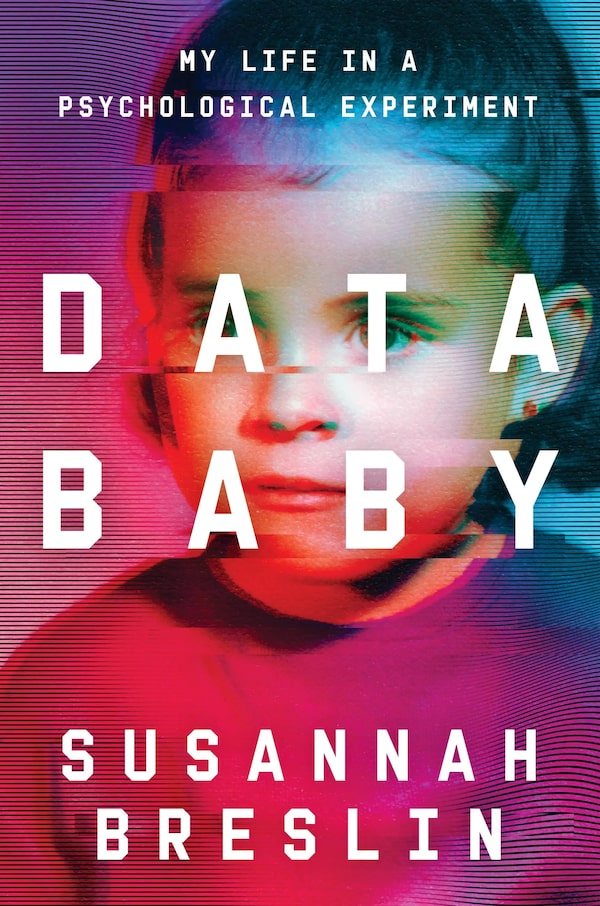

- Title: Data Baby

- Author: Susannah Breslin

- Genre: Non-Fiction

- Publisher: Legacy Lit

- Pages: 224

When we talk about a child’s need to feel seen, we aren’t generally talking about being seen through one-way glass by clipboard-wielding psychologists. And yet journalist Susannah Breslin’s astonishing memoir, Data Baby, suggests that, absent a nurturing family environment, that arrangement may be better than nothing.

Shortly after her birth in 1968, Breslin’s parents, both literary academics, enrolled her in a 30-year psychological experiment dubbed the Block Study, after its married founders Jack and Jeanne Block, run out of the University of California, Berkeley. Its aim? To predict who its 100-plus participants would become as adults.

Books we're reading and loving this week: Globe staffers share their book picks

Admittedly, the spirit of scientific inquiry was less a motivating factor for Breslin’s parents than the convenient, affordable child care the study’s laboratory/preschool was offering. For Breslin’s mother, in particular, the respite would be a chance to fulfill the scholarly ambitions she’d put on hold when she had children.

But it also made her realize she didn’t much enjoy motherhood, something she didn’t hesitate to impart to her daughter. Already emotionally distant and depressive, Breslin’s mother became more so after she and her husband divorced when Breslin was a tween. Hungry for attention, Breslin acted out in ways that ensured she got the wrong kind: She did drugs, had sex, got into fights, let her grades slip.

Until her “participation” in the study was finally revealed to her in her later teens, Breslin had become accustomed to strange people suddenly appearing by her side at school and at home. Some took her to rooms to do puzzles, watch her play, inquire about her family life and morals or administer snap Rorschach tests.

Once, in an incident that would come to haunt her (she later realized it was a twist on the classic marshmallow test on delayed gratification), an examiner offered her a giant bowl of M&M’s. Worried that this person might, like her mother, call her “piggy” if she accepted, Breslin declined. When the examiner made an excuse to step out of the room, Breslin attacked the candy so ferally that the entire bowl spilled over, leaving her scrambling to clean it up.

For the most part, though, these interactions didn’t make her feel strange or paranoid, they made her feel special. Unlike her work-obsessed parents, these mysterious people seemed to hang on her every word, nodding encouragingly when she gave them her solicited views.

Which led, in the long term, to confusion. Asked to personally assess how her life had turned out when she was discharged from the study, at age 32, Breslin was aware that her “responses had a positive spin, as if I were a child seeking to impress a parent I had seen infrequently and not in a long time.”

When it came to avoiding the observer effect, the Block Study failed spectacularly. It even influenced her choice of profession. By observing “their close study, active listening, and studious note taking,” Breslin contends that her examiners effectively taught her how to be a journalist.

When it’s not delving into such ironies and paradoxes, Data Baby gives us a dispassionate but engrossing account of the life the Block Study sought to predict: A journalism career that began with a pioneering sex blog and a deep dive into California’s porn industry coupled with frequent moves, impulsivity and a string of failed relationships.

And the crises. Shortly after she marries a controlling, quick-tempered veteran of the Iraq War in Las Vegas – nine days after their first date – Breslin is diagnosed with an aggressive form of breast cancer. She survives. Unsurprisingly, the marriage does not.

A move to New Orleans ends up with a narrow escape from Hurricane Katrina. For the next few years, Breslin finds herself adrift, struggling with depression and PTSD. Unable to write, she takes a job as a waitress.

With her future uncertain, she decides to delve into her Block Study past. She finds the study’s dataset online. Though anonymized, it contains enough breadcrumbs to allow her to figure out her subject number. She also learns that, owing to custody battles over the data, much of it was left unanalyzed after the 2010 death of Jack Block.

Intrigued, she lands a fellowship that will enable her to move back to the Bay area and take on the project full-time. As she wanders the semi-abandoned rooms and buildings, now a kind of memory palace, in which she was once a “human lab rat,” Breslin’s quest takes on a distinctly existential cast: “I had fantasized that by finding my data I would find the real me.” She imagines becoming “my own observer effect, changing the story of my life as I revisited, revised, and retold it.”

Based on its cover, you might imagine that Data Baby is about the ethics of studying children without their consent. But Breslin knows that, given the constant digital surveillance by multibillion-dollar tech companies, that’s an almost laughable idea these days. “Big Brother is watching us,” she writes, “and the goal isn’t scientific enlightenment but social engineering for profit.”

If, as Socrates contended, “the unexamined life is not worth living,” then Breslin is living hers to the fullest. Lucky for us, she’s written a thought-provoking, ridiculously propulsive book about it.