Votes are counted during a caucus to choose a Republican presidential candidate, at Fellows Elementary School, in Ames, Iowa, on Jan. 15,CHENEY ORR/Reuters

Donald Trump has won a thundering victory in Iowa, steamrolling opponents in the first contest of the Republican nominating process and raising the possibility he could soon have the race for the party’s 2024 presidential nod sewn up.

Voters braved -20 C conditions and icy roads to give the former president about 51 per cent of the vote Monday evening, far ahead of Florida Governor Ron DeSantis and Nikki Haley, the former South Carolina governor and UN ambassador, who finished with 21 per cent and 19 per cent, respectively. Entrepreneur Vivek Ramaswamy trailed in single digits.

Mr. Trump’s record-breaking margin reinforces his dominance of the Republican Party and may squeeze the others out of the race as they struggle to raise enough money to continue. The action now moves on to New Hampshire, which votes next week, followed by Nevada and South Carolina next month.

“This is really time for everybody, for our country, to come together,” Mr. Trump told supporters in Des Moines, the state’s capital and only big city, before uncharacteristically congratulating Mr. DeSantis, Ms. Haley and Mr. Ramaswamy on their campaigns. “They’re all very smart people, very capable people.”

Republican presidential candidate and former U.S. President Donald Trump speaks as he visits a caucus site at Horizon Event Center in Clive, Iowa, on Jan. 15.SERGIO FLORES/Reuters

In his caucus night speech, Mr. DeSantis declared he’d got his “ticket punched out of Iowa” and vowed to continue in the race. “I will not let you down,” he said.

Ms. Haley, meanwhile, pointed to her significant polling leads over Mr. DeSantis in New Hampshire and South Carolina to paint herself as the only viable challenger to Mr. Trump. She characterized Mr. Trump and Democratic President Joe Biden as a pair of unpopular old men whose time had passed.

“I have made this Republican primary a two-person race,” she said as results rolled in. “Our campaign is the last, best hope of stopping the Trump-Biden nightmare.”

Mr. Ramaswamy, who campaigned on outlandish promises such as building a wall on the Canadian border and embraced the white nationalist great replacement conspiracy theory, ended his campaign and endorsed Mr. Trump.

Analysis: Trump’s domination in Iowa raises question about whether Haley vs. DeSantis even matters

Despite intensive campaigning and some US$300-million in advertising spending in Iowa, the end result resembled polling averages from months ago, suggesting voters had already largely made up their minds about Mr. Trump. Several high-profile candidates even abandoned the race before the vote.

A state of 3.2 million best known for its insurance and agriculture industries, Iowa was battered over the week before the vote by a string of blizzards that curtailed campaigning. Its caucus voting format, which requires everyone to cast ballots at in-person meetings, also further pushed down turnout amid the coldest caucus night in history.

While Mr. Trump’s competitors engaged in the traditional town-hall campaigning style Iowa is famous for, the former president stuck to his preferred format of large rallies. He also missed much campaign time to attend legal proceedings in New York and Washington. It was a possible preview of the coming year, as he faces 91 criminal charges across four trials for trying to overturn the 2020 election, absconding with classified documents and falsifying business records.

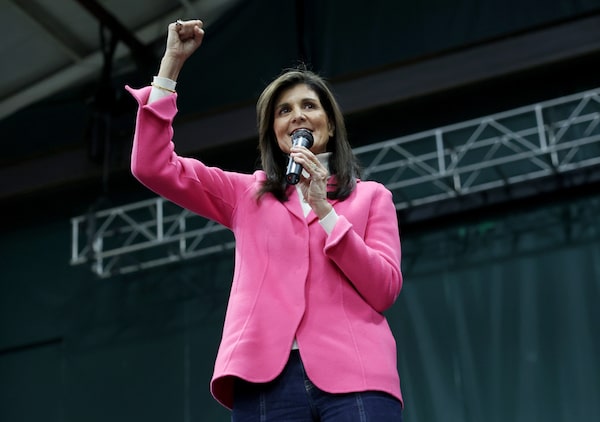

Republican presidential candidate former U.N. Ambassador Nikki Haley speaks to voters a a caucus site at Franklin Junior High on Jan. 15, in Des Moines, Iowa.Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images

Republican presidential candidate Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis speaks during a campaign event in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, on Jan. 15.Nick Rohlman/The Associated Press

None of that, however, seemed to matter much. Many of his supporters believe conspiratorial claims that the Democrats rigged the election, staged the Jan. 6, 2021, riot at the Capitol and framed Mr. Trump for it.

“That was the only way they could win, if they came up with the charges,” said Kristine Baldwin, a real estate broker, as she sat in the audience of a Trump campaign event at a Baptist church in Marion, Iowa, a few days before the vote.

Ms. Haley is the de facto candidate of the Republican establishment, staking out positions – pro-big business, pro-military aid to Ukraine – that contrast with the nationalistic bent of Mr. Trump and Mr. DeSantis.

She will be hoping for a better result in New Hampshire, a more moderate state where Democratic and independent voters may cross party lines to support her against Mr. Trump. Her aim is for an upset result next week, which gives her enough momentum to stay in the hunt until larger, more diverse states vote later in the process.

Sitting in the audience at one of her rallies, Jody Strand mulled whether he could support Mr. Trump if Ms. Haley didn’t get the nomination. His priority in the election, he said, was getting rid of the Biden administration, which he blamed for the high inflation of recent years.

“We need change, anything but what we’re doing right now, to get the country back to work,” Mr. Strand, 61, said. “I don’t think anyone likes Trump but they all liked the economy.”

Mr. DeSantis had high hopes of winning Iowa, where he bet that his culture warrior reputation would appeal to the large voting bloc of Christian evangelicals. Mr. DeSantis banned discussions of LGBTQ issues and structural racism in Florida schools. He also sold himself as aligned with Mr. Trump on policy but more competent at carrying it out.

At a campaign rally in Ankeny, an affluent suburb of the state capital, Des Moines, the night before the vote, Mr. DeSantis excoriated the former president for failing to implement a string of 2016 campaign promises: building a border wall and making Mexico pay for it; stripping citizenship from the U.S.-born children of undocumented migrants; and paying down government debt.

“He did not deliver,” Mr. DeSantis said. “That’s not draining the swamp, that’s filling the swamp.”

Ken Wilson, a 69-year-old retired financial adviser, said he liked Mr. DeSantis’s action on “cultural issues” and effectiveness at getting things done.

“He has proven the ability to lead. When he says he’ll be ready on Day One, I really believe that,” Mr. Wilson said as he stood in the crowd at the Ankeny rally. “I voted for Trump twice but he never had that in place. It was chaos. We don’t need any more of that.”

The rally had an ominous sign for Mr. DeSantis: Most of the audience was filled with the candidate’s out-of-state staffers and volunteers, along with a phalanx of national political reporters, underscoring his difficulty in winning over Iowans.

To many of those staying loyal to Mr. Trump, his personality is just as important as his politics. His unfiltered style, they said, along with his decision to get into politics when he could have retired as a wealthy TV host, convinced them of his authenticity.

“Nobody owns him,” said Roger West, 53, as he covered his ears with his hands against -27 temperatures in a lineup outside a Trump rally in Indianola, Iowa, the day before the vote. “I trust him.”

Adrian Morrow

Adrian Morrow