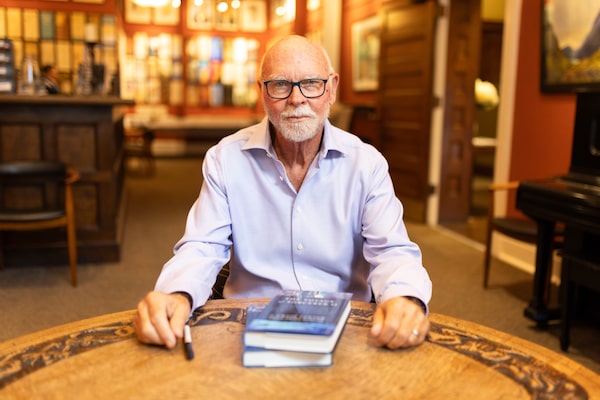

Scientist and author J. Craig Venter signs copies of his new book Sorcerer II: The Expedition That Unlocked the Secrets of the Ocean’s Microbiome at the Arts and Letters club in Toronto, on Oct. 26, 2023.Melissa Tait/The Globe and Mail

The expedition to crack open the ocean’s genetic treasure chest began in Halifax harbour under an overcast sky.

It was Aug. 20, 2003. J. Craig Venter, the geneticist turned entrepreneur, had arrived with the captain and crew of Sorcerer II, his 95-foot sailing yacht that doubled as a floating field laboratory. His mission: circumnavigate the globe while sampling the ocean waters along the way. It was to be a planet-wide DNA test that would shed light on the full breadth of the ocean’s genetic diversity in a way that had never been attempted before.

Venter was not a novice – to sailing or to mounting large and transformational science projects aimed at overturning the conventional wisdom of his peers.

“Everyone thinks that new discoveries are about making breakthroughs,” Venter told an audience during a recent visit to Toronto, where he sits on the science and innovation advisory committee for the Hospital for Sick Children. But often, discoveries simply overcome bad ideas of the past, he added.

Now 77, Venter was 56 and newly unemployed when he decided to travel around the world by sailboat. By then he was already a world renowned scientist and a notorious iconoclast. His innovative approach to genetic sequencing in the 1990s had allowed him to race the massive Human Genome Project mounted by the U.S. National Institutes of Health. The effort reached its culmination in the summer of 2000 with the unveiling of a first draft of the full human genetic code three years ahead of schedule by the NIH and Celera Genomics, the company Venter co-founded in 1998.

The joint reveal, brokered by the White House, kept the focus on the future benefits of the achievement for humanity, but Venter has never been shy about saying he won the race. Eighteen months later he was fired from Celera because the leadership of the firm’s parent company “decided they didn’t need this radical scientist any more,” he said in an interview with The Globe and Mail.

What followed is documented in The Voyage of Sorcerer II, a book by Venter and his co-author, science writer David Ewing Duncan, that provides a personal account of a unique expedition.

For Venter it was to be the ultimate midlife reset – not to mention a chance to irk colleagues in academia and government who were locked into a more conventional approach.

Supplied

It was “my best idea,” he said. “I found a way to sail around the world on my own boat and do science and get paid for it.”

It was also Venter’s golden opportunity to finally pursue science in a way that most excited him, as it was once done by Charles Darwin and other 19th-century pioneers: by looking and seeing what’s out there without any idea what might turn up.

Even the choice of Halifax as the expedition’s official starting was a kind of homage to this idea. Halifax had also been visited by HMS Challenger in 1873, the first expedition to survey life in the global ocean’s depths.

That historic voyage famously showed that the seafloor was not a biological desert sterilized by extreme conditions, as some thought at the time. No matter how deep, the ocean was occupied.

Venter frames his own voyage in similar terms, as showing that microbial life in the ocean is far more diverse at the genetic level than expected.

His first run at the idea came with a sailing trip in the spring of 2003 to sample waters in the Sargasso Sea, a portion of the Atlantic Ocean east of Florida where drifting micro-organisms are partly confined by currents.

A small team including expedition scientist Jeff Hoffman filtered some 400 litres of seawater to capture bacteria and then froze the contents for detailed analysis on land.

The results were obtained using the same “shotgun sequencing” technique that Venter had applied so successfully to the human genome. It starts with pulverizing DNA into short random strands that can be read by sequencing machines and then using a computer algorithm to match overlapping readouts from the fragments to reconstruct a complete genetic sequence.

But now, instead assembling the code of a single organism, the algorithm might be working with DNA from many separate bacterial species, invisible and indistinguishable from one another except through their genetic fingerprints.

The result “blew our minds,” said Venter. The Sargasso Sea was teeming with diversity. As detailed in a research paper based on the analysis, the team found 1.2 million newly reported genes from at least 1,800 species including bacterial groups previously unknown to science.

It was an impressive haul but Venter was already working on a far more ambitious sailing trip to gather samples from around the world and show not only the vast richness of microscopic life in the seas but its variation from one location to the next. The uniform blue expanse that represents the ocean on a world map might, in reality, be subdivided into countless microbial domains, evidence of the dynamic multibillion-year evolutionary history of life on Earth.

By summer the expedition was coming together, drawing skepticism from some but also winning early support from some powerful allies, including Ari Patrinos, who was then director of biological research at the U.S. Department of Energy and key funder. Another supporter was the late E.O. Wilson, the celebrated Harvard University biologist.

“He liked that I was asking global questions and treating it as a much big picture,” Venter said.

The expedition’s first sample was collected in Halifax Harbour followed by a road trip by Venter, Hoffman and others across the width of Nova Scotia to scoop water out of the Bay of Fundy with the help of a local fisherman. The drive included a visit with Victor McKusick, the Johns Hopkins University professor known as the father of medical genetics, who had a summer home in the area.

The Sorcerer II soon headed back down the Atlantic coast, first to Hyannis, Mass., and then Annapolis, Md., for a final series of preparations that would allow the ship, under the guidance of Canadian-born Captain Charlie Howard, to travel the open ocean for months-long stretches without support.

In December the sailing and the sampling continued, with the ship making its way to Florida and on to the Caribbean and the Panama Canal. Venter’s initial plan had been to sail around South America but the time of year combined with the treacherous currents around Cape Horn ruled out a long journey around the continent. And there was the likelihood that Brazil would not permit sampling in its territorial waters – a harbinger of the growing debate over who holds sovereignty over genetics information obtained from the environment and any future profits that such information may generate. Although the expedition’s findings were always intended to be made public domain, Venter had already been branded “bio-pirate of the year” by one environmental group ahead of the voyage.

Sorcerer II entered the Pacific via the Panama Canal and onto the Galapagos Islands, following in Darwin’s footsteps but with the added complication of negotiations over permits and transport of samples back to the United States. The joy of exploring the biological wonderland shines through in Venter’s account, as he and his colleagues search for unique environments to sample, including a hydrothermal vent off Roca Redonda, a tiny steep-sided island that is the eroded remnant of an underwater volcano.

From the Galapagos the crew travelled west across the South Pacific, sampling the waters roughly every 200 miles.

“That’s roughly how far you can sail in 24 hours in a decent-size sailboat,” Venter said. “And so we’d stop once a day and take a sample.”

What the scientists on Sorcerer II found was that, at each stop, more than 80 per cent of the genetic sequences was “totally new and unique,” Venter added. The ocean was, as he had guessed, a far more complicated and genetically diverse patchwork of microscopic ecosystems than had once been supposed.

Other adventures were to follow, including an encounter with a SWAT team in Brisbane, which had been called to investigate whether the ship was a floating meth lab – apparently the work of a jilted fiancé whose former partner had become romantically involved with one of the crew. Later, some of the tensest moments of the voyage came during a stop at the Chagos Archipelago in the Indian Ocean where the crew had their passports seized by the British military, who threatened to impound the Sorcerer II until Venter was able to reach the U.S. ambassador to the United Kingdom by satellite phone.

The circumnavigation was completed in January, 2006, when the ship reached Palm Beach, Fla., nearly two and half years after departing Halifax. But it was only to be the beginning of a more sustained campaign of ocean sampling that would next take the ship up the Pacific Coast to Alaska and then on a trip through European waters from the Baltic to the Mediterranean. Further excursions to Antarctica and the North Atlantic followed as the sampling work continued until 2018.

The final section of the book details the research results that have issued from the work, including insights into the active role that viruses play as managers of the marine ecosystem with implications for how nutrients cycle through the oceans.

The most significant impact of Sorcerer II’s voyage may be that it signalled the coming of age of metagenomics, the now widely employed technique of sampling the environment rather than organisms directly to understand the biology of the planet. It is an approach that has seen the merge of a revolution in genetics with big data and computational tools.

Despite Venter’s reputation as a pioneer in the use of algorithms to advance genomics, he takes a measured view of the role that AI will play in biology’s next chapter. Algorithms are tools that are only as good as the data they are trained on, he said. Ultimately it’s the mind of the scientist, and the spirit of discovery that gives direction and meaning to the scientific process.

For all its power, he added, AI “can’t answer questions about the unknown.”

Ivan Semeniuk

Ivan Semeniuk