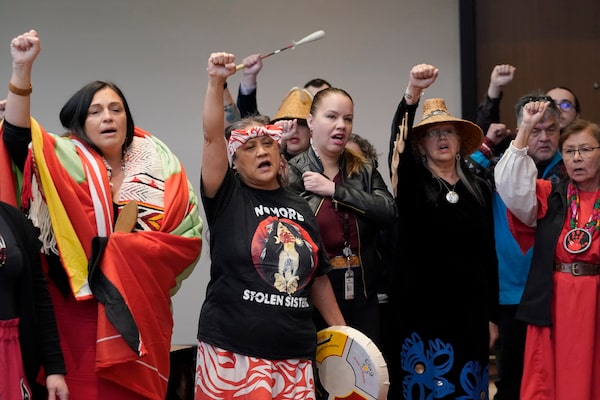

Monie Ordonia, second from left, of the Tulalip Indian Tribe, joins others in singing an honour song after Washington Gov. Jay Inslee signed a bill that creates a first-in-the-nation statewide alert system for missing Indigenous people, on March 31, 2022, in Quil Ceda Village, near Marysville, Wash.Ted S. Warren/The Associated Press

A pioneering alert system for missing Indigenous people has brought new attention to a group that has historically felt ignored by authorities, part of a broad reckoning that is remaking Washington state’s relationship with tribal communities.

It is a change that is beginning to extend its reach. Other states are now replicating the new alert system, which advocates say Canada, too, should consider.

But its creation has also brought to light fresh problems, as authorities struggle to raise awareness among local police about the new tool and work with neighbouring states to find those who are vulnerable.

It’s a bit like a baby taking its first steps, says Debra Lekanoff, a Democratic state representative who is a member of the Tlingit tribe and supported the creation of the new system. It recently completed its first half year in operation.

“We teeter totter. We fall down. And we pick ourselves up, dust ourselves off,” she said in an interview.

The system, which gives police the ability to quickly send out information without having to meet the strict criteria for Amber alerts, has been criticized for failing to act on some cases, while its advocates have struggled to persuade some local authorities to participate. It has exposed limitations in how police departments can work together across state lines to track the missing, and claims only modest results in helping to find missing persons: Out of 43 alerts, all but five people were located – but only four who authorities attribute directly to the system.

Some have questioned its effectiveness, saying they have seen more success with missing-person flyers.

But Washington’s missing Indigenous person alerts have also reoriented the mechanisms of law enforcement to respond with new urgency to cases that once languished. Before the alert system went live on July 1, 2022, it could take multiple days to notify authorities of a missing Indigenous person.

“When the first alert went out, we were able to accomplish that process in less than 30 minutes,” said Annie Forsman-Adams, a policy analyst at the Washington State Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and People Task Force.

“Those first couple of alerts, we found people very, very quickly,” she said.

“So I think it’s really a tool that is useful in doing what it needs to do.”

Indigenous women turn to TikTok to keep spotlight on unsolved missing, murder cases

The idea is spreading quickly. In January, Colorado and California introduced their own systems, which California has called a “Feather alert.” Authorities in New Mexico, Michigan and Minnesota have also shown interest.

In Washington, the alerts form part of a broader attempt by lawmakers and advocates to pry open the eyes of authorities to long-standing injustices. The Washington State Patrol now maintains a list of missing Indigenous people, which it releases every two weeks. The task force created in 2021 has recommended new ways for authorities to collaborate in the interest of serving Indigenous communities.

“We have brought awareness,” Representative Lekanoff said.

Underpinning the alert system is an important change in mindset, with the state deciding to treat a missing Indigenous person as a missing endangered person.

For an Indigenous woman in the state, there is a new sense of security in knowing that if she goes missing, “the person at the grocery store is looking for me, the coach for the NFL Seahawks is looking for me. Everyone is looking for me,” Ms. Lekanoff said.

The Washington State Patrol credits Canada, in part, with bringing the issue of murdered and missing Indigenous people to the fore of national attention.

But the state’s ambitious response to the issue has also cast a critical new light on Canada, where the most comprehensive national database of missing Indigenous people is Aboriginal Alert, a website run by Dan Martel, a Métis consultant in Edmonton. His shoestring budget is supported primarily by his own business, with some additional funding from the province of Alberta. His most effective alerts are boosted posts on Facebook, which he buys for $5 at a time.

It’s far different from the state policing resources dedicated to the Washington alert system.

“There’s more coming out of Washington than I’ve seen in Canada,” he says.

Carri Gordon is at the heart of that effort. The missing person alert co-ordinator for the Washington State Patrol, she has worked with Amber alerts since 2004. Alerting the public to missing Indigenous people has required rethinking how public warnings are issued, she said. Police are often accustomed to working with Amber alerts, which require a known abduction and a reasonable belief that the person cannot return to safety without assistance.

“With the Indigenous alerts, a lot of times, there’s no immediacy to them,” she said.

It is a unique alert.

“The only requirement is the racial demographic,” said Patti Gosch, a tribal liaison for the Washington State Patrol. The alert can only be activated by a request from law enforcement, and that can be slow in coming. At 3 p.m. on the day before Ms. Gordon spoke with The Globe and Mail, an eight-year-old Indigenous child went missing.

“We didn’t get a call for the alert until midnight. That’s not okay,” she said.

Other frustrations have also emerged. Police in Las Vegas, for example, don’t use the National Crime Information Center, a centralized index of fugitives and missing people. That has made it difficult to track Indigenous people who have gone missing there.

In Washington, meanwhile, the state police have been reluctant to use cellphone alerts when Indigenous people go missing, wary of breeding public inattention by overusing the system. But that has limited its reach. “I don’t know how well it’s working, because I haven’t seen those notifications coming through,” said Teri Gobin, who chairs the Tulalip Tribes board of directors.

Chris Sutter, Chief of the Tulalip Police, has found local networks more effective. “We create our own missing person flyers and send that to our community through our tribal social-media person,” he said. “And that tends to get a lot more feedback and tips.”

The alert system has nonetheless yielded tangible successes. A friend told Ms. Lekanoff about seeing a green minivan on a remote road shortly after passing road-alert signs describing a missing Indigenous person in a vehicle of that description. The friend reported the vehicle and the person was located. The broader state focus on missing Indigenous persons has resolved very old cases, too. One person was located 57 years after being reported missing.

“The crux of what we’re doing is giving families closure, if and where we can,” said Ms. Gosch.

The state attorney-general’s office plans to create a cold case unit this year dedicated to missing Indigenous people, and other attempts to redress marginalization of Indigenous people in law enforcement are under way. New procedures will see tribal police train at the same academy as other officers, allowing them to enforce state law off-reservation. (In some other states, the disconnect is so great that tribal police who drive their vehicle off-reservation can be arrested for impersonating an officer.)

“We’re learning a lot that we didn’t know before. Because cops in general weren’t paying attention, I don’t think,” said Ms. Gordon.

In Canada, meanwhile, the RCMP says it is not responsible for creating new types of alerts, saying that falls to provinces and territories. “The decision to institute a new public alert for a specific group is not made by the RCMP,” Corporal Kim Chamberland, a spokeswoman, said in a statement.

Mr. Martel, the founder of Aboriginal Alert in Canada, doesn’t see police alerts for missing Indigenous people as a panacea. But he would nonetheless like to see Canadian authorities take the idea more seriously, in combination with the work he is already doing – which could also benefit from more provincial funding.

“You guys do the alert system,” he said of government. “Get the signs up. We’ll get the moccasin telegraph going. And we will resolve this.”

Nathan VanderKlippe

Nathan VanderKlippe