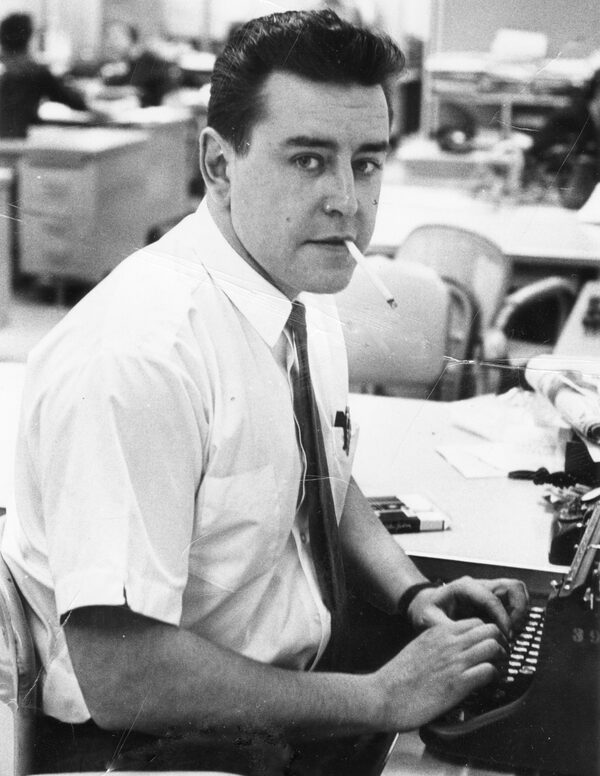

'I was always envious of Dad,' Globe foreign correspondent Eric Reguly writes of his father, Robert, shown here in South Vietnam in 1967, wearing U.S. Army fatigues he bought shortly after arriving in the country as a war correspondent. 'He went to Vietnam and covered history; I only heard the stories.'Photo research by Paula Wilson • Graphics by Trish McAlaster

Chevy Chase, Md., summer 1967

It’s early one morning in late July or early August. I am a nine-year-old excited to see my father, who has just returned from almost three months in Vietnam. I creep into the bedroom and leap onto his chest, expecting him to hug me, laughing.

In an instant, I am flying backward gasping, clutching my chest.

He didn’t mean to punch me. He was still in his foxhole.

Rome, January, 2018

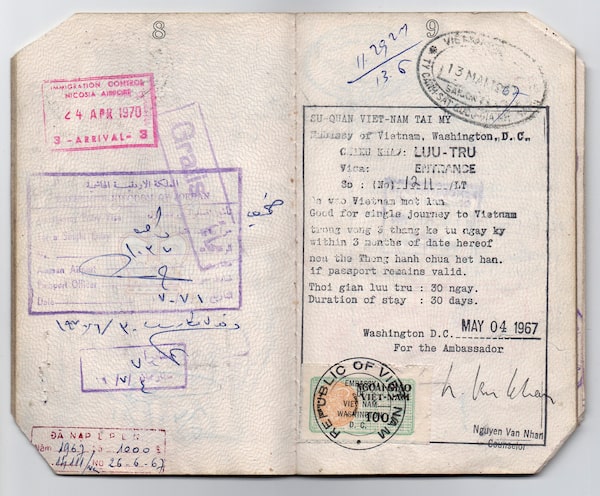

Finally, I am packing for my flight to Ho Chi Minh City, still better known as Saigon. Even before the death of my father, Robert Reguly, in 2011, at age 80, I had dreamt of retracing his steps during the war, which he covered for the Toronto Star when he was 36, in the peak years of his career. At the time, he was the Star’s Washington bureau chief and Canada’s most famous print journalist.

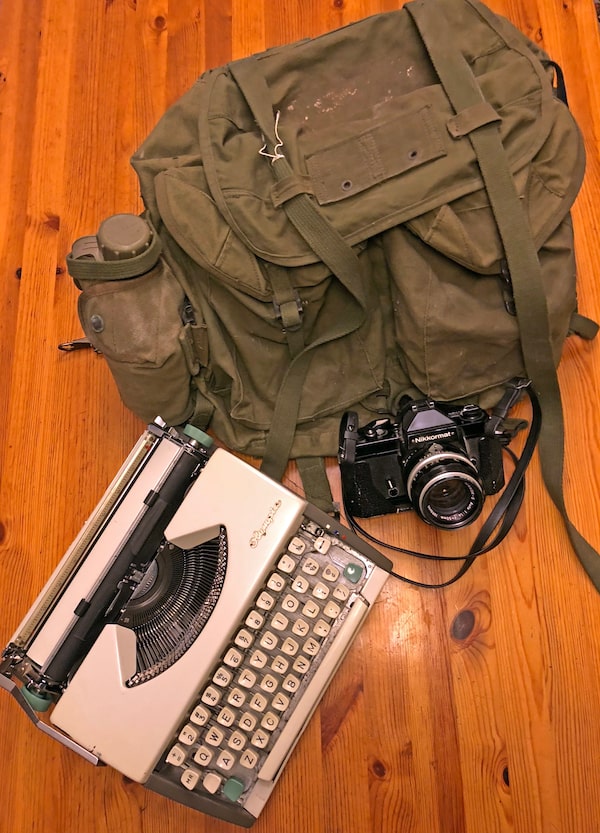

Three precious objects in my home office in Rome demand my attention as my bags fill up – yea or nay. The first is the German-built Olympia portable typewriter that Dad – known as Bob to his family and friends – lugged around Vietnam. It has a couple of dents, but works perfectly. The second is a brick-heavy Nikkormat camera, black, one of two he used as a foreign correspondent in the United States, Indochina, the Middle East and Africa. It, too, works perfectly. The third is the U.S Army knapsack, complete with insulated green plastic water bottles, that he bought on the black market the day after he arrived in Saigon in May, 1967, and carried into war.

Robert Reguly's tools of the trade in the Vietnam war: His Olympia typewriter, Nikkormat camera and green U.S. Army knapsack.Eric Reguly/The Globe and Mail

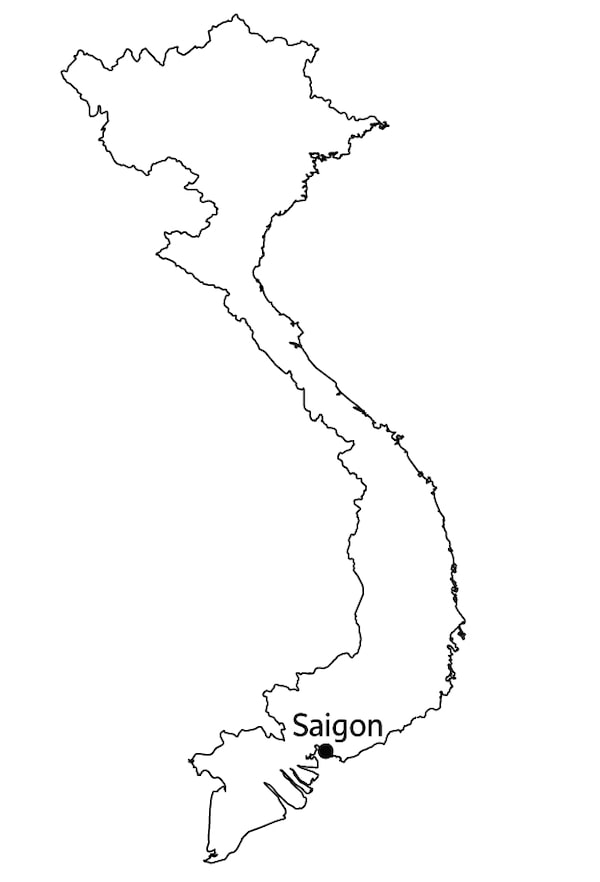

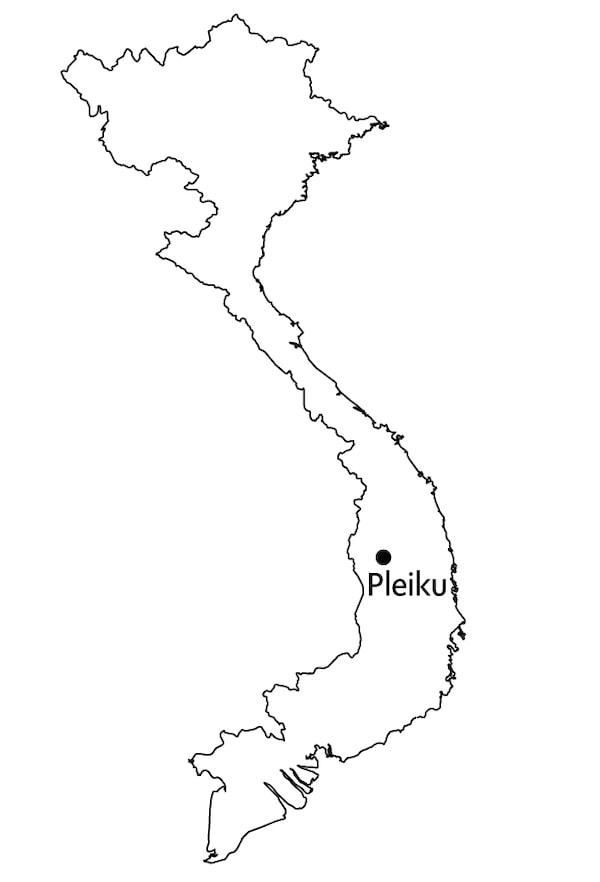

How romantic. Why not take pictures in Vietnam with his camera, write on his Olympia, and traipse across former battle zones with his knapsack. In the end, none of the three makes the cut. Looking at my map of Vietnam, now splattered with pink dots, each marking a spot he had visited (or close enough), I realize I will be on the move constantly, without the benefit of a Huey helicopter. Best to travel light.

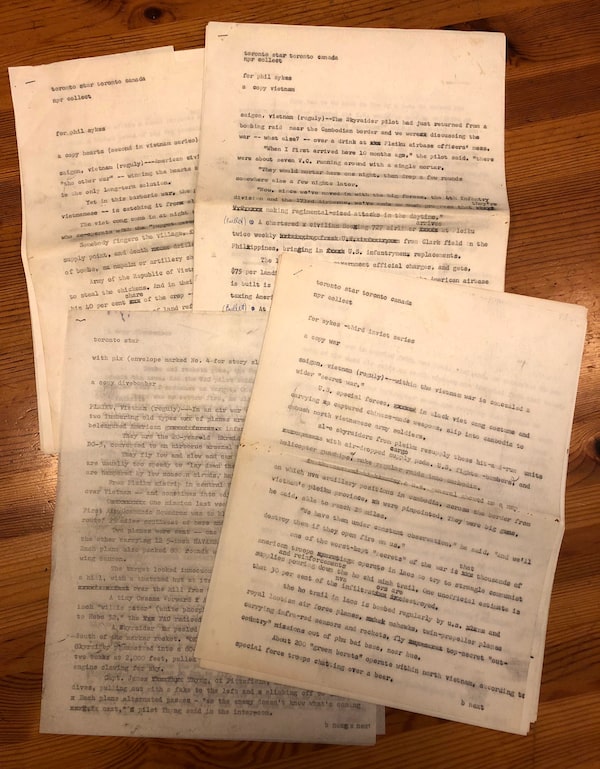

What does make it into my bags, other than the requisite Dispatches, Michael Herr’s hallucinogenic book on the war, are copies of the original stories Dad banged out in Vietnam, retrieved from a musty filing cabinet in my mother’s Toronto basement.

Their place lines – Saigon, Pleiku, Hue, DMZ, Plei Beng and others – will be my compass. I had grown up hearing these names over and over, but I never knew where they were, what precisely happened in them.

I’m not even sure they still exist. Would they now be covered by forest, highways or malls, or seared into moonscape by bombs and Agent Orange?

What I did know is that these spots forever changed my father and, by extension, his family, especially me, his oldest child and only son. When I was young, I regarded my father as a semi-mythical figure, a fearless truth warrior forever dashing off on dangerous assignments, even if I suspected by then that he would never be a model father or husband. He was always travelling, always working. I remember him taking me to early-morning hockey practice but I don’t remember him coming to an event at school – no parent-teacher meetings, no concerts.

At the time, his faults didn’t really bother me – I just wanted to be like him, a hard-living daredevil with a typewriter. While I would never become a “bang-bang” correspondent, to use the journalist argot for war reporter, our careers would have a few notable similarities. I am based in Rome for The Globe and Mail, covering Europe, North Africa and the Middle East. My father was based in Rome for the Toronto Star from 1969 through 1972, covering the same territory, and beyond. We both had U.S. postings – Dad in Washington, me in New York – and long stints as investigative reporters.

I would be lying if I said I had not felt competitive with him over the years. When he praised my stories, my spirits would soar. When he thought they were lame, naive or insufficiently critical of power in any form, my heart would sink. “Beneath your veneer,” he would sometimes say, laughing, “there’s more veneer.”

Through Bob Reguly, I became aware of the world. Through him, I experienced Vietnam vicariously, making me wish I had been born 20 years earlier, so I, too, could have jumped on Hueys as if they were taxis, skimming over the lush Vietnamese forest on the way to a battle, then back in time for martinis in Saigon. It’s not that I have a taste for gore. But in my mind, and my father’s, the Vietnam war was the biggest event of its era. If you were a journalist and didn’t go to “Nam,” you missed out one of America’s greatest and most tragic geopolitical sagas, a wound that has yet to heal.

The war did not zap my father with a heavy dose of post-traumatic stress disorder. My mother, Ada, agrees that the destruction and bloodshed he saw did not shake him terribly, even if he returned from Vietnam skinny, wild-eyed and taut as a violin string. My father would tell me the only event he covered that truly shattered him was Bobby Kennedy’s assassination, in Los Angeles in 1968. Dad was standing not 10 metres from him when the shots rang out. He watched Kennedy blink a few times as he lay on the kitchen floor of the Ambassador Hotel, dying.

Still, Vietnam changed my father. He came back hating the war, hating American foreign policy – contempt that would stay with him for the rest of his career, especially in the Middle East. He was convinced the war was unwinnable in spite of U.S. firepower. In spite of reassurances from President Lyndon B. Johnson and Defense Secretary Robert McNamara that the war was just and being won. In spite of broad popular support for the war. In spite of the inconceivable notion that a country that had defeated Japan and Germany could be overpowered by a tiny nation of rice farmers.

My mother says: “He told me the Americans way overdid everything. They would come across a village and see someone working in the garden and they’d drop a bomb on them. How did they know they were Viet Cong? They didn’t.”

Oh, one other thing. My father thinks he killed a man, or men. Journalists are not supposed to do that. But I wanted to find the spot where he fired his M-16 machine gun.

Eric's first stop in the Vietnamese capital is the Majestic, a French colonial-era hotel frequented by journalists, officers and other foreign visitors during the war. Robert stayed there in 1967.Eric Reguly/The Globe and Mail

Saigon, January, 2018

The Majestic, built in 1925, is a tired but glamorous French colonial pile that, along with the Rex, the Caravelle and the Continental, was stuffed with journalists, spooks and military types during the war years.

John F. Kennedy, then a U.S. senator, visited the Majestic in 1951. In those days, the French were still fighting Ho Chi Minh’s communist-nationalist forces; seven decades of colonial rule would not end until the Battle of Dien Bien Phu three years later. Other guests over the years have included Somerset Maugham, Catherine Deneuve and Graham Greene, author of The Quiet American, the prescient tale, published in 1955, about misguided American interventionism in Vietnam. Evidently, JFK, after he was elected president in 1960, did not take the book to heart. Nor did his successor, LBJ.

It is to the Majestic I head when I arrive in Saigon on Jan. 29. It’s in the heart of the city and faces the muddy brown Saigon River, now flanked with construction projects and Heineken billboards. At the front desk, I ask if guest records go back to the 1960s – Wouldn’t it be cool to stay in the same room my father did? The receptionist laughs: “That’s a long time ago. No computers then.”

I head to the open-air terrace on the fifth floor, where Dad would have drunk and dined. He told me it was from here that journalists watched American bombers return to Saigon, occasionally seeing the distant sky turn pink as napalm strikes incinerated the forest. The Viet Cong guerrillas were never far away.

It’s late and there is only one fellow guest on the terrace, an elderly man with snow-white hair. He’s having a drink and looking out across the river. I say hello and he invites me to join him. He is Frank Tapparo, 80, from Hershey, Pa. He was an Army major during the war, working at the Department of Defense’s communications planning group, “a secret organization,” he tells me, “that did not exist.” And he had stayed at the Majestic whenever he was in Saigon.

Its mission was to line electronic sensors along the Ho Chi Minh trail – the vast logistics network that delivered men and munitions from North into South Vietnam via Cambodia and Laos. The sensors, dropped by aircraft, would embed themselves into the ground and detect vibrations made by passing trucks, delivering a radio signal to an overhead electronic-warfare plane, which in turn would call in the bombers. “Yes, it all worked,” Mr. Tapparo tells me. “But there were so many trucks coming down the Ho Chi Minh Trail all the time, the question was: Did we really need these sensors?”

Eric poses for a picture with Frank Tapparo, 80, a former U.S. Army major also staying at the Majestic.Eric Reguly/The Globe and Mail

Mr. Tapparo is making his first trip to Vietnam since 1970 and says he doesn’t recognize Saigon. Today, it is a vast, noisy, skyscraper-ridden tangle of some 12 million people and more than eight million scooters flowing through the streets like schools of fish. “I can’t believe it,” he says. “It looks like Tokyo.”

Not that Saigon was a pretty place during the war. “The leaves were dying on some of the trees,” he says. “The soot and exhaust fumes from all the military traffic covered everything. We’d get rocketed a couple of times a week from the swamp across the river. I would always take an interior room for protection.”

I ask Mr. Tapparo if he had known the Americans would lose the war, and if he thought the media had accelerated that loss. Yes and yes, he says, but “the reporters like your father weren’t reporting fake news. We had some people who did some bad things here, for sure. I fought an honest war. But it was a war that should never have happened.”

He wishes me luck on my voyage of discovery: “You’re doing for your dad when I am doing for myself.”

Robert Reguly's visa for entering Vietnam, stamped by the Vietnamese embassy in Washington, D.C., where he had been based as a Star bureau chief.Eric Reguly/The Globe and Mail

Drafts of Robert's dispatches from Vietnam. His stories and editing notes were Eric Reguly's guide for his own Vietnam journey.Eric Reguly/The Globe and Mail

The demilitarized zone, early February, 2018

About half a year before my father died of heart disease, diabetes and who knows what else – he had been a heavy smoker and drinker, and never watched his diet – I asked him to jot down a few notes about his Vietnam experience. He was fading fast and didn’t get far, leaving me about 1,000 words. Those notes, combined with 20 or so Toronto Star stories, a few of his war photos, my mother’s recollections and a couple of serendipitous encounters with other veterans, allowed me to piece together his journey across Vietnam and within himself.

Bob Reguly did what all good newsmen do when they step off a plane – find the action fast. Given total freedom to go where they wanted when they wanted, journalists in Nam hopped onto planes and helicopters on a moment’s notice. And although they were not “embedded,” as later correspondents would be in Iraq and Afghanistan, they were given the rank of major – field-grade military officer, above the rank of captain – giving them access to officers’ canteens and to cots at military bases. They were even given rifles, and were encouraged to fight when U.S. soldiers were getting gunned down: The boys had more pressing things to do than protect war tourists from the North Vietnamese Army and the Viet Cong.

Within two days of arriving in Saigon, Dad had bought his U.S. Army gear, checked out of the Majestic, and boarded a C-130 Hercules military transport plane to the Phu Bai combat base, just south of Hue, the ancient imperial capital, in central Vietnam. What he didn’t know was that he would end up in the Demilitarized Zone, the DMZ.

Nor did he know that this 10-kilometre-wide no-man’s land that separated North and South Vietnam – “the Z,” as the soldiers called it – was about to take its place in military history.

I will let my father’s notes to me pick up the story from here:

“When the Herc landed [at Phu Bai], I walked directly to waiting helicopters along with the 700 Marines of the Third [Battalion] of the Fourth Marine Regiment. Only then I was told we would be invading the DMZ.

The Americans claimed that the North Vietnamese were stashing supplies inside the DMZ, for smuggling onward to the Saigon area, as rationale for the invasion. We formed a 700-metre perimeter of an elongated U, with the open end smack on the Ben Hai River ... The temperature was in the 90s.

Four days later there were only 300 of us original 700 left. Most of the casualties were from heavy fire – 122-mm Soviet shells that left a hole in which you could bury a small car. The Viets would trundle three or four guns out of the caves, lob several rounds each and push the guns back in the caves before the U.S. dive-bombers circling above could get a bead on them.

One incident I witnessed: Marine snipers were trying to hit a Viet strapped high in a tree outside the perimeter, obviously radioing corrections to the artillery fire. But he kept ducking behind the trunk. The Americans flew in an Ontos tank in a Chinook copter ... The Ontos had three 105-mm recoilless rifles on each side of the turret. The Ontos churned up the perimeter, let fly with all six barrels. All that was left was a stump.

At night, there would be an exactly 20-minute mortar barrage, followed by NVA running through, shooting Kalashnikovs and throwing grenades. In the morning light, there would be bodies from both sides, some still screaming from wounds. There were three run-throughs a night. Each time, I dug my foxhole deeper.

After the first night, a Marine lieutenant told me the NVA can’t tell you’re a journalist in the dark. So I got a quick lesson on the M-16 and used it the next three nights. It was chaos, with everybody shooting, so I never knew whether I killed anybody, but I may have.”

My father had unwittingly stepped into Operation Hickory, the first U.S. invasion of the DMZ, which in turn was part of the wider Con Thien battle, one of the war’s biggest and deadliest running battles – it would not end until early 1969.

In Dong Ha, a rough-hewn city that was home to the northernmost Marine base, and where my father had spent a night or two, my young Vietnamese guide and interpreter, Nhung, and I meet Ray Wilkinson, a former Marine who returned to Vietnam four years ago to teach English. “Your father’s note absolutely rings true,” he says. “It was a huge, huge bombardment. It was terrible.”

May 17, 1967: A U.S. Marine corpsman leads a wounded comrade, foreground, as others carry bodies toward a helicopter in Con Thien, Vietnam.Associated Press

Operation Hickory finished in late May, 1967, with the Marines taking 142 killed in action (KIA) and almost 900 wounded after running into two well-armed NVA battalions. The Con Thien casualties, and other slaughterhouse battles like it, had a profound effect on the psyche of the American public. They would help put the lie to propaganda that the Americans were on the verge of outright victory.

Years after the war, I would ask my father whether he regretted pulling the trigger when he was in his foxhole. “What was I supposed to do?” he asked me. “What would you have done?”

At the War Remnants Museum in Saigon a week after I leave the DMZ, I visit an exhibit titled, simply, Requiem. Put together by two legendary Vietnam War photojournalists, Tim Page (the model for the photographer played by Dennis Hopper in Apocalypse Now) and Horst Faas, Requiem features pictures shot by photojournalists, on both sides, who died covering the war.

One was Sam Castan, a Brooklyn kid working for Look magazine, who went down fighting as he fired a pistol at NVA troops. This is what the former CBS journalist John Laurence wrote about him:

“Sam Cast died fighting. He was a civilian journalist who became a warrior in the last minutes of his life – leading a small desperate group of American soldiers out of a trap, saving their lives, losing his own ... There were no easy choices in Vietnam. Every reporter and photographer who worked in the field worried about this one: What do you do when faced with the likely prospect of death? Pray for a miracle? Fight back? Try to surrender? Die passively?”

As I stared at the photos, I got a greater understanding for why my father and some other journalists – calling them “brave” is an understatement – sometimes had to battle their way to safety. Dad fought because he was expected to, had to, when the fighting turned against the soldiers who could no longer protect him. And he found himself standing alongside those soldiers because, for the most part, he refused to cover the war from the safety of Saigon, and rarely attended the U.S. press briefings (known among reporters as the Five O’Clock Follies) that were infamous for their inflated enemy body counts. My father and other correspondents risked their lives in firefights. And because of that, TV screens, newspapers and magazines in America and around the world featured real images of dying soldiers, burnt children and levelled villages. Journalists delivered those images, and many of them died doing so.

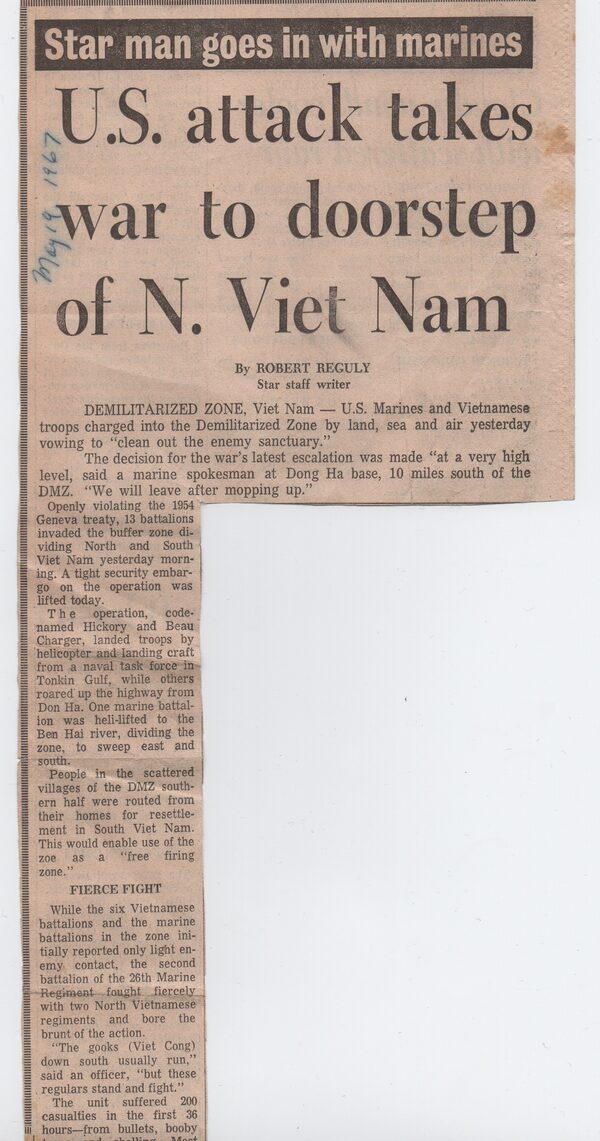

Robert Reguly made the Toronto Star's front page on May 19, 1967, with his report from the DMZ.Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

Dad’s story on the DMZ battle appeared on page one of the Toronto Star. Beneath a banner that read “Star man goes in with marines” and the headline “U.S. takes war to doorstep of N. Viet Nam” lay a story that was not nearly as gripping as the note he would leave for me more than 40 years later: The DMZ battle was his first assignment in Vietnam and he had mistakenly taken it as routine, admitting to me in later years that he had “badly underreported that episode.”

Still, the Star story was not without its horrors, chronicling the rage of American soldiers as “village women came out to strip Marines dead of their watches, canteens and rain ponchos”; the nighttime digging of foxholes into the “red gumbo”; the jolt of witnessing a soldier “jerked with a bullet between the eyes.”

And yet, amid the carnage, Dad worked hard to chronicle the humanity that frames all war. “We captured a Viet Cong down south near Chu Lai,” he quotes one major as saying. “He took me to his home and showed me a picture of his brother on the wall. The brother was in South Vietnamese uniform.”

On my current journey, I desperately want to find the spot where my father had gone in with the Marines.

I know he had dug in next to the Ben Hai River and that he thought he was some 80 km west of the Gulf of Tonkin, which seems a bit too far west to me. At our hotel in Dong Ha, Nhung and I pore over maps. Mr. Wilkinson, the former Marine, is staying in the same hotel and is pretty sure the Marines punched into the DMZ due north of the Marine combat base at Con Thien, which makes sense to us.

A C-130 Hercules transport plane sits near a bunker at the Khe Sanh battle site.Eric Reguly/The Globe and Mail

Eric stands in an American trench at Khe Sanh. In 1968, the base near the DMZ was one of the most famous battlegrounds of the war, with U.S. forces besieged by the North Vietnamese and forced to withdraw.Eric Reguly/The Globe and Mail

The next day, we hire a local guide, Nguyen Thi Thanh Hai, and visit Khe Sanh, one of the most famous battle sites of the war (it plays a big role in Dispatches), then loop back along Highway 9, travelling past other spots that saw fierce fighting – including the Elliot Combat Base (a 240-metre-high hill known as the Rockpile); and Cam Lo, another hellhole my father visited – before swinging north to the Con Thien area.

Hai explains that we can’t actually drive into Con Thien – it’s a two-kilometre walk, and once you get there, there’s nothing to see. So we head to the Ben Hai River and find two bridges that lie due north of Con Thien.

This must be the spot, or close to it.

One of the bridges is modern and busy with traffic. A footbridge lies a couple of hundred metres downstream, and that’s where we head, crossing to the southern bank of the Ben Hai.

Eric Reguly on the Ben Hai River: In search of his father's foxhole

The Globe and Mail

I tell Hai that I want to walk along the riverbank, away from the noise pounding its way out of a karaoke bar across the river, to look for clues of the butchery and chaos my father reported on all those years ago. But my fanciful plan to conduct this reporting of my own slams up against the violence that, decades later, echoes throughout much of Vietnam.

Hai glares at me, thrusting her right hand in front of my face. It is covered in scars: shrapnel wounds from a cluster bomb that exploded at her school many years after the war, when she was 6. The whole region, she says, is littered with thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands, of unexploded ordnance – UXOs. Three foreign-funded charities, among them Project Renew, remain busy removing them from the bombed-out province that includes the DMZ area. Dong Ha has a small, chilling museum devoted to the effort. Since 1975, UXOs have killed or injured more than 100,000 Vietnamese.

No, I will not be looking for my father’s foxhole. I would need to search out his presence elsewhere.

Duc Co Special Forces camp, 1965: Wounded soldiers crouch in the dust as a U.S. helicopter takes off from a clearing. This was one of many images taken by photojournalist Tim Page that chronicled the Vietnam conflict.Tim Page

Rome, autumn, 2017

If I am to pick the precise moment when I knew that, some day, I would make the journey on which I now find myself, it would be the spring of 1998, when I travelled to Manhattan to meet Tim Page, a hero of mine since I first read about his astonishing life in Dispatches. At the time, Mr. Page, a Brit, and Horst Faas, a German, had just finished their Requiem project, which took the form of a coffee-table book and a travelling gallery show (one I would see again at Saigon’s War Remnants Museum).

I spent the afternoon with Mr. Page on the Upper East Side’s Newseum, mesmerized not just by the haunting photos taken by the fallen cameramen and camerawomen (look up Dickey Chapelle for an example of female combat bravery) but by Mr. Page himself.

He and his photographer buddies were wild men, often doped to the gills, addicted to Jimi Hendrix and the Rolling Stones, riding to assignments on motorcycles, and producing some of the greatest photos of the war. In 1969, a hunk of mine shrapnel removed 20 cubic centimetres of his brain, and he wasn’t expected to live.

Mr. Page urged me to go to Vietnam. It would become an unfulfilled dream assignment until 20 years later.

A month before I finally leave for my trip, Mr. Page and I have a long Skype call, during which he smokes several joints and talks about the freedom that journalists like my father had – unimaginable today. “You could wander aimlessly through the country, hitchhiking by plane, by chopper, by boat,” he says. “You were entitled to walk into any officers’ mess and get decent chow ... Beautiful women, great food, great dope, great beaches. It’s as if the American military let us go feral.”

No wonder my father was able to cover so much ground in Vietnam, and get such great access. Don North, a veteran of 15 wars who spent a total of five years in Vietnam, some of them as an ABC News correspondent, and who later became a close friend of my father, told me over a recent dinner in Rome that covering the war was a thrill. “I remember the feeling of exhilaration of heading back to Saigon after a day running around the field and having a good story. We’d be flying back, with the fresh jungle air coming into the helicopter, skimming over the trees, and it was: ‘Wow, what a great job we had!’”

His words called up memories of my father: The close calls, the adrenaline rushes, the adventure, the sheer freedom, the daily – hourly – journeys into the unknown. When he talked to me about Vietnam, Dad’s face would light up like a candle.

Robert Reguly and his wife, Ada, on their wedding day in Sudbury in 1956. A decade later, they had three children and lived in Chevy Chase, Md., where Robert rubbed shoulders with Washington's power brokers. Ada recalls the family's time in Chevy Chase as the happiest of her life, Eric recalls, but her husband's long absence during the war nearly destroyed her.Handout

Chevy Chase, spring, 1967

Bob Reguly was given the Toronto Star’s Washington posting in the summer of 1966, a reward for having won two National Newspaper Awards for investigative journalism. The first of those award came in 1964, for his work tracking down a notorious fugitive from Canadian justice, Hal Banks, a mobbed-up union leader. Banks had skipped bail on assault charges in Montreal and disappeared. The FBI and the RCMP couldn’t find him. My father discovered him living on a yacht in Flatbush, Brooklyn. Dad was attacked by four of Banks’s thugs and fled, bleeding, after one of their blackjacks opened the back of his scalp.

Two years later, a headline blared “Star Man Finds Gerda Munsinger”– an East German prostitute and probable Soviet spy who had carried on an affair with Pierre Sevigny, a cabinet minister in the government of John Diefenbaker in the late 1950s. Although she was said to be dead, my father found her very much alive in Munich. When he banged on her door, she thought he was an assassin sent to silence her.

The Reguly family rolled into Chevy Chase, Md., in a banged-up red Volkswagen Beetle with three kids – me and my younger sisters, Susan and Rebecca – and a dachshund named Peanuts. Chevy Chase was a wealthy, all-white neighbourhood of congressmen, lawyers, journalists, lobbyists and doctors. At one hockey game, I looked up and saw Dad absorbed in conversation with Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, the driving force behind the Vietnam War’s escalation between 1965 and 1968, when more than 525,000 U.S. soldiers were stationed in the country.

My father, born in Thunder Bay of Slovak parents, and raised poor, was an immediate sensation in Chevy Chase. He was big – 6-foot-2 – and blind in his left eye, the result of an injury from an arrow when he was a little boy. To fund his university education, he had worked for the Saskatchewan Smoke Jumpers: adventurers, as fit as Navy Seals, who would parachute into forest fires, then walk out.

Outgoing, direct, quick with a joke and considered exotic, he was always dashing off to crazy places and meeting high-powered people. Kim McGettigan, the girl next door who is still a great friend of mine, remembers Bob having an “air of danger about him” that the street wives found irresistible. “Bob was catnip to the ladies of Chevy Chase,” she says, “and it did not go unnoticed by the husbands on the block.”

The war by then had gone from foreign adventure to American existential crisis – the mechanised slaughter of the innocents, as some viewed it, now appearing nightly on prime-time TV. His trip to Vietnam, less than a year after we arrived in Chevy Chase, was inevitable and, for my mother, an exercise in high anxiety.

In an era before the internet or mobile phones, she tracked his whereabouts by reading his stories in the Star, which were delivered from Toronto once a week. Even the Star’s foreign editor didn’t know where he was until his stories landed. Regular phone calls from Edgar Ritchie, who was then Canada’s ambassador to the United States, provided some comfort. Through his intelligence pipeline to Saigon, he could at least assure Mom that Dad was alive.

“I lost 30 pounds,” she says. “I am not exaggerating. I couldn’t sleep. I got depressed. I knew he wasn’t coming back.”

She was saved by her neighbours, the kindest of whom was Kim’s mother, Valerie, a garrulous firecracker of a woman who essentially took charge of all of us when my father was in Vietnam. “Valerie looked after me,” Mom says. “She asked me every day to come to supper.”

The meal was inevitably preceded with a classic Chevy Chase relaxant. “She made a martini for me, put two olives in it, and I just loved it. I had a drink every night.”

Feb. 6, 1968: D.R. Howe treats the wounds of Private First Class D.A. Crum during Operation Hue City. The fighting in Hue, a rare example of street-to-street combat in the Vietnam War, was the model for fighting scenes in the film Full Metal Jacket.NATIONAL ARCHIVES/AFP/Getty Images

Central Vietnam, early February, 2018

After the DMZ, Nhung and I are determined to stick with our plan. We will wind our way south, stopping in as many spots as we can that match my father’s place lines in The Star.

Hue is next. And it is a marvel. The imperial capital from the early 1800s until 1945, it is still dominated by the enormous citadel, its menacing two-metre-thick walls facing the Perfume River.

Tim Page and Don North had warned me that I would find little visible evidence of the war here, and they were right. Forest and farmland have consumed landing zones and air bases; some of the house-sized holes left by B-52 bombers are now duck ponds.

In Hue, though, you can still feel the war.

The Battle of Hue, which was the model for the fighting scenes in Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket, was Second World War-style street-to-street combat. Among the longest battles of the war, it ran from the start of the Tet Offensive, on Jan. 30, 1968, through early March, and pretty much levelled the city. The citadel and what’s left of the imperial palaces are raked with bullet holes; some walls remain unbuilt. Our visit on a leaden, wet day reinforces Hue’s spooky aura.

My father arrived in Hue half a year before the big battle, and his Star stories from here – by turns funny and disturbing – comprise telling vignettes of life during wartime.

In one, he writes of two French priests who drive over a small landmine that wrecks their Jeep, but leaves them only slightly wounded. The next day, the Viet Cong track them down and demand payment for the mine, which was meant for American military vehicles, not civilian Jeeps. “The priests paid. Non-payment meant execution,” my father writes.

In another, he interviews an American pilot who was making a low-level strafing mission over a field when a Viet Cong stood up and hurled rocks at the plane. He quotes the pilot: “I made another pass and let go at him with my rockets and guns. His head went sailing over my canopy.”

Robert, far right, spent time with the Saskatchewan Smoke Jumpers, a firefighting force that leapt into fires at low level. His parachuting experience with the Smoke Jumpers would come in handy in Vietnam, where he flew in a Skyraider.Eric Reguly/The Globe and Mail

U.S. Air Force Captain James Thyng stands in front of his Skyraider, loaded with napalm. In June, 1967, he would take off with Robert Reguly from Pleiku to look for Viet Cong targets.Frames & Thyngs

Pleiku, early February, 2018

The Douglas A-1 Skyraider was a brute of a plane – and already an anachronism by the Vietnam War. In an era of supersonic jets, it employed an 18-cyclinder piston engine, designed in the Second World War, to chop its way through the air.

But it flew low and slow, picking out targets that the jets would miss. The U.S. Air Force and the Navy lost more than 260 Skyraiders in Southeast Asia. It was a widow-maker. Anyone who chose to fly it was, by definition, brave, perhaps stupidly so.

My father would go on a Skyraider mission in June, 1967, out of Pleiku, the main city in the Central Highlands, just east of Cambodia, and home to one of the USAF’s biggest bases – the Ho Chi Minh Trail was nearby. “Anything for a story,” he wrote in his notes to me.

We arrive in Pleiku after a bouncy, eight-hour trip from the coast in a Toyota SUV that takes us along parts of the Ho Chi Minh Trail, past waterfalls, and forests mutilated by illegal logging. My father would fly his Skyraider mission over this rugged landscape.

His plane, which took to the sky alongside another Skyraider, was piloted by one Captain James Thyng, whose personal insignia, a lucky shamrock, was stenciled onto both sides of the camouflaged fuselage. Both men wore parachutes – as a former smokejumper, my father would not have needed a lesson on pulling a rip cord. There were no ejection seats. If they needed to bail out, they would have to climb down onto the wing – and jump.

An oil painting by David Rider shows EC883, the Skyraider plane that Captain James Thyng and Robert Reguly flew in over Pleiku.David Rider

Staying put in the cockpit delivered plenty of drama on its own. Spotting a single thatched hut – could it be an ammunition dump? – Capt. Thyng proceeded to deliver the all-American wipe-out treatment.

My father, writing in the Star: “[O]ur Skyraider plummeted into a 60-degree dive from 5,000 feet, dropped two bombs from 2,000 feet, pulled up sharply at 1,000 feet, the 2700-hp engine clawing for sky ... [We] made four dives, pulling out with a fake left and climbing off to the right. Each plane alternated passes – ‘so the enemy doesn’t know what’s coming next,’ pilot Thyng said in the intercom.”

The two planes then circled around for a strafing that did not produce a secondary explosion; the hut probably had not been hiding ammo. “After the landing back in Pleiku, Capt. Thyng was slightly apologetic over the mission,” Dad’s story reads, “saying they’re often much more interesting.”

Given the high mortality rate among Skyraider pilots, and the 50 years that had passed, I didn’t expect Capt. Thyng to still be standing. But thanks to the internet, I find him in Pittsfield, N.H., his hometown. He is 76 and tells me on the phone that he has a heart problem, but is otherwise well.

Incredibly, he remembers my father. “Your dad was courageous,” he says, a far cry from a particularly nervous Australian journalist he once took aloft: “He carried three canteens, one water, two vodka.”

Capt. Thyng flew 301 missions in 1966 and 1967; his plane got hit 43 times. In one mission, the ground crew counted 288 holes in his Skyraider. In another, he crash-landed at the Pleiku airfield after cannon fire, he says, “blew the belly out of my plane.”

Capt. Thyng was, and remains, a hawk who thinks the Americans lost the war because they didn’t invade North Vietnam; didn’t level Hanoi and Haiphong, the main port and industrial city in North Vietnam; didn’t go on dam-busting raids that could have flooded the rice fields and triggered a food crisis. “I was feeling, what the hell are we doing here if they don’t let us fight the war?” he tells me now.

Nhung and I go to Capt. Thyng’s Pleiku airbase. It’s easy to find. It has been converted into the city’s modern airport – same footprint. We can’t find a trace of the old field, even though it was vast. I am disappointed: I wanted to send a photo of an old reinforced Skyraider hangar or another war relic to Capt. Thyng, who never went back to Vietnam after the war. For all the missions he flew, for all the comrades he lost, there was only defeat, symbolized by the total eradication of the American presence here.

Instead, I send him a photo of me standing in front of a Skyraider at the War Remnants Museum in Saigon and he’s thrilled.

Eric Reguly stands in front of a Skyraider, like the one his father flew in, at the War Remnants Museum in Saigon.Eric Reguly/The Globe and Mail

Plei Beng, early February, 2018

On June 12, 1967, the Star published a story under the headline “Moving day for the Montagnards meant helicopters at gunpoint,” next to a shot of my father in army fatigues. It included two photos taken by him. One is of a Chinook heavy-lift helicopter hovering over the village of Plei Beng; the other shows a young man in a loincloth, with a goat, waiting for the airlift. He looks perplexed.

What my father bore witness to that day was the forced relocation of Montagnard tribespeople in Vietnam’s Central Highlands, southwest of Pleiku,near one of the main branches of the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Montagnard is French for “people of the mountain,” a catchall term that any anthropologist would find meaningless: The Montagnards are composed of many minority ethnic groups, each with its own language and customs.

During the war, the Americans turned millions of Vietnamese into refugees in their own county, moving them into “strategic hamlets” protected (often badly) by U.S. and South Vietnamese troops, and turning their previous homelands into wholesale killing zones under the assumption that anyone who stayed behind was the enemy.

Robert Reguly's Star report on the Montagnards.Eric Reguly/The Globe and Mail

Here are excerpts from Dad’s story that June day:

“The 422 Montagnard villagers scratched themselves awake at dawn to find 150 U.S. infantry men surrounding them ... Then they hunkered down to await the twin-rotored Chinook helicopters that would take them away to the giant resettlement camp 12 miles away ... The idea is to move about 10,000 Montagnards into one massive tin-roofed Levittown guarded by 1,000 Vietnamese troops. This would turn a 400-square-mile area in the Central Highlands into a ‘free fire zone,’ where anything that moves would be regarded as the enemy ... Plei Beng, explained the American officer directing the evacuation, was regarded as a ‘hostile village.’ He said the North Vietnamese came in every eight days to collect rice and cart off a few young men to dig bunkers in the surrounding hills ... At 5 p.m., the last chopper-load whirled aloft, leaving the troops to burn down the village with thermite grenades, gasoline and matches.”

Plei Beng does not exist on any map I find. Did the Montagnards return to the village after the war? I didn’t know – but I did know that I wanted to find the spot where my father had documented its dismantling.

The only clue I find comes from the website of Peter G. Bourne, an expert in combat stress who fought in Vietnam and joined a combat patrol to capture an “enemy village” in the Highlands. His report on that experience, titled The Road to Plei Beng, put the village “northwest of our camp, Duc Co, only a few minutes away by helicopter but nearly 24 hours’ march through the jungle.”

Duc Co we can find: It was a Special Forces camp best known for the 1965 baptism of fire of (Stormin’) Norman Schwartzkopf, the celebrity general in charge of coalition forces in the 1991 Gulf War. We find the old runway, now nothing more than a level expanse of red dirt.

As we drive, Nhung suddenly finds a “Beng” with her maps app. It’s only a few kilometres from Duc Co. That must be it – and it is.

Beng, formerly called Plei Beng, is a rural village surrounded by cashew and rubber trees. It was a challenge for Eric and his interpreter to find it.Eric Reguly/The Globe and Mail

Beng is a hardscrabble hamlet: a couple of dozen simple houses, many with chickens and pigs running around outside, a small general store and, oddly, an outdoor beauty parlour where a young woman – all smiles – is cutting a client’s hair.

Few foreigners come to Beng, in part because it’s a “restricted” area; we’re supposed to have military clearance to be here. We ask if we can talk to the oldest person in the village, and soon meet Roh Cham Chich, who says he was 11 in 1967 and living in a nearby village. He doesn’t recall the helicopters but does remember U.S. trucks running back and forth (probably carrying the Montagnards’ livestock to their new home). “Only half of the Montagnards agreed to [get evacuated],” he tells us. “The ones who didn’t would go to Cambodia and join the North Vietnam forces.”

As our driver urges us to leave before the military shows up asking rude questions, we spot an old man, hunched, moving slowly toward his sturdy little house, which is painted a pleasing light green. He is thin, wears a baseball cap and a brown sweater, and has a gentle, if distant, air about him. His eyes are sad and he speaks ever so softly as his daughter explains that he is not well and has little energy. Bending over to steady himself, he struggles up the three front steps to his house and shuffles to the edge of his wooden bed – no mattress – which faces outdoors.

He is Kpuih Doan, is almost 80, and was in Beng, then known as Plei Beng, during the evacuation. His daughter says he collected scrap metal after the war, no doubt from bombs, which means he was probably exposed to chemicals that could have damaged his brain and nervous system.

I hand him a copy of my father’s story and he looks intently at the photo of the Chinook helicopter hovering over the village – his village. His eyes light up. “Yes, I remember the helicopters like this,” he says softly. “I remember collecting our belongings.”

He gives me a weak smile as he clutches the newspaper story. At that instant, I feel certain that my father saw this man, maybe even met him or photographed him, on that hot, dusty, frightening day in June, 1967.

You are part of my father’s history, I think, and now mine.

Kpuih Doan, a Montagnard villager in Beng who remembers the evacuation and destruction of his village, holds a Robert Reguly newspaper report of the event.Eric Reguly/The Globe and Mail

Saigon, late February, 2018

Looking at the pink dots on my Vietnam map when I get back to the Hotel Majestic, I realize that Nhung and I have visited no more the half of the places my father did as he brought the reality of war home to North American readers.

Among the sites we have had to forgo is Rach Kien, a village about 20 km southwest of Saigon, in the Mekong Delta, where he went aloft in a Bird Dog observation plane – a small, single-engine Cessna. That mission’s purpose was to spot suspected Viet Cong hamlets and mark them with smoke grenades and white-phosphorous rockets, after which the F-100 Super Sabre jets circling overhead would swoop in with high-explosive bombs, napalm and 20mm cannon fire.

One hamlet was eradicated as my father and the Bird Dog pilot, Paul Sullivan, watched the explosions. “Thanks for coming down,” Sullivan told the Super Sabre pilots, one of whom responded: “Rodge. Thank you. We enjoyed it.”

Oh, the casual brutality of war.

As I review Dad’s stories, and the 1,000-word note he left me, I find no published reference to what probably was his most dangerous mission: He actually went behind known North Vietnamese Army lines on a long-range reconnaissance patrol, or LRRP (pronounced lurp), with a small group of Marines. The LRRP soldiers were stealth fighters who sometimes had to engage in hand-to-hand combat. Absolutely bonkers, I think – did he have a death wish?

This particular LRRP’s mission was to find NVA tunnels and mark them for air strikes. “The price to join the four-man lurp is to carry an M-16 rifle and four fragmentation grenades,” his note says – in what would be his last written words to me. “A specially muffled Huey drops us. There is no smoking, no talking, just hand signals ... One soldier strips and crawls inside [the tunnel]. Yep, this is the place. We slip back to an open spot, ignite an orange flare and, as the chopper comes in, we lace the shrubbery with gunfire, for a chopper is most vulnerable when it is descending. The big risk: A newsman armed is summarily shot if caught.”

For all the drama of Dad’s time in the field of combat, the newspaper stories that leave the deepest impression on me are the ones he wrote near the end of his Vietnam stay, in late July, 1967, as the war was getting more intense by the day. In essence, they portray the “American war,” as the Vietnamese call it, as a colossal mistake.

At the time, my father’s was a minority view. Even as thousands of U.S. troops were returning home in body bags, most Americans continued to buy the argument that Vietnam was a “domino” whose fall would enable communism to spread unchecked.

In one article, he says that the Americans were making endless enemies through village “resettlement programs” such as the one he witnessed at Plei Beng. “The refugee population is swelling at an astounding rate all over Vietnam,” he writes. “It may also be creating more [Viet Cong].”

And there is this, from an article entitled “Viet Nam peasants are the losers in ‘the other war’ ”:

“The marines have an operation called ‘country fairs.’ They will surround a village before dawn, summon the inhabitants for some medical treatment, free teeth-pulling, music, candy for the kids – and propaganda. The marines go into the village and exterminate those who have not joined the congregation, on the assumption those who stayed are VC.”

In yet another article, he questions Washington’s optimism for victory, explaining that the American measure of success is the body count and the kill ratio – the (relatively small) number of U.S. soldiers dead compared to the (relatively high number) of Viet Cong and NVA killed. These numbers are “recounted daily in the Saigon press briefings like football scores,” he writes, adding that the number of enemy troops allegedly killed is “sometimes preposterous.”

He also notes the “notorious reluctance” of the South Vietnamese army to go into battle, the “endemic corruption” of the Saigon government, and the ever-more deadly weapons used by the NVA.

His conclusion: “The war can only be won by the Vietnamese; but it can be lost by the Americans.”

It was a conclusion that time would justify. On April 30, 1975, a North Vietnamese T-54 tank smashed through the gates of the presidential palace in Saigon, ending the war and the 15-year American presence in Vietnam. By then, Dad was, unhappily, back in staid, dull Toronto after having covered the American war protests and race riots (for which he won another National Newspaper Award), the assassinations of Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King, the 1968 election of Richard Nixon, the Apollo moon shot, and, later, from his new Toronto Star base in Rome, the Biafran war, the Indo-Pakistani war and the Arab-Israeli conflicts in the Middle East.

He had a sensational run. But no story riveted Dad like Vietnam. To him, the war was the ultimate thrill, the ultimate reporting challenge. But he also saw it for what it was: the ultimate American travesty, and a tragedy for millions of Vietnamese.

To this day, I am envious of Dad’s Vietnam assignment – I never have and never will get one like it. I am so proud of him for what he accomplished there. Following in his footsteps gave me a new level of respect not only for his sheer daring as a journalist – most of his bylines came from the field, not from the safety of Saigon – but for the humanity, intelligence and foresight that infused his writing.

No, he was never a great father. He was always away. When he was home, he was away too, obsessed with the next big story, buried in newspapers, drinking with contacts, largely oblivious to the needs of his stressed-out wife and three young kids.

For that, I forgive him. Call it hero worship. Because a hero he was, to me.

Robert Reguly in the Toronto Star newsroom in March, 1966.

The returned: Two stories of Americans who went back to Vietnam to do good

by Eric Reguly

At the height of the Vietnam War, in 1968 and 1969, more than 525,000 American troops were stationed in Vietnam. Throughout the entire “American” war – 1964 to 1973 – some 2.7-million Americans served in Vietnam. Thousands of them have returned as tourists. A very small number went back and stayed, partly out of guilt. They were appalled by the destruction inflicted on North and South Vietnam during the war and wanted to do their small part to help repair a country they would come to love. Here are the stories of two of them, both of whom I met during my Vietnam trip.

Ray Wilkinson in 1968, just outside Khe Sanh, site of one of the biggest battles of the war.Handout

Ray Wilkinson

As a marine, Wilkinson, now 74, had an unusual double role as soldier and reporter. Born in England, he arrived in Vietnam in 1967, and, a year later, fought in, and covered, two of the longest battles of the war: Hue and Khe Sanh. He was writing for both the Stars and Stripes, the U.S. military’s daily newspaper, and Leatherneck, the Marines’ magazine.

After the war, he became a civilian reporter for UPI and Newsweek, covering endless conflicts – 26 in total, by his count – in Africa and the Middle East. (In the early 1970s he was based in Cairo and probably met my father, who, at the time, was covering the Middle East for The Toronto Star.) He would also have long stints as a spokesman for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and as a consultant for the Japanese International Co-operation Agency.

Ray Wilkinson, now 70, lives in Dong Ha, Vietnam, and teaches English.Eric Reguly/The Globe and Mail

Four years ago, retired and restless, he was offered an unpaid teaching position in Dong Ha, in the northern part of what was South Vietnam, by an American charity. Wilkinson couldn’t believe it – he had spent a lot of time in Dong Ha during the war, when the small coastal city was home to a big Marine base. Today, he lives in a hotel in Dong Ha, teaches English at the local Le Quy Don School for gifted students – and loves it, in spite of occasional visa problems.

“I have been to Vietnam as a marine, as a foreign correspondent, as a UN refugee official, as a development consultant and now as a teacher,” he says. “It feels good to help these kids. Some wars were necessary. The Vietnam war was totally unnecessary.”

Through the charity organization Project RENEW, Chuck Searcy has helped to save lives in Vietnam by clearing unexploded ordnance left over from the war.HOANG DINH NAM/AFP/Getty Images

Chuck Searcy

When I was traipsing around the former demilitarized zone, looking for the site of the 1967 battle that trapped my father in a foxhole for three days, I was warned not to stray from marked paths, because of all the unexploded ordnance – UXO. Since the war’s end in 1975, more than 100,000 Vietnamese have been killed or injured by UXOs. But every year, the number of casualties falls, thanks in good part to Chuck Searcy, who in 2001 helped to start Project RENEW, a Vietnamese and international charity that cleans up UXOs in Quang Tri Province in central Vietnam (where the DMZ was located); it is one of the most heavily bombed and mined spots on the planet.

Mr. Searcy, 73, was an intelligence specialist in the U.S. Army in 1967 and 1968 and became an anti-war activist after going back to his home state of Georgia. Later, he became a muckraking newspaper publisher. He returned to Vietnam in 1995 as a member of the Vietnam Veterans of America Foundation, and got Project RENEW going from his base in Hanoi. The charity is expanding and is helping the victims of Agent Orange, the dangerous defoliant that the Americans sprayed over much of South Vietnam, leaving one million or more Vietnamese with severe health problems, including deformities.

“Vietnam was in very bad shape when I first visited after the war,” he says. “I thought, maybe I should come back and do something helpful for this poor place. There’s still so much left to do.”

Eric Reguly

Eric Reguly