Table of Contents

Non-fiction • Comics and graphic novels • Thrillers • Award-worthy and award-winners • Canadian literature • In translation • Down south and across the pond • Picture books • Young adult

Read The Globe’s guides to living well, from how to shop for wine to how to sleep better

Non-fiction

Boys: What It Means to Become a Man by Rachel Giese (Patrick Crean Editions, 272 pages)

Rachel Giese questions our narrow definitions of masculinity and explores how traditional notions such as “boys don’t cry” and “man up” could soon make way for a revolution in how we raise young men.

Tyrant: Shakespeare on Politics by Stephen Greenblatt (W.W. Norton, 208 pages)

How do seemingly strong institutions suddenly fail? Why do people support a leader they know lies to them? From what psychological lack does a despot’s pathological narcissism bloom? The Bard has much to teach us on these contemporary questions.

All Things Consoled by Elizabeth Hay (McClelland & Stewart, 272 pages)

It is quite simply about death and how it both scours us and educates us. It is also an uncomfortable reminder of what it really means that people are living longer than before.

Hard To Do: The Surprising, Feminist History of Breaking Up by Kelli Maria Korducki (Coach House Books, 144 pages)

One gets the sense that Hard To Do is written for a brand-new kind of young woman – ushered in by the 21st century – who’s stumbling along without the wisdom of mothers or grandmothers to light her path, without even that many books to shape her vision for her life. Unsure, uncertain, not yet fully formed, she is fascinating.

No Place to Go: How Public Toilets Fail Our Private Needs by Lezlie Lowe (Coach House Books, 220 pages)

When you tally all the people failed by our public washrooms – including women, transgender people, those with mobility or incontinence issues, commuters, the homeless, adults accompanying children – it’s actually most of us. The real debate should be why policy-makers don’t consider this a bigger issue.

Heart Berries by Terese Marie Mailhot (Doubleday Canada, 144 pages)

Terese Marie Mailhot tells a story of family dysfunction and abuse, and of a personal reckoning with mental illness. Tough subject matter, yes, but she approaches it with a disarming and often devastating turn of phrase and the evocation of the fragmentary nature of memory.

Mamaskatch: A Cree Coming of Age by Darrel J. McLeod (Douglas & McIntyre, 244 pages)

Darrel J. McLeod remembers an Alberta childhood and a formidable matriarch in his heartbreaking memoir of resilience and family devotion. It picked up this year’s Governor-General’s Literary Award for non-fiction.

Always Another Country by Sisonke Msimang (World Editions, 368 pages)

A memoir of finding home when all one has known is exile. social-justice activist Sisonke Msimang recounts her childhood in exile in Zambia, Kenya, Canada and beyond; her political awakening in the United States and Africa; and her disillusionment upon returning to South Africa.

In Praise of Blood: The Crimes of the Rwandan Patriotic Front by Judi Rever (Random House Canada, 288 pages)

More than two decades later, there remain holes in the history of genocide in Rwanda and the rise of Paul Kagame and the Rwandan Patriotic Front. Montreal-based journalist Judi Rever offers an authoritative account in her new book, sourced from 200-plus interviews and detailed documents leaked from the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda.

Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada by The Royal Canadian Geographic Society (Canadian Geographic, 322 pages)

Three books are each dedicated to a Canadian Indigenous group: Inuit, Métis and First Nations. A fourth volume (Truth and Reconciliation) is composed mostly of maps, with a foreword devoted to the history of residential schools, redress and healing, courts and litigation and the road to understanding.

Big Lonely Doug: The Story of One of Canada’s Last Great Trees by Harley Rustad (Walrus Books, 328 pages)

Harley Rustad bounded down the rocks, through the brush and over fallen logs toward Doug, excited about the reunion. He was bursting with that kind of pride you feel when you introduce someone special to new friends – excited that they get to see, first-hand, the attributes and accomplishments you have come to love. Rustad is a writer; Doug is a tree and the subject of his first book.

I’m Afraid of Men by Vivek Shraya (Penguin Canada, 96 pages)

Vivek Shraya’s latest outing is a slim, accessible work that explores a compelling topic: her fraught relationship with masculinity. Her experiences as a queer trans girl, she writes, place her in a unique position “to address what makes a good man.”

All Our Relations: Finding the Path Forward by Tanya Talaga (House of Anansi Press, 320 pages)

Based on her Massey Lectures series, Tanya Talaga’s collection examines the suicide epidemic in Indigenous communities in Canada and beyond.

The Woo Woo: How I Survived Ice Hockey, Drug Raids, Demons, and My Crazy Chinese Family by Lindsay Wong (Arsenal Pulp Press, 316 pages)

Lindsay Wong was raised in an affluent immigrant family rife with mental illness. Her grandmother was a paranoid schizophrenic; her mother was obsessed with ghosts, or “the Woo Woo,” as they called it. She explores all this in her memoir, which chronicles her life with mental illness, from childhood to her stint at Columbia a decade ago.

Comics and graphic novels

Yellow Negroes and Other Imaginary Creatures by Yvan Alagbé (New York Review Comics, 112 pages)

A landmark of French comics, this decades-spanning collection of terse, leery stories sketches the lives of immigrants torn between France and Africa.

100 Days in Uranium City by Ariane Dénommé, translated by Helge Dascher and Rob Aspinall (BDANG, 144 pages)

In the late 1970s, twentysomething Daniel leaves behind his shiftless lifestyle when he ships out to slog through 100-day shifts in a desolate mining town in the Canadian North. The isolation provides a crucible in which Daniel forges his mature identity – while his cantankerous co-workers lose their own.

Dirty Plotte: The Complete Julie Doucet by Julie Doucet (Drawn & Quarterly, 569 pages)

One of comics' most iconic series from the 1990s is finally collected in one extra-large volume. The Montreal-based artist made waves at the time for her unapologetically raw, purposefully female, sexually explicit comic strips. She may have stopped cartooning years ago, but this book ensures her legacy will have an enduring shelf life.

Sabrina by Nick Drnaso (Drawn & Quarterly, 204 pages)

A young woman’s grisly disappearance is the fulcrum around which everything churns in Nick Drnaso’s consummate sophomore outing. Sabrina’s boyfriend, Teddy, pole-axed by grief, holes up in his former buddy Calvin’s condo. A newly single U.S. airman, Calvin is ill-equipped to deal with such trauma – or the increasingly unhinged online conspiracy theories that beset the two friends and Sabrina’s sister.

Shit Is Real by Aisha Franz, translated by Nicholas Houde. (Drawn & Quarterly, 288 pages)

It is indeed when a brokenhearted woman in a strange near-future slowly ventures deeper and deeper into the life of her glamorous neighbour, who happens to drop her apartment key card en route to a business trip. Beware those who enter. Depression and loneliness – and how people cope – are aptly explored through Aisha Franz’s often surreal pencil drawings.

Young Frances by Hartley Lin (AdHouse Books, 144 pages)

It is an odd thing, a graphic novel about finding yourself through work, but it also includes an unexpected romance. It delivers the ironic outsider viewpoint so central to this populist genre, yet also reproduces some of the whimsy and warmth of the comic book. Hartley Lin’s drawings are both wonderfully approachable and highly expressive.

Berlin by Jason Lutes (Drawn & Quarterly, 592 pages)

One of comics’ great epics finally concludes after more than two decades. Berlin, 1928: Journalist Kurt Severing and art student Marthe Mueller strike up a shaky but intellectually fertile affair. The lives they touch create an encyclopedic cross-section of typical Berliners, a portrait encompassing both workers and beggars, Jews and gentiles, queer life and jazz clubs – and socialists and fascists.

Parallel Lives by Olivier Schrauwen (Fantagraphics, 128 pages)

Six short visual stories about the fantastical futures to come for the cartoonist and his descendants. There are aliens, there are visitors from the even further future, there are secret messages to decode. Could this be reality? Olivier Schrauwen’s surreal style should actually give readers pause.

Somnambulance by Fiona Smyth (Koyama Press, 368 pages)

Known for gorgeous and groundbreaking feminist art, this Toronto legend is poised to break big internationally with her career retrospective. It collects three decades worth of joyfully squishy, hypnagogic riot grrl comics and art, drawn like a mashup of Frida Kahlo and Keith Haring.

Poochytown by Jim Woodring (Fantagraphics Books, 100 pages)

Welcome back to another chapter from Jim Woodring’s Unifactor universe. His wordless comics are best seen rather than written about, as recurring protagonist Frank navigates further into this trippy, psychedelic world that expresses multitudes with opulent black-and-white drawings.

Fiction

Thrillers

This Fallen Prey by Kelley Armstrong (Doubleday Canada, 432 pages)

Kelley Armstrong’s solid Casey Duncan series, set in Yukon, is turning into one of the best new finds of the decade. Armstrong has always been a particular talent, but Duncan and Yukon are definitely her inspiration. Slick plotting and good characters are hallmarks of this clever series.

A Noise Downstairs by Linwood Barclay (Doubleday Canada, 368 pages)

Linwood Barclay is one of Canada’s most successful crime authors, with fans galore. In his latest novel, he’s got his usual suburban setting, but with a twist. There’s a ghost loose in the perfect small town. Is it real or a hallucination? Even with a typing ghost, you won’t put this one down.

Marry, Bang, Kill by Andrew Battershill (Goose Lane Editions, 320 pages)

Andrew Battershill continues to bring his absurdist flair to crime fiction with the story of Tommy Marlo, a mugger who stumbles upon a heist bigger than he can handle. When a hitman pursues Tommy to Quadra Island near Vancouver, both may have met their match among the locals.

Hysteria by Elisabeth de Mariaffi (HarperCollins Publishers, 432 pages)

Novels of psychological suspense revolve around the search for a truth, something that is often elusive and embedded in power. To Elisabeth de Mariaffi, the first layer of fear in this novel is the lost child. But it is more deeply about a woman “who can’t get anyone to listen to her or believe her. That’s really about powerlessness, and it’s terrifying.”

The Bad Daughter by Joy Fielding (Doubleday Canada, 368 pages)

We can always count on Joy Fielding to turn out a well-dressed, well-developed psychological suspense novel, but her recent work featuring therapist Robin Davis is top-notch. The latest is a zippy page-turner with a family secret to be unearthed. This is the kind of tale where Fielding excels and Davis is her best lead yet.

Cold Skies by Thomas King (HarperCollins Publishers, 464 pages)

Who can resist a character named Thumps Dreadfulwater? He’s the Cherokee ex-cop-turned-nature-photographer in Thomas King’s stellar series set in Chinook, Mont., near the Canadian border. The plot, based on water rights, is as up-to-date as this morning’s news. It’s the best of the Dreadfulwater books so far.

Sister of Mine by Laurie Petrou (HarperCollins Publishers, 272 pages)

One of the best first novels this year. This is a brilliantly conceived narrative with wonderful characters and great depth. Hattie and Penny are small-town sisters. It’s clear there are many secrets in their past, some serious enough to make each dependent upon (and frightened of) the other. This is a great psychological suspense novel for a weekend or a plane trip.

Mary Cyr by David Adams Richards (Doubleday Canada, 432 pages)

Literary Canada including Margaret Atwood and Timothy Findley, to say nothing of Michael Redhill, have done mysteries before with great success. So why not the elegant stylist David Adams Richards? This is a marvellously readable saga of a woman who is intrinsically interesting and who moves through a truly memorable life – but there is a mystery in her past that is slowly revealed.

Still Water by Amy Stuart (Simon & Schuster, 336 pages)

Amy Stuart’s debut novel, Still Mine, was highly promising. Her latest brings back the same characters in a new setting and proves that she is no one-book author. Still Water – where Clare and Malcolm return and are hired to track down a missing mother and son – is even better than her debut.

Moon of the Crusted Snow by Waubgeshig Rice (ECW Press, 224 pages)

The rising literary star has created an unsettling story about a snowbound northern Anishinaabe community, where a postapocalyptic reality – no power, dwindling food, chaos – slowly creeps its way through the band. A young man, Evan Whitesky, seeks to restore hope and order to his community by turning to the land – to Anishinaabe tradition. A stellar Indigenous thriller.

Award-worthy and award-winners

Zolitude by Paige Cooper (Biblioasis, 248 pages)

Hadnout

Paige Cooper’s stories all contain similar harsh notes: war, disaster, alcoholism, pedophilia, indentured servitude, police brutality, mistreated dinosaurs. She finds moments of beauty (or maybe it is just truth) in such landscapes. The surreal, sometimes fantastical worlds of these stories are so wholly realized, stepping into them is a pleasing form of disorientation.

The Saturday Night Ghost Club by Craig Davidson (Knopf Canada, 272 pages)

Craig Davidson is back with his first literary fiction since his Giller-nominated, bestselling Cataract City. Davidson returns to magical, seedy, slightly haunted Niagara Falls (a.k.a. Cataract City) for a story about childhood adventures, the human spirit and the haunting mutability of memory.

French Exit by Patrick deWitt (House of Anansi Press, 248 pages)

A story of a mother and her grown son, who lived a life of luxury in contemporary New York until they went broke. They then set sail for Paris. It is unlike Patrick deWitt’s previous work, but it is stamped by his hallmarks: a dry comic touch, delightful and propulsive dialogue and a dab of the fantastic.

Songs for the Cold of Heart by Éric Dupont, translated by Peter McCambridge (QC Fiction, 608 pages)

A century-spanning, 600-plus-page story of one family that bounces from Rivière-du-Loup, Que., in 1919, to wartime Nagasaki, to modern-day Berlin and farther. Éric Dupont’s century-spanning magical realist yarn has drawn comparisons to the work of John Irving and Gabriel Garcia Marquez.

Washington Black by Esi Edugyan (Patrick Crean Editions, 432 pages)

The Giller-winning, historical, coming-of-age tale of George Washington Black, a boy born into slavery on a plantation in Barbados who goes on to much more in the world. And – without spoiling anything – the end of Washington Black is nothing like anything Washington Black himself could have imagined at its beginning.

Beirut Hellfire Society by Rawi Hage (Knopf Canada, 288 pages)

After a friend’s death, Rawi Hage started writing the manuscript that became his fourth novel, his first to return to the Lebanese Civil War since De Niro’s Game. It’s a turbulent and sometimes reckless novel through which many characters blaze for a short time before joining what Hage calls “a parade of deaths.”

The Red Word by Sarah Henstra (ECW Press, 400 pages)

Its setting, an Ivy League school in the mid-1990s, is a representation of university life now familiar to us. Sarah Henstra’s project in a way is to show it to us anew, and to do that she conversely draws upon the very old, including Greek mythology, Homer’s Iliad and the Trojan War. On its surface, this is the story of a battle of the sexes. Its subject, however, is the danger of personal myth.

Motherhood by Sheila Heti (Knopf Canada, 304 pages)

The rather autobiographical examination of what it might mean to be – or not to be – a mother. In her own words: “I wanted to give a sense of how exhausting this question can be and how, in some ways, it just doesn’t end. I mean, you can ask the same question for years and years and years and it’s still the same question. There’s something kind of crazy about that … I wanted to give a sense that it’s endless and maddening.”

Our Homesick Songs by Emma Hooper (Hamish Hamilton, 336 pages)

In a lyrical ode to this country’s easternmost province, Emma Hooper takes readers back to the early 1990s and the beginning of the cod moratorium in Newfoundland. Times are tough and 10-year-old Finn finds people are disappearing. Home has become a ghost town. But soon, his parents vanish – and then his dear teen sister, Cora, too, and somehow he must bring them all back.

An Ocean of Minutes by Thea Lim (Viking, 336 pages)

The time-skipping story of Polly and Frank. In September, 1981, the couple arrive at Houston Intercontinental Airport, where time travel might be their only chance for surviving a deadly pandemic of flu. The premise Thea Lim sets up here allows for the most multifaceted examination of time’s value. Time is Polly and Frank’s shared past and the promise of a shared future.

Something for Everyone by Lisa Moore (House of Anansi Press, 304 pages)

Another short-story collection from the Newfoundland author is the gift that always keeps giving. There is the surreal (Santa Claus and a roof collapse) and the current (a story set in the aftermath of the the Pulse Nightclub shooting) in this go-round. She whets the imagination most when diving into the winded underbelly of St. John’s, and the prostitutes and serial rapists and unsavoury types you won’t find in a tourism ad.

Land Mammals and Sea Creatures by Jen Neale (ECW Press, 288 pages)

Jen Neale’s novel approaches suicide through both realism and magical thinking. In the opening pages, a blue whale beaches itself, seemingly on purpose, followed by the self-destruction of many more animals, birds and sea creatures, all coinciding with the arrival in town of a stranger who is herself obsessed with self-selected death. Such openness on this subject is a welcome change.

Warlight by Michael Ondaatje (McClelland & Stewart, 304 pages)

Every sentence Michael Ondaatje writes defies gravity with its elegance, yet is weighty with significance. Water rushes out of taps “like time itself.” There are baffling loose ends and moments of tension. And yet, underneath the uncertainty, there is a sturdy cohesion that makes this one of Ondaatje’s most successful and satisfying novels.

Dear Evelyn by Kathy Page (Biblioasis, 328 pages)

Although the historical events of its backdrop, the Second World War in particular, clearly influence the family’s lives, the story remains personal and intimate in focus. What this painstaking and painful account of a marriage relies on, as much as its period detail, is its precise ruminations on the nature of affection and resentment, and on how love can persist in the face of cruelty.

Split Tooth by Tanya Tagaq (Viking, 208 pages)

Tanya Tagaq offers a still too rare glimpse of the inner lives of young people, particularly girls and women, living in northern and rural communities. This is her story, “but it’s also not. This book was written for my own heart, and because I’m Inuk – because I’m an Indigenous woman – I’m assuming others will find alignment with it,” she explains. “But also, whoever wants to feel these things, to heal from it or get insight into what it feels like to be an Indigenous woman, it’s like right on.”

Vi by Kim Thuy, translated by Sheila Fischman (Random House Canada, 144 pages)

The deep subject of this story is what Kim Thuy calls “the invisible strength” of women, especially Vietnamese women, whose men, during the war, made a more obvious display of strength as soldiers. Patience, endurance and service to others are the pillars of this strength, which is not all about self-sacrifice. “We often misinterpret Asian women as kind, submissive and obedient.”

Women Talking: A Novel by Miriam Toews (Knopf Canada, 240 pages)

1. Do nothing. 2. Stay and fight. 3. Leave. These are the choices being talked out by a group of women in Miriam Toews’s understated, insistent new novel about sexual assault. It’s quiet, consisting mainly of dialogue among women who have known one another their entire lives, the lack of quotation marks reinforcing that their spoken thoughts are the main story, not accessories.

Jonny Appleseed by Joshua Whitehead (Arsenal Pulp Press, 224 pages)

Every so often, a book comes along that feels like a milestone, with revolution nestled beneath every sentence, every word. This is one of those books. Love, in all its forms, permeates this novel. Complicated love, messy love, nourishing love, platonic love, sexual love, familial love, secret love. Every character in this book is portrayed with empathy and understanding.

Canadian literature

Original Prin by Randy Boyagoda (Biblioasis, 224 pages)

“Eight months before he became a suicide bomber, Prin went to the zoo with his family,” the novel begins. Randy Boyagoda unpacks ideas of faith, fanaticism and family duty, while propelling readers to the final page to find out how his prophetic opening line will come to pass.

Theory by Dionne Brand (Knopf Canada, 240 pages)

Dionne Brand gives voice to a narrator who doesn’t ascribe to gender, known only as Teoria – a tortured academic perpetually led off course by a series of lovers, who each take the “all-knowing” narrator by surprise. Full of wry humour and biting critique, Theory is a masterful work from a writer who still knows how to have fun.

Hider/Seeker by Jen Currin (Anvil Press, 224 pages)

Jen Currin’s characters are often abstainers of one form or another. Or they try. They want to give up booze, they want to give up their former lover, they want to give up being angry. Desire is a difficult thing to excise, though, which is likely why a Zen Buddhist retreat is a recurring setting in these stories.

The Grimoire of Kensington Market by Lauren B. Davis (Wolsak and Wynn Publishers, 350 pages)

After the death by suicide of her two brothers, the author took to the page to make sense of her experience, but memoir didn’t work. Only in adopting the magic of folk tales could she write what she had to say. Readers familiar with addiction will recognize much in Maggie’s journey to find her brother in this story influenced by Hans Christian Andersen’s The Snow Queen.

Sodom Road Exit by Amber Dawn (Arsenal Pulp Press, 408 pages)

Already in decline, Crystal Beach feels haunted – and that’s before Star unwittingly unleashes Etta, the ghost of a professional “screamer” who died in a roller-coaster accident in the early 1940s. Beneath this story is another one, however: As Sodom Road Exit queers the horror genre, it also asks what queer horror includes and how we heal from that trauma.

Heartbreaker by Claudia Dey (HarperAvenue, 272 pages)

The narrator in the middle section of Claudia Dey’s second novel is a dog who named herself Gena Rowlands, but that is not the strangest part. Part of the pleasure of this novel is piecing together the culture that grew in this Petri dish of isolation, as told by people of “the territory” (population: 391) who have known only this. Describing it all here would take the fun out of it.

The Oyster Thief: A Novel by Sonia Faruqi (Pegasus Books, 304 pages)

Greedy human Izar’s quest for aquatic domination threatens the way of life (and actual lives) of mermaid Coralline and her fellow citizens of the idyllic mer-village she has grown up in. And while yes, things get epic and dramatic, the charm of this beguiling novel is in all the details of the underwater world that Sonia Faruqi has dreamed up.

Ayesha at Last by Uzma Jalaluddin (HarperAvenue, 352 pages)

It is very loosely based on Pride and Prejudice, but that’s not the reason to read it. Come for Darcy reimagined as a hyperconservative young man and Elizabeth Bennet as a wannabe poet frustrated by family obligation; stay for Uzma Jalaluddin’s warm portrait of life for twentysomething Muslims in suburban Toronto struggling to honour their heritage while pursuing their dreams.

Twin Studies by Keith Maillard (Freehand Books, 576 pages)

Keith Maillard’s long-awaited new novel opens with an e-mail from twins Jamie and Devon to the Interdisciplinary Twin Studies Program at a Vancouver university. Despite weighing in at 576 pages, it never flags. It turned out to be the perfect length for this story of gender and sexual fluidity and the emergence of one unconventional family.

Late Breaking by K.D. Miller (Biblioasis, 288 pages)

A beguiling marriage of Alex Colville and literature. The painter becomes muse in this interconnected short-story collection, each vignette inspired by one of his canvases. K.D. Miller teases out a unifying theme from his images: that of aging. Loneliness, death and a myriad other maladies pervade the characters, but she is also compassionate in doling out dignity at the end of it all.

The Ghost Keeper by Natalie Morrill (Patrick Crean Editions, 368 pages)

There’s a remarkable scene early in Natalie Morrill’s debut novel. At a New Year’s Eve party, people gather in a bright and merry home away from the crowds. They play music, there are midnight kisses, a young man and woman meet and will fall in love. It is written without a single ominous word, but the reader knows better. For this is 1932, in Vienna. And the celebrants are Jewish.

Little Fish by Casey Plett (Arsenal Pulp Press, 320 pages)

At either end of Casey Plett’s debut novel is a search for queer elders. But this story is ultimately not about the past – it’s about the present, and looking forward to trans futures. Her work is so clearly written for trans women. But the novel also deserves a wide audience. Every reader can get this part: Even as attitudes change for the better, even in a city, being a trans woman is exhausting.

Foe by Iain Reid (Simon & Schuster, 272 pages)

The story of a marriage after one half of the couple is selected by a shadowy organization for a top-secret mission. We don’t learn much about Junior and the past of his wife, Hen – or their near-future world – but quickly and subtly, Iain Reid dissects their marriage with enough passion and pain that the book feels less like a novel than the final pages of a doomed diary.

Trickster Drift by Eden Robinson (Knopf Canada, 384 pages)

Mave is a kind, intelligent, compassionate whirlwind, an Indigenous rights activist and a successful author. She takes in Jared, her 17-year-old nephew and the protagonist of this trilogy. Aunt Mave’s apartment should be a refuge, but Jared, as the son of a trickster, is saddled with supernatural awareness. There’s a ghost watching TV in the apartment and the wallpaper comes hauntingly to life. Monsters appear in unlikely places. But the book is full of light and love.

In translation

The Restless by Gerty Dambury, translated by Judith G. Miller (Feminist Press, 220 pages)

Set during the May, 1967, workers' strike in the French overseas department of Guadeloupe and narrated by a nine-year-old girl alongside a chorus of ghosts, this story is about the psychological manifestations of slavery long after abolition.

Disoriental by Négar Djavadi, translated by Tina Kover (Europa Editions, 320 pages)

A multigenerational epic of the Sadr family’s life in Iran and their eventual exile, as told by former punk Kimia Sadr as she sits in a Paris fertility clinic, this one is full of surprises. Where initially Disoriental seems focused on Kimia’s father and his pro-democracy activism, this is truly Kimia’s story of disorientation – national, familial and sexual – and finding herself again.

Bride and Groom by Alisa Ganieva, translated by Carol Apollonio (Deep Vellum Publishing, 248 pages)

PUR-BK-GLOBE100-1130 book covers

A runner-up for the Russian Booker Prize. Summoned home from Moscow to small-town Dagestan, Patya and Marat both receive a parade of unsuitable matches as their respective parents attempt to marry them off. Of course, Patya and Marat are best suited to one another, and when they meet, the novel takes a turn.

Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata, translated by Ginny Tapley Takemori (Grove Press, 176 pages)

A place called Smile Mart – with its uniformity, orders from head office and demand for sycophancy among staff – might seem the embodiment of soulless drudgery. But for Keiko, the 36-year-old protagonist in Sayaka Murata’s weirdly charming English debut, it represents an escape from the bullying of family, friends and society to find a better job and a partner, to get married and have a baby.

Transparent City by Ondjaki, translated by Stephen Henighan (Biblioasis, 328 pages)

Here, Ondjaki offers an experimental bit of magical realism in a story about a man in Luanda whose body turns transparent – symbolic of the ways the poor of Angola’s capital are made invisible amid rampant oil and water speculation. A prime example of how translation broadens perspective – a diet of English-language writers will likely overlook Portuguese-speaking Africa.

Trick by Domenico Starnone, translated by Jhumpa Lahiri (Europa Editions, 176 pages)

Daniele, the septuagenarian protagonist, ran away from Naples as soon as he could, only to be pulled back against his will when his daughter, Betta, demands he look after his four-year-old grandson while Betta and her husband are away. This, it turns out, is a kind of ghost story, haunted by the same mean streets as those of Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend.

Down south and across the pond

Freshwater by Akwaeke Emezi (Grove Press, 240 pages)

This debut novel is a contemporary, transatlantic story rooted in Igbo understanding. It is also semi-autobiographical, concerning Ada, a Nigerian girl who develops multiple selves, unfolding to a crisis after she experiences a traumatic event at a U.S. university. The feat of this novel is Akwaeke Emezi’s use of language to describe the experience of gods. A true original.

Happiness: A Novel by Aminatta Forna (Atlantic Monthly Press, 368 pages)

Aminatta Forna is particularly adept at writing the politics of life. The Scottish and Sierra Leonean writer’s latest depicts an encounter between a Ghanaian psychiatrist and an American biologist studying urban foxes. It is also a story about contemporary London.

Asymmetry by Lisa Halliday (Simon & Schuster, 288 pages)

Lisa Halliday is more Roth than Roth; in some ways, even more subversive, captivating and labyrinthine. She has said, in fact, she had an affair with Roth, and in one of his final interviews, Roth said this of the novel: “She got me.” It’s tempting to call this a cold dish of #MeToo comeuppance, but this book is a literary event, one of the most engaging, witty reads in ages.

Sea Prayer by Khaled Hosseini (Viking, 48 pages)

Khaled Hosseini’s illustrated book was born from the moment the world learned about a drowned boy named Alan Kurdi. Not as a book, necessarily, but as an idea for action – a way for Hosseini, as he sees it, to create art as an antidote to the dehumanizing effects of numbers and headlines. “Storytelling is not enough,” he says. “But it’s a very important starting point."

Immigrant Montana by Amitava Kumar (Hamish Hamilton, 320 pages)

A young Indian man travels to the United States on a student visa in the early 1990s, where he encounters a gulf of difference between his new home and what he left behind. But in the details, Amitava Kumar reinvents the immigrant novel here, highlighting the way an immigrant story itself is a responsive self-fashioning to the stories that came before.

The Mars Room by Rachel Kushner (Scribner, 352 pages)

With invention, hard-boiled compassion and an arsenal of meticulously researched particulars, Rachel Kushner petitions us to register the dehumanizing absurdities incarceration can inflict upon our fellow human beings. Heroine Romy Leslie Hall’s first-person passages are imbued with intelligence, dimensionality and even integrity.

There, There by Tommy Orange (McClelland & Stewart, 304 pages)

Tommy Orange’s debut novel is a master class in style, form and narrative voice. But will some non-Indigenous readers love this book because it’s an effective, masterful execution of his singular vision? Or will they love it because they can selectively use parts to reinforce problematic ideas about Indigenous peoples? For the sake of Orange’s stunning novel, hopefully it’s the former.

Lake Success: A Novel by Gary Shteyngart (Random House, 352 pages)

In his first novel since 2010′s Super Sad True Love Story, Gary Shteyngart turns his satirist’s eye on modern life for a very few, very privileged – in America. It opens with a Wall Street 1-per-center fleeing his marriage and autistic child … on a Greyhound bus. Super sad, super funny, super Shteyngart.

Picture books

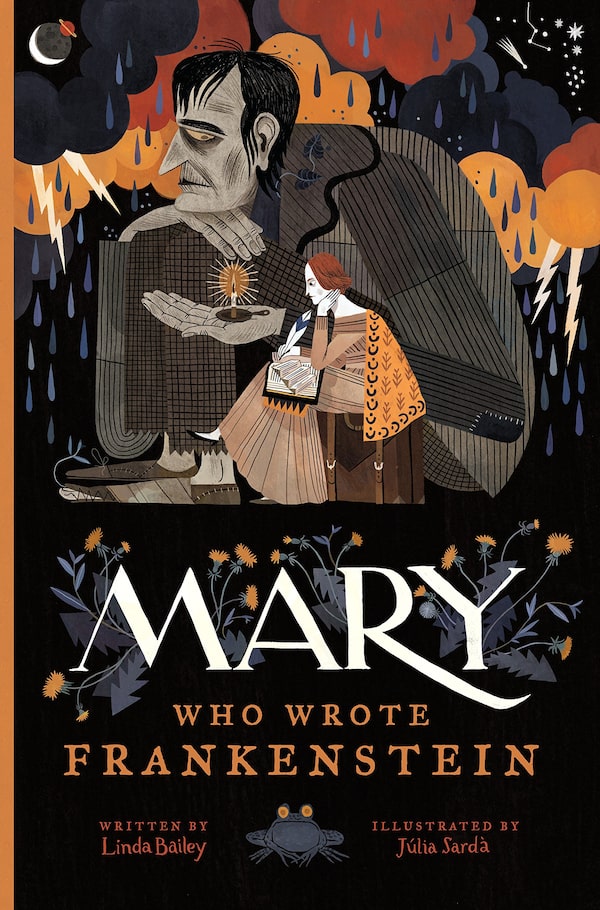

Mary Who Wrote Frankenstein by Linda Bailey & Julia Sarda (Tundra Books, 56 pages)

Mother of the macabre Mary Shelley is front and centre here. Julia Sarda’s mesmerizingly eerie illustrations are not to be missed and this book will find an easy audience among curious older children and adults who never quite outgrew their goth phase.

The Reptile Club by Maureen Fergus and Elina Ellis (Kids Can Press, 32 pages)

This surprising and funny story serves as juvenile wish fulfilment about trying to find others who share your niche interest (spoiler: Sometimes, you need to connect with an anthropomorphic crocodile).

Africville by Shauntay Grant and Eva Campbell (Groundwood Books, 32 pages)

Those desperate to hold on to some feeling of warmer days might find solace here, Shauntay Grant and Eva Campbell take a tactile approach to bringing to life the titular historic community located in Halifax, using a child’s gaze to focus on the details that make a neighbourhood hum.

The Mushroom Fan Club by Elise Gravel (Drawn and Quarterly, 56 pages)

Although the fungi are anthropomorphized with cartoon eyes and goofy grins, the research behind the book is real. Elise Gravel has created a scientific intro book for budding mycologists, combining picture-book artwork with facts about boletes (some turn blue when touched) and the Lactarius indigo (which produce a milk-like substance when cut open).

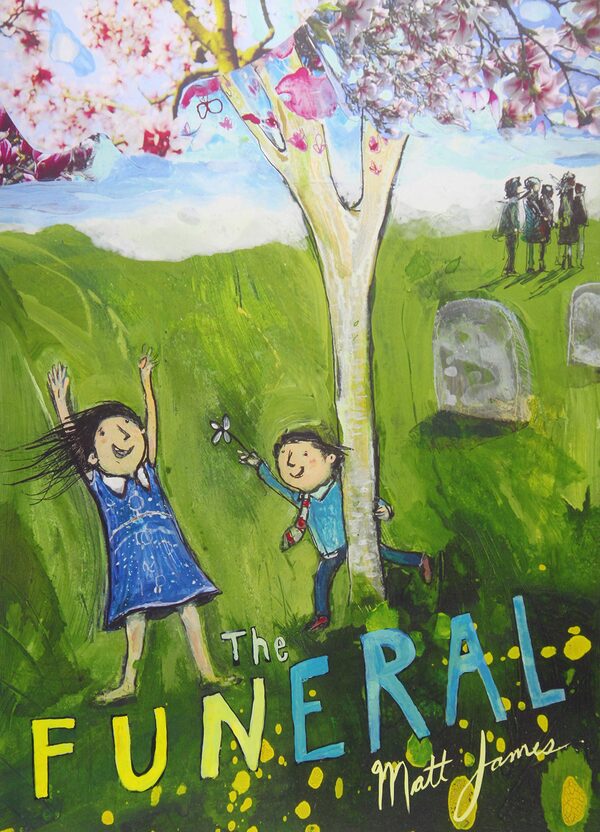

The Funeral by Matt James (Groundwood Books, 40 pages)

Many sombre books have been written in an attempt to explain the concept of death to children, but few have done so as creatively and playfully as this one, where Norma hasn’t quite grasped what it means that her great-uncle Frank has passed away. It’s an unexpected but realistic take on the simple ways in which kids process serious events around them.

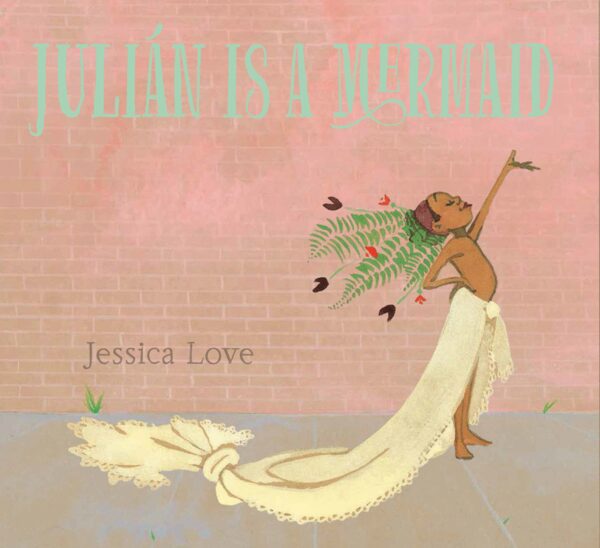

Julian is a Mermaid by Jessica Love (Candlewick Press, 40 pages)

A boy riding the bus with his abuela (Spanish for grandmother) becomes transfixed watching women in their shimmering costumes and lush headdresses (en route to the Coney Island Parade, perhaps?). The text is sparse, as much of the book follows Julian by himself, wondering how he can imitate their look. It’s an intimate story with lofty ambitions about radical self-acceptance.

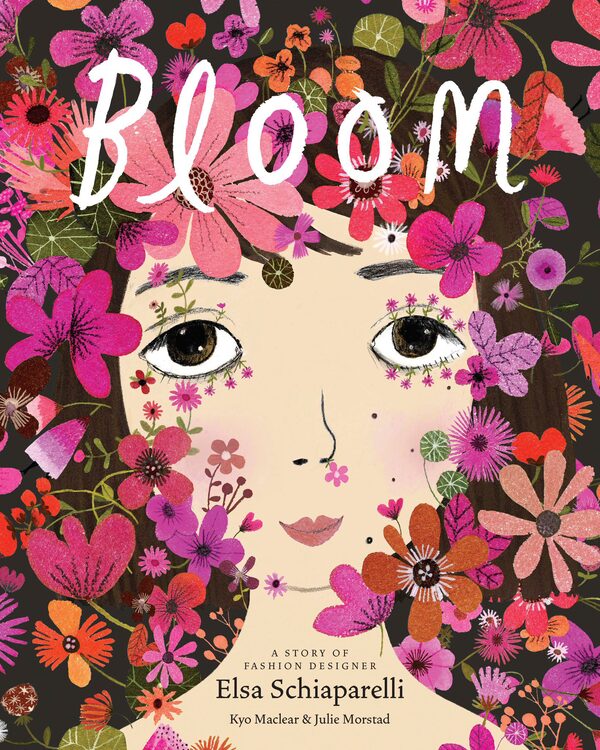

Bloom by Kyo Maclear and Julie Morstad (Tundra Books, 40 pages)

It’s hard to say how much interest a child might ordinarily have in the legacy of surrealist fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli, but the lives of iconic women continue to serve as inspiration for modern stories. She serves as the subject for this book, and Kyo Maclear and Julie Morstad do well to find the timeless aspects of her life while introducing the historical contexts of the rest.

Grandmother’s Visit by Betty Quan and Carmen Mok (Groundwood Books, 32 pages)

A unique exploration of grief and the ways in which storytelling can explain the concept of death to smaller children, told through a gentle pacing that gives space to the complicated feelings of mourning.

Backyard Fairies by Phoebe Wahl (Tundra Books, 32 pages)

They’re real here. A girl searches for them in her yard and beyond – and searches and searches. Where could these magical creatures be? Young readers will be able to spot what’s just out of reach for the protagonist. What’s hidden in plain sight is rendered into a magical adventure that rewards careful attention to Phoebe Wahl’s textured illustrations.

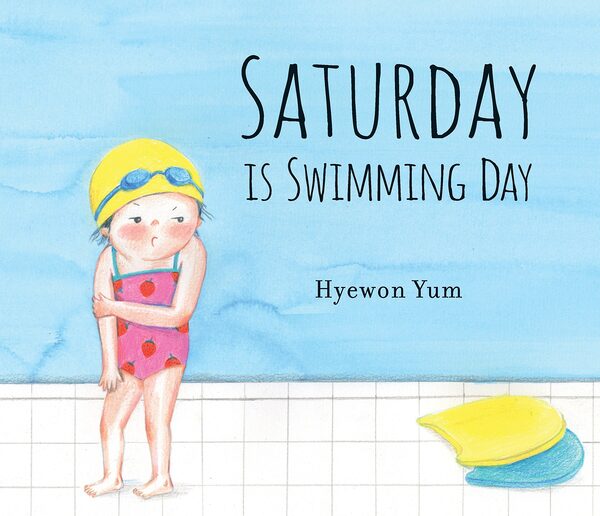

Saturday is Swimming Day by Hyewon Yum (Candlewick Press, 40 pages)

When her weekly swimming lesson comes around, one girl experiences a stomach ache and chooses to sit out. Thanks to the patience of her swimming instructor, the girl is given the space she needs to become comfortable enough to join the class. It’s a quietly brilliant book about helping a child cope with anxiety.

Young adult

A Girl Like That by Tanaz Bhathena (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 384 pages)

Tanaz Bhathena does something exceptionally difficult and smart in her first book. She draws in readers with an irresistible “Who is she?” premise, only to dismantle it by showing the rarely seen perspective of a teenage girl living in the Middle East.

Tess of the Road by Rachel Hartman (Penguin Teen, 544 pages)

Like the best fantasy, it overflows with pragmatic truths, but on topics you might not expect, including self-worth, consent, gender roles, transitioning to adulthood and taking pleasure from sex. It reads like wisdom of the ages targeted right at people growing up in this (insane) age.

Hey, Kiddo by Jarrett Krosoczka (Scholastic, 320 pages)

An illustrated memoir about the author’s troubled childhood. His mother is a heroin addict and his father is non-existent. He’s raised by his grandparents, who are often equally doting and drunk. As a teen, he is just about ready to face the truth of his family’s turmoil – and always emotionally supporting himself along the way with the art that would become his life’s work.

Learning to Breathe by Janice Lynn Mather (Simon & Schuster, 336 pages)

Janice Lynn Mather’s debut novel tackles rape and teenage pregnancy through an Afro-Caribbean lens. Indy is forced to hide her unwanted pregnancy from family as she must make tough decisions that will affect the rest of her life. On the streets of Nassau, she happens on a yoga retreat – a place where the people help steer the final course of her story.

Blood Water Paint by Joy McCullough (Dutton, 304 pages)

A deeply researched historical fiction inspired by the life of the Italian baroque painter Artemisia Gentileschi: Her art, her childhood, her rape by a fellow artist and the subsequent trial during the 1600s. Although her story has been recounted before in popular culture, Joy McCullough tells it as a captivating teen tale filtered through feminism and with echoes of the #MeToo movement.

This Book Betrays My Brother by Kagiso Lesego Molope (Mawenzi House, 192 pages)

A story of a brother told through the overshadowed voice of his sister, a poignant device for examining systemic racism, sexism and poverty in the years after apartheid in South Africa. She has her own life and story to tell, but her brother is the centre of the family. But when she witnesses him committing a heinous act, her understanding of family and loyalty is put to the test.

Nice Try, Jane Sinner by Lianne Oelke (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 432 pages)

The debut Vancouver author proves that the first year out of high school can be full of personal growth and reflection – even while starring in a low-budget reality show at a community college in Elbow River, Alta. Jane Sinner’s story is for those who like their books brainy and their television trashy. A binge read with hidden depths.

Not Even Bones by Rebecca Schaeffer (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 368 pages)

A supernatural thriller about a mother and daughter in the black market business of supernatural body parts. But when Nita begins to grow a conscience about their family trade, she finds herself – and her own supernatural biology – sold off to the highest bidder. We find out what makes a monster in this world, with plenty of grisly action spliced throughout.

Sadie by Courtney Summers (Wednesday Books, 320 pages)

Nineteen-year-old Sadie goes missing shortly after the brutal murder of her 13-year-old sister, Mattie. This is a crushing, unforgettable YA crossover novel that will have massive appeal for adults.

The Prince and the Dressmaker by Jen Wang (First Second, 288 pages)

In this fairy tale, a seamstress named Frances forms a fast friendship with Prince Sebastian after discovering their mutual love of design. This graphic novel contains the happiest jaw drop of an ending. It’s a joyful, loving, hug-the-world feeling that will stick with you all day.