiest guy in the world.”

A nimble, effortless skater, in full flight he was a jet dodging biplanes. As he started a rush up the ice, fans at the Forum left their seats to cry, “Guy! Guy!” In the second half of the ’70s, from the time Bobby Orr was hobbled by a knee injury to Wayne Gretzky’s fruition, the Canadiens star was peerless.

He was the first NHL player to record six consecutive seasons of 50 goals or more and 100 points or more.

As well as the five Stanley Cup titles, Mr. Lafleur won the Hart Trophy twice as the league’s most valuable player (1977, ’78), as well as the Conn Smythe Trophy in 1977 as the playoffs’ most valuable player. The forward won the Art Ross Trophy three times as the league’s top points scorer, an achievement attained by Mr. Béliveau only once and by the Rocket not at all.

Mr. Lafleur also won the Lester B. Pearson Award three times as the league’s outstanding player as voted by fellow members of the NHL Players Association. (The award has since been renamed the Ted Lindsay Award.)

Lafleur in 1977 with the Art Ross, Conn Smythe and Hart trophies.Chris Haney/The Canadian Press

He was first heralded as Quebec’s next hockey great at age 11. His NHL debut was complicated by expectations that he seemed at first incapable of fulfilling. At the same time, the greater his success the more he came under scrutiny, his patronage of downtown bars and the status of his marriage becoming tabloid fodder.

Whatever his flaws and foibles, Mr. Lafleur, who accurately complained, “I can never do anything without the whole world knowing,” never lost the adoration of his fans.

Guy Damien Lafleur was born on Sept. 20, 1951, in Thurso, a village on the Quebec side of the Ottawa River. He was the only son of five children born to Pierrette (née Chartrand) and Réjean Lafleur, a welder at the pulp mill with a sulphurous odour that permeated the company town about 40 kilometres downstream from Ottawa.

Little Guy skated for hours on the backyard rink made by his father. The boy slept in hockey gear, except for skates, so he could be on the ice as early as possible next morning. Some dawns, he sneaked into the warehouse-like arena a few blocks from the family home to work on his skating and his shot. “Guy was always more interested in hockey than school,” his father once said.

He first appeared in headlines at an international peewee hockey tournament in Quebec City in 1962, scoring 16 goals in six games to win the Red Storey Trophy as the tournament’s most valuable player. He won the trophy again in the 1964 tournament when he scored 17 goals in five games.

The peewee prodigy met Mr. Béliveau at the tournament. “Maybe one day,” Mr. Béliveau told the boy, “we’ll see you in the NHL.”

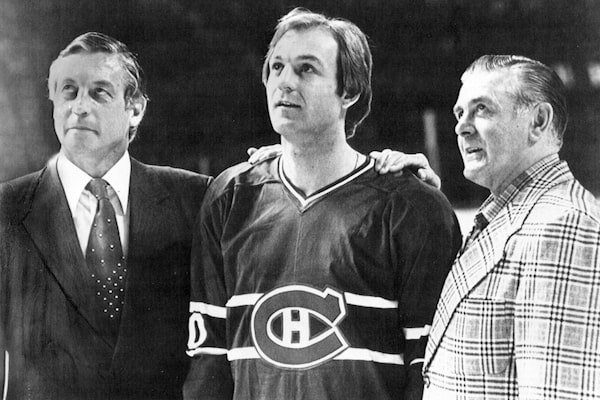

Lafleur with Jean Béliveau and Maurice Richard in 1979.Doug Ball/The Associated Press

In 1966, at age 15, the teenager left Thurso to play junior hockey in Quebec City with the Quebec Remparts. He wore Mr. Béliveau’s No. 4 sweater, the understudy scoring 130 goals in just 62 games of his final junior campaign while leading the Remparts to the Memorial Cup national junior championship.

Before that final junior season had even started, Montreal general manager Sam Pollock engineered a trade with the Oakland Seals to get their draft pick in the 1971 amateur draft. Mr. Pollock was convinced the sad-sack Seals would finish in last place, guaranteeing Montreal the first pick.

The next season, when his trading partners, renamed the California Golden Seals, came within five points of catching the Los Angeles Kings in the standings, the wily general manager helped keep the Golden Seals in the basement by dispatching veteran centre Ralph (Bulldog) Backstrom to bolster the Kings in exchange for two nondescript players. With Mr. Béliveau’s retirement looming, Mr. Pollock needed to ensure the dauphin would be his. The young scoring sensation was the first pick in the 1971 NHL amateur draft.

Mr. Lafleur served a tough, three-year apprenticeship, as campaigns of 29, 28 and 21 goals were inadequate for fans expecting greatness. The dissatisfaction with the Flower as a shrinking violet changed overnight when the player at last blossomed into a goal scorer in 1974-75, coincidentally the season when he abandoned wearing a helmet.

After winning the Stanley Cup in 1978, aided by the winger’s overtime winner in Game 2, Mr. Lafleur orchestrated the trophy’s abduction, escorting it on a tour of favourite nightspots before arriving in Thurso in the morning to show it to his father.

From endorsing Bauer skates and Koho sticks, he became a pitchman for Yoplait yogurt, Zeller’s, automobiles, stationery, Shasta pop and Molson beer. The star player also released his own product lines, including maple syrup, a table-hockey game, a cologne called Guy Lafleur No. 10 and, in 2020, a line of five different wines carrying his name. In his heyday, he also recorded Lafleur!, an album of hockey instruction voiced by the player over a disco beat.

His popularity was so great that he found it impossible to enjoy such simple pleasures as taking his first-born son shopping for toys, as he would be mobbed by well-wishers and autograph seekers. His public discomfort was made worse when police informed him of a credible kidnapping threat by gamblers who had just completed a daring armoured car robbery in 1976.

In 1981, he fell asleep at the wheel driving home from Thursday’s, a favourite haunt on Montreal’s Crescent Street, crashing his rented Cadillac Seville into a guardrail. A metal post stabbed through the windshield, skewering the steering wheel and slicing his right ear. He missed death by a whisker only because he had fallen asleep slumped to his left.

On the ice, he was slowed by injuries in the 1980s – tonsillitis, a charley horse, a pulled hamstring, a pulled groin, a blackened eye, another hamstring injury and a bruised ankle. He scored just two goals in the first 19 games of the 1984-85 season, his playing time limited and his wild, instinctive rushes thwarted by a suffocating defensive system employed by coach Jacques Lemaire, who had been his centre on a line with Steve Shutt in the glory seasons.

Lafleur warms up on centre ice in Montreal in 2003.Christinne Muschi/Reuters

:format(webp)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/32CO2KWMWRF4DNLNYGTAW77ARA.jpg)

:format(webp)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/MPAPABL7I5BIXAFXIDMERSMT3M.JPG)

Mr. Lafleur abruptly retired as the all-time greatest points scorer in Montreal Canadiens history. Three years later, he was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame before, surprisingly, returning to the NHL to play for the New York Rangers. He concluded his playing career where it started by skating for two seasons with the Quebec Nordiques.

In addition to product endorsements, paid public appearances and his role as a public-relations ambassador for the Canadiens, Mr. Lafleur was involved in a number of businesses, including restaurants. He also got a helicopter pilot’s licence.

In 2008, he was arrested on a perjury charge after giving contradictory testimony at his son Mark Lafleur’s criminal trial. The former player was convicted in 2009, though the verdict was overturned on appeal the following year. He then sued police and prosecutors for $2.16-million, alleging he had lost endorsement income. A Quebec Superior Court justice ruled Mr. Lafleur’s case was without merit.

In September, 2019, Mr. Lafleur underwent quadruple bypass heart surgery and three months later had a lobe removed from a lung. In October, 2020, he announced the lung cancer had returned and he began immunotherapy and chemotherapy treatments at the Centre hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal (CHUM), where he had earlier undergone surgery. A heavy smoker, the star player was known to light up cigarettes even between periods of a hockey game.

Mr. Lafleur leaves the former Lise Barré, his wife of 48 years; his adult sons Mark and Martin; mother, Pierette; granddaughter, Sienna-Rose; and four sisters.

Mr. Lafleur was named an officer of the Order of Canada in 1980 and was named to the Order of Quebec five years later. The NHL included him in the league’s unranked listing of 100 greatest players of its first century.

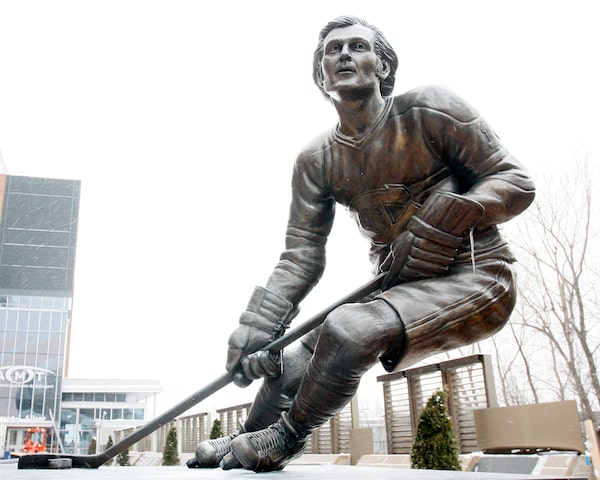

The Canadiens retired his famous No. 10 sweater in a ceremony in 1985. As well, a bronze statue of the player has been erected on a plaza adjacent to the Bell Centre in Montreal, where he is joined by Howie Morenz, the Rocket and Mr. Béliveau.

A welcoming sign in his Thurso birthplace declares it to be the “Ville de Guy Lafleur.” The old arena carries his name, as does an adjacent street.

For all the honours and the adulation, Mr. Lafleur once told Wayne Parrish of the Toronto Star that he was happiest skating in an empty arena, as he had done as a boy.

“There is nobody yelling at you, telling you what to do,” he said. “You are free.”

A statue of Guy Lafleur in Centennial Plaza outside of the Bell Centre.Richard Wolowicz/Getty Images