The past 12 months were an extraordinary year for Canadian culture. While cinemas, theatres, concert halls, galleries, museums, and even book stores were off-limits, the arts themselves never went away. Indeed, this country’s most passionate and dedicated voices only grew louder, finding all kinds of ways to remind us about the power of creativity, and the importance of meaningful cultural change. Here, The Globe and Mail spotlights a handful of these heroes of Canadian arts who made 2020 such an exciting and invigorating year, despite absolutely everything else.

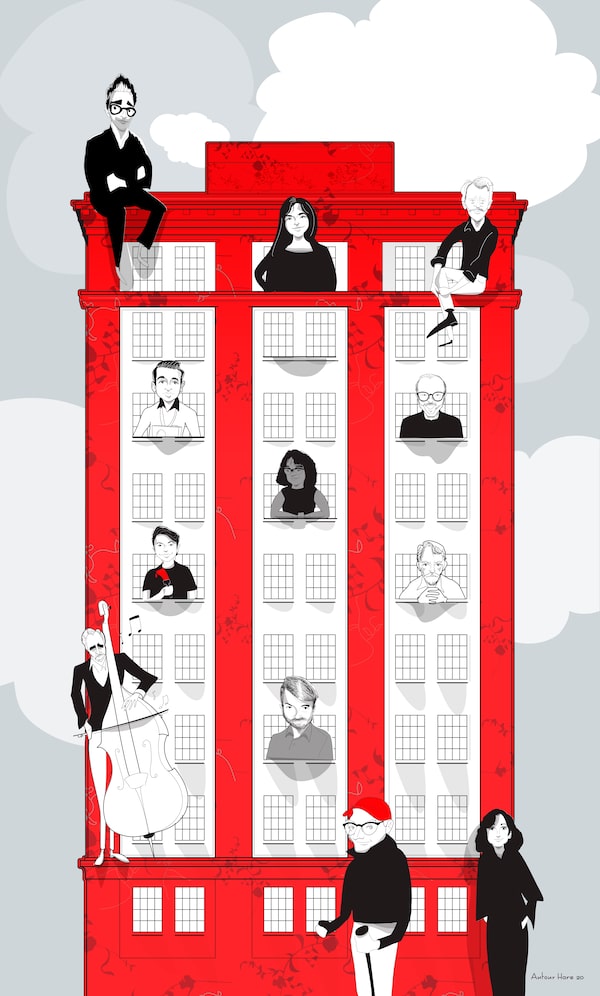

Illustrations by Antony Hare

The Archipelago artists at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Toronto: Leeay Aikawa, Stephanie Bellefleur, Tania Costa, Lily Huang, Wenting Li, Vanessa Maltese, Erin McCluskey, Val Sears, Yen Linh Thai, Kelcy Timmons and Jinke Wang

Squatting on the floor, their faces masked but their brushes busy, they worked for more than 1,500 hours to execute one giant paint-by-numbers project. The 11 local artists hired to create the colourful floral patterns designed by the Taiwanese artist Michael Lin for Toronto’s Museum of Contemporary Art are just the latest example of studio assistants wielding the actual brush. But this time, the master could never put in an appearance. Instead the team that created Archipelago, a series of floor paintings and low seating platforms in the MOCA lobby, were directed remotely from Lin’s Paris studio. Toronto team leader Vanessa Maltese (shown in the illustration above) would give studio director Isabelle Georges daily tours on her phone.

The group, hired for their experience on mural projects and their clean, graphic painting style, were provided with giant mylar printouts of Lin’s design that they stencilled onto the floor using transfer paper. The artist had selected colours from paint chips and Maltese then drew up a legend, checking back with Paris to make sure the actual floor paints were matching Lin’s original choices. Then they got to work.

“It was quite physically demanding. We had to be in a frog position on the floor,” Maltese said, adding, “It was amazing to see it come together.”

The artists were paid by the hour and MOCA staff also provided mentorship with a series of lectures and workshops about the art world and museum practice. The completed Archipelago was only open to the public for one weekend before MOCA was forced to close, but some visitors saw it during installation. The children were the best audience, Maltese said; sometimes they disputed Lin’s colour choices, suggesting more pink. –Kate Taylor

Yolanda Bonnell

Theatre artists having concerns about theatre criticism is nothing new. But, in February, Yolanda Bonnell, an Ojibwe and South Asian performer and playwright, decided to directly challenge “current colonial reviewing practices” by inviting critiques from IBPOC [Indigenous, Black and People of Colour] writers only during the remount of her Dora-nominated play bug at Toronto’s Theatre Passe Muraille.

Bonnell’s selective invitation provided fuel for theatre journalists to opine on race and reviewing not just in Canadian media – but as far afield as The Guardian in Britain, El Pais in Spain and L’Obs in France. The old theatrical saying “any publicity is good publicity” was not coined by an Indigenous woman, however; Bonnell says this was a traumatizing time as she was targeted with hateful messages and death threats.

Nevertheless, Bonnell and bug also sparked or revived quieter conversations in newsrooms about a paucity of IBPOC theatre critics. And her ask hardly seemed radical at all when summer came around and George Floyd’s killing by police led to a wider societal racial reckoning. An American group called We See You White American Theater released a full list of demands rather than requests about criticism – including that producers not buy ad space in the New York Times, the L.A, Times and the Washington Post until they had 50 per cent IBPOC critics. Its hundreds of signatories included Lin-Manuel Miranda, Sandra Oh and Sterling K. Brown. Bonnell went out on a limb ahead of them. –J. Kelly Nestruck

Edward Burtynsky and Nicholas Metivier Gallery

In the early days of the pandemic, Canadian photographer Edward Burtynksy found himself isolated in Ontario’s Grey County when he was supposed to be flying off to Africa. He decided to put the sudden gap in his schedule to good use, got out a digital camera and started experimenting.

Burtynsky is known for his giant images of industrial landscapes shot around the world but now he began touring his own backyard just as spring was emerging in the Ontario woods. Using technology that can stack multiple exposures to create a single image, he was able to achieve a range of detail and depth of focus that previous photographs couldn’t match.

He showed the results at the Nicholas Metivier Gallery in Toronto in September and, seen as large-scale prints, the photographs proved oddly unsettling. The viewer’s eye is so accustomed to the shallow depth of field of a traditional photograph – foreground sharp; background fuzzy – that there seemed to an aura of the inexplicable or unnatural about these hyper-focused images. In truth, they reproduce something closer to the way the eye actually sees the world as it darts about bringing different bits of a view into focus.

Burtynsky and the Metivier Gallery are donating $200,000 from the sale of the Natural Order – Grey County series to photography acquisition funds at the AGO and the Ryerson University Image Centre to buy the work of emerging and mid-career Canadian artists. –Kate Taylor

Wesley Colford and Arkady Spivak

The groundbreaking Canadian director John Palmer died this year of COVID-19 – reviving memories of the glory days of Toronto Free Theatre, a company he co-founded in 1972 that, indeed, had free admission in its early days. But the idea that theatre should be free was also reborn during this pandemic. And leaders at two Canadian theatre companies acted immediately on “building back better” by removing financial barriers to their essential services.

A six-year-old company in Sydney, N.S., the Highland Arts Theatre (HAT) is what executive director Wesley Colford calls an “emerging professional” theatre.

Without any operating funding, Colford and the HAT team quickly sprang into action with a plan on how to replace the threatened loss of $600,000 in box-office revenue by starting a “Radical Access” campaign. The idea: Find 2,000 people in the community to sign up for monthly donations of $25 ($300 a year). When that goal was met, ticket prices were eliminated for all.

In Barrie, Ont., Talk is Free Theatre (TIFT) just cut to the chase – announcing it would provide free admission to all core theatre programming for three years.

Artistic director Arkady Spivak has always structured TIFT so he doesn’t have to worry about box-office revenue and can program eclectically; last season, box office was just $60,000 on a budget of $1,070,000.

“It’s just not worth it to keep it as a barrier for so many people,” Spivak says. “It’s easy to give it up and replace by strategic fundraising instead.” –J. Kelly Nestruck

Mark Haney

Mark Haney is a composer, double-bassist and managing artistic director of Vancouver’s Little Chamber Music. In March, he also became a musical matchmaker. Knowing musicians would be among the hardest hit, with gigs abruptly cancelled – and realizing arts patrons suddenly had no events to buy tickets for, he dreamed up the Isolation Commissions. For $200, a patron could commission a short video and choose the musician, genre, instrument – or leave it to Haney. He figured he’d broker maybe 25 pieces. By June, when the program wound down, 130 videos had been commissioned, raising nearly $30,000 – all of which went to the musicians.

Among the patrons was a Burnaby high school teacher. Distressed that she could not be with her students as they prepared for exams, she commissioned a motivating five-trumpet video of Mark D’Angelo playing the theme from Superman. This year, Haney also COVID-altered two major events. On the 75th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima, he brought together a masked orchestra at the Polygon Gallery to play a program that included Krysztof Penderecki’s Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima for an in-person audience of two: a survivor of the bombing and her husband. For Remembrance Day, he planned to have 75 female voices perform a 40-minute meditative piece at a Vancouver cemetery, representing 75 enlisted Canadian women who died during their Second World War service. Instead, he streamed a shorter piece.

There were also small pop-up performances in the cemetery – including one near the graves of two of the women. Haney’s work brings to mind the Christopher Reeve quote that teacher used at the end of her Isolation Commission: “A hero is an ordinary individual who finds the strength to persevere and endure in spite of overwhelming obstacles.” –Marsha Lederman

Joel Ivany

In answer to the challenge presented to performing arts organization this year, we saw some regrettable poverty of imagination and ingenuity. Not so with Against the Grain Theatre (AtG), the small but indomitable opera company. To its great credit, in its 10 years alive, AtG has been devoted to opera in unconventional spaces with unique approaches. It has also relied on social media to build an audience for everything from its Dora-winning productions to its popular Opera Pub Nights.

Founder and artistic director Joel Ivany nimbly moved AtG online, created a YouTube channel and weekly, if not more often, presented performances, discussions with performers and directors and then created original digital content. First there is the unique web series A Little Too Cozy, “a digital prequel” to the company’s inventive, re-imagined version of Mozart’s Cosi fan tutte as a TV dating show. The original production was done at CBC studios in 2016. Ivany turned TV writer/director for a backstory to that crazy reality-TV/Mozart mash-up. Fresh and cheeky, it’s about the contestants and the makers of an absurd TV show about love and ego

Then came the ingenious and stirring Messiah/Complex, an online performance interpretation of Handel’s Messiah using 6 languages, 12 soloists, four choirs, and anchored in the Toronto Symphony Orchestra. The 70-minute filmed performance is truly an inclusive Canadian experience, in Arabic, Dene, English, French, Inuktitut, and Southern Tutchone. With singers participating from every province and territory, and the whole country in vivid display, the work is an astonishing declaration of optimism when all around is COVID-induced doom and gloom. –John Doyle

Beth Janson

No one would have blamed the Academy of Canadian Cinema and Television if it just took 2020 off. Or at least stayed in a holding pattern. Yet, the Academy’s CEO Beth Janson decided to look an industry-shaking crisis in the eye and say, basically, to hell with that.

Thanks to Janson and her team’s drive and commitment to meaningful change, the Academy has spent the pandemic rolling out a series of initiatives to ensure that the Canadian arts’ newfound attention to the all-encompassing concept of “diversity” is not mere lip service. Janson’s goal seems to be no less than changing the way that Canadian film and television is made, and who makes it. That is a seemingly impossible goal, but I can think of few leaders who might be able to make such a dream reality. –Barry Hertz

Dan Levy

“Always leave them wanting more.” Maybe Dan Levy learned that showbiz adage from his father, Eugene, and his honorary aunt, Catherine O’Hara. He certainly applied it when he was arcing out the final season of Schitt’s Creek, one of the brightest stars in the 2020 TV firmament. The CBC series, about a rich, callous family who lose everything and realize they don’t want it all back, had a slow build for three seasons, and then instant success in Season 4, when the world discovered it on Netflix.

It could have gone on and on, but Levy knew it shouldn’t. He gave us a final season that could be its own screenwriting course, in which every character is launched into a new life directly because of what they’d learned in their nowhere-but-everything town. In September, Schitt’s Creek swept the top seven Emmy Awards, a feat no other series had ever achieved. It was an acknowledgement of what a gift Dan Levy gave us, particularly in this COVID year: the chance to miss his characters, and so we love them even more. –Johanna Schneller

Douglas MacEwan

While serving in the Royal Canadian Air Force during the Second World War, young Douglas MacEwan took in a performance of Richard III in London. The actor assigned to the title role that night was one none other than Laurence Olivier. MacEwan had heard “my kingdom for a horse” from the best there ever was. He’s been a fan and patron of the performing arts ever since. As for the horse, with all apologies to Shakespeare, Olivier and Mr. Ed, MacEwan would rather walk.

On Nov. 11 (not only Remembrance Day but his birthday) the 96-year-old veteran and retired Winnipeg radiologist reached his goal of walking a kilometre a day for 96 days. In doing so, he had raised $96,000 (rounded up to $100,000), to be divided evenly between Winnipeg’s four major performing arts organizations: Manitoba Opera, the Royal Manitoba Theatre Centre, Royal Winnipeg Ballet and the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra. The money had been donated by an anonymous benefactor in support of the strolling MacEwan’s beloved institutions, in a time of great financial distress for arts companies devastated by the COVID-19 pandemic. One more mission accomplished for MacEwan. –Brad Wheeler

Jael Richardson

The fifth edition of The Festival of Literary Diversity (FOLD) was set: 29 events were programmed to mark the 2020 milestone. When the world began shutting down in March, FOLD founder and artistic director Jael Richardson acted quickly, moving the festival to Zoom – long before Zoom became a ubiquitous COVID-19 meeting place. She and her team had six weeks to do it.

“I knew we couldn’t cancel,” she says. “We felt like in the midst of the pandemic, it was even more important to put on the FOLD. And to make sure that people from marginalized communities had a chance to connect and find authors and really heal from what was going on around them.”

They held practice runs, worked out technical bugs, set up registration with free tickets. In April, they launched a four-day virtual festival with 16 events that attracted about 5,000 unique participants – up from about 950 the previous year. Not only did FOLD offer cultural respite during lockdown, it also became a model for festival organizers across the country staring down fall events. Richardson answered their questions and created a webinar to share her experiences and takeaways.

The Brampton, Ont. festival grew out of Richardson’s concerns around the lack of diversity in publishing. In this landmark year – with a focus on social justice issues fuelled by Black Lives Matter – Richardson continued to be a critical voice and a formidable advocate. “I think it takes moments like this, where the whole world is watching, to be able to push the needle a little bit further,” says Richardson, who turns 40 on Dec. 26. “For me, this season and FOLD are about continuing to push and continuing to point at where there are gaps.” –Marsha Lederman

Dan Wells

Biblioasis’ Dan Wells has always been willing to take big risks. The first one was starting a press in Windsor, Ont., in 2003, not exactly the centre of the publishing universe. It paid off: The publisher’s books have been long-listed for the Giller 13 times and shortlisted for five; they’ve been nominated for the Weston Writers Trust Non-Fiction Prize, won the Writer’s Trust Fiction Prize once, won the Trillium Book award twice, won the Amazon First Novel Prize twice and won the Governor-General’s Prize twice.

Last year, Wells took another big risk (literally), acquiring Lucy Ellman’s 1,000-page, 2.7-pound tome, Ducks, Newburyport, after her publisher, Bloomsbury, passed. The novel was short-listed for the Booker Prize. Wells started 2020 with a win for the final RBC Charles Taylor Non-Fiction with Mark Bourrie’s Bush Runner. But in a pivot after COVID hit small publishers hard, he made another calculated risk and became a pamphleteer.

In October, he published the first of the Field Notes series: Mark Kingwell’s On Risk. In January, the University of Toronto’s Rinaldo Walcott’s On Property will be available. I expect to see more big moves in 2021. –Judith Pereira

The Globe has five brand-new arts and lifestyle newsletters: Health & Wellness, Parenting & Relationships, Sightseer, Nestruck on Theatre and What to Watch. Sign up today.

Barry Hertz

Barry Hertz Marsha Lederman

Marsha Lederman Brad Wheeler

Brad Wheeler J. Kelly Nestruck

J. Kelly Nestruck Kate Taylor

Kate Taylor