Workers complete renovations on Massey Hall in Toronto on the eve of its grand re-opening, on Nov. 24.Christopher Katsarov/The Globe and Mail

Massey Hall has never really worked. And yet it has worked magic. Since the concert hall opened in 1894, it’s hosted lectures, chamber music, the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, one of the great jazz concerts of all time and homegrown rapper Shad – all without an elevator or a proper backstage.

After a three-year, $184-million renovation and expansion (plans for which began a decade ago), the hall reopens tonight with a string of concerts by – naturally – Gordon Lightfoot. Mr. Lightfoot is the place’s unofficial mayor, and when media toured the building Wednesday, his Fender amp rested on the stage’s worn floorboards.

Will he notice a difference? If so, it will be subtle. The renovation project, led by Marianne McKenna and KPMB Architects, Goldsmith Borgal Architects and theatre consultancy Charcoalblue, is an extremely subtle affair. The project’s motto, Ms. McKenna said, was a paradox: “Improve everything. Change nothing.”

The Massey Hall renovations are finally done. See the new changes to the iconic Toronto music hall

The top 10 most significant concerts in Massey Hall’s history, as reviewed by The Globe

That’s the right attitude with which to approach a national historic site. From centre stage, the 2800-seat hall looks the same as ever: wooden orchestra seats with red upholstery, two balconies with some filigree and then a ceiling decorated with Moorish arches. The newly uncovered stained-glass windows glimmer. All this is basically the way architect Sidney Badgley, working for the Methodist millionaire Hart Massey, imagined it in the 1890s.

But the sameness is an illusion. All the seats are new, and a set of robots can drive under the floor to pull the orchestra seats under the stage to create a general-admission standing area. The edges of the floor now have a terrace of seats accessed by a level and fully accessible passageway, cooked up by Charcoalblue.

Further up, the balcony has grown in area; and up top, the arches of the ceiling have all been pulled down, rebuilt and reapplied. The ceiling now conceals many tons of steel structure, enough to support a serious PA system and lighting, and an attic space for production. Acoustician Bob Essert said the sound of the hall will be much the same, but not quite: Certain surfaces facing the stage now have a coating of sound-absorbing plaster that should mute some of the awkward echoes that performers used to experience.

The hall now has a dream logic. Climb up into the balconies, mounting the steep rake and ducking past the gold-painted steel columns, and you feel as affably cramped as ever. Then you open a big swinging door and another world – like an extra wing unpacked from your subconscious – reveals itself. This is one of four glassed-in corridors, or “passerelles,” that hang on the outside of the old building. They link the seating sections with the new lobby and bar areas at the other end of the complex, within a new addition.

Here you get up close with the Ionic columns and Don Valley-sourced red brick of the original building; walk around to the back of the hall and you’ll find the new lobby and bar, with sleek white oak, blackened steel and accessible washrooms. “We’re trying to dissolve any sense of enclosure, and open it up to the city,” Ms. McKenna said.

A section of Massey Hall in Toronto protrudes out the building and is encased in glass, photographed on the eve of its grand re-opening, on Wednesday, November 24, 2021. (Christopher Katsarov/The Globe and Mail)Christopher Katsarov/The Globe and Mail

The biggest changes are behind the stage. Here, KPMB (including principal Chris Couse and associate Graham Baxter) designed a seven-floor addition that contains all the nuts and bolts that Massey had been missing, including a loading dock. The whole complex is now called Allied Music Centre.

The addition includes two new venues – a 100-seat theatre and a 500-seat club-style space with a stage whose backdrop is a picture window overlooking Old City Hall (another important Toronto building of the staid 1890s, waiting for its own restoration.)

While those new venues won’t be done until next year – electricians and millwork contractors are still at work at the moment – they will transform the hall’s role in the city, providing smaller streaming-ready venues for developing artists. “Across the city, venues are disappearing,” said Jesse Kumagai, CEO of Massey Hall and Roy Thomson Hall. “We’re hoping that artists will start performing in these spaces, and make their way to Massey Hall.”

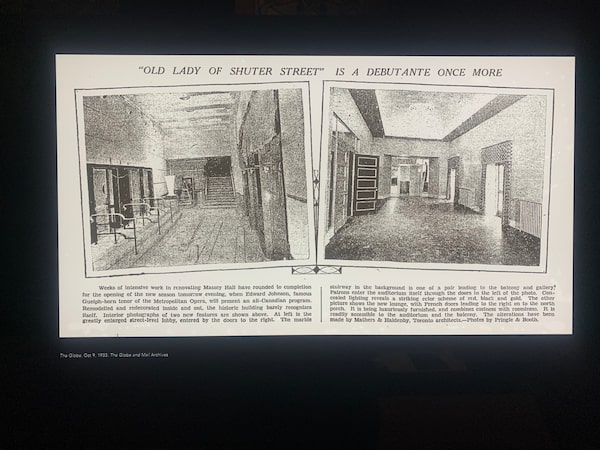

This article from The Globe and Mail, circa Oct. 9, 1933 is on display at Massey Hall.Alex Bozikovic/The Globe and Mail

The new architecture is quiet and serious, as one would expect from KPMB and Ms. McKenna in particular – an expert in theatre architecture who oversaw the renovation of what is now Koerner Hall at the Royal Conservatory of Music.

The architects have allowed themselves a few beautiful details – new pearly terrazzo on the stairs, and a “curtain” of bias-cut red brick that slides onto the old facades – but these are few. “The emphasis at Massey was all on the hall itself, and on bringing people together,” Ms. McKenna said. “Music does that: It creates community.”

The new version of Massey Hall is only the latest in a string of changes. The first iteration combined that flashy Moorish detail on the interior (en vogue in the 1890s) with a very severe neoclassical exterior. Later additions of the 1930s and 1940s added an art-deco character in the revamped stairs and lobby, and tacked on fire escapes out front.

All of this remains, cleaned up – inscrutably altered, but the same in spirit. And the payoff is clear from the main entrance on Shuter Street. Look twice: The steel fire escapes are gone. The sandstone and brick façade is, for the first time since the 1930s, plain to see. It’s very Victorian, very serious – very much the product of a colonial city suspicious of music and secular fun. But the distinctive red neon sign is back, too. The lights are on once again.

Sign up for The Globe’s arts and lifestyle newsletters for more news, columns and advice in your inbox.

Alex Bozikovic

Alex Bozikovic