Lucy Lu/The Globe and Mail

Lois Cormack, then 15 years old, pedalled her bicycle down a dirt road from her family’s farm near Cannington, Ont., to begin her first job at a local retirement home. She didn’t realize it at the time, but that day would launch a lifelong career in senior care.

Over those initial few weeks working with seniors, she observed that the owner—a woman in her 70s—called the shots not only for the team of nurses, chefs and program co-ordinators, but for the business as well. She tackled problems for staff and seniors while also considering the needs of a capital-intensive, resource-squeezed enterprise. She wielded the power to make big, impactful changes. Cormack admired her for it.

“I thought, That’s what I want to do—I want to be her,” Cormack says. “I realized very early on that you have to have a position of influence to make really significant change—you can’t really do it at the front line. You might make a difference in the lives of residents and team members, but you won’t have a significant impact on the business. So that’s what I set my sights on.”

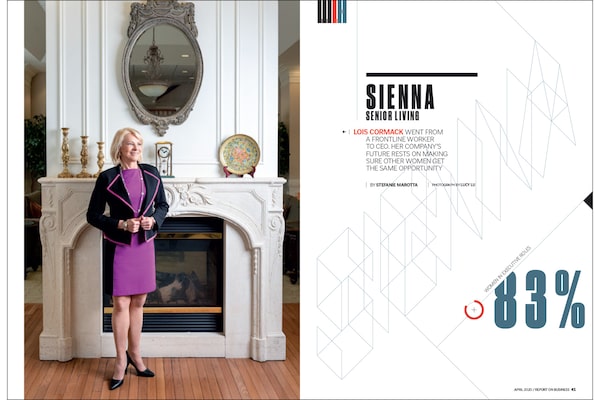

More than four decades later, the 58-year-old president and CEO of Sienna Senior Living Inc. is the head of an organization with more female leaders than almost any other publicly traded company in Canada. Across the enterprise, women compose 83% of its senior executive team and 79% of executive directors in charge of its retirement residences and long-term care (LTC) homes. At the Markham, Ont., firm, gender diversity is reflected across the enterprise, from the C-suite to the managers of its local residences.

Women have led the company through a period of rapid growth driven by a growing retirement population. Cormack, who joined as CEO in 2013, has steered Sienna through an enterprise-wide rebranding as well as a cavalcade of acquisitions. She expanded the company from 30 properties to 83 long-term care and retirement residences in British Columbia and Ontario, making it the largest owner and operator of LTC facilities in the latter province. A central tenet of her strategy has been drawing on the expertise of her front-line staff—and then empowering them to become management. After all, Cormack started on the front lines herself.

Cormack spent years as a personal care worker and nurse before finally climbing into the leadership role she aspired to as a teenager. Eager to be part of her industry’s business operations, Cormack pursued a part-time business degree and then launched a consulting firm focused on senior care that did work for the Ontario Ministry of Health. From there, Specialty Care, a private, family-owned senior living management business, recruited her into its ranks.

In 2013, Leisureworld Senior Care Corp., as Sienna was formerly known, acquired Specialty Care, where she was then president. Leisureworld began as an operator of LTC homes. After going public in 2010, it began diversifying into retirement residences, where pricing is more flexible compared with the world of government-regulated long-term care. The $254-million acquisition of Specialty Care added 10 new properties to its portfolio, increasing its retirement suites by 44%. Cormack became CEO of the expanded firm.

She inherited a company that was a collection of sub-brands, the result of recent acquisitions. After a six-month tour, visiting properties and hosting town halls with staff and seniors, she decided big changes were required.

“I realized there wasn’t a common vision, mission or values across the company,” she says. “The company had just entered into retirement housing, which was considered high-end luxury, but we also had long-term care that had a compliance-oriented culture. There was also the home-care business that thought it was completely distinct and didn’t see itself as part of the company.”

To streamline the company’s disparate operations under one brand, Leisureworld became Sienna. Individual facilities, which previously bore the Leisureworld name plus the city it was located in, were rebranded with locally inspired monikers that reflect the surrounding community (for example, Kawartha Lakes in Bobcaygeon, Ont.; and Kensington Place in Toronto).

Cormack also overhauled the corporate culture’s top-down approach to give greater authority to the people who spend their days interacting with residents. One of the earliest changes involved transferring responsibility for program scheduling from head office to the executive directors at local facilities. Through this approach, company processes became more efficient for personal-care workers, nurses and administrators over an 18-month period. Having experience in one of those on-the-ground positions started to carry greater weight when the company was recruiting for leadership positions. “We tried to grow from within,” Cormack says. “We would rather take a personal support worker and help her become a nurse or a director of care.”

Of Sienna’s 12,000 employees, 8,000 are front-line workers. They care for seniors, tend to complex medical needs, build meal plans and schedule activities for residents. But if workers don’t have a business education, climbing from the front line to the C-suite is a difficult journey—one that Cormack understands well. With that in mind, she set about recalibrating how Sienna approached recruitment and development.

Changing the company’s culture required someone who understood the complicated, demanding world of senior care. So she brought on Joanne Dykeman, a registered nurse with executive experience, to oversee the LTC homes and residences scattered across Ontario and B.C. The pair began implementing education programs to teach business skills to frontline staff.

For example, Dykeman points to a certificate her team developed with York University. Sponsored by Sienna, nurses attend the year-long Director of Care Certificate in Clinical Leadership program to learn how to run parts of a senior-care facility. At the executive level, local residence managers can move into senior leadership roles while completing business degrees part time. “I’m very comfortable bringing people in if the fit is right and then helping them complement their experience with formal academic preparations,” Dykeman says. “It’s not just about getting an MBA. If you have the experience and are a good fit, we’ll work with you.”

Sienna’s focus on supporting its employees has caused the number of internal promotions to increase each year. Today, internal promotions make up 55% of leadership roles, up from 33% in 2015. And women hold 77% of leadership positions.

Competition for talent will only intensify in the senior-care industry. Companies like Chartwell Seniors Housing Real Estate Investment Trust and Extendicare are ramping up construction to capture a share of a growing market. This increased pressure has meant a drop in occupancy rates in some of Sienna’s retirement residences, even as it undertakes a slew of renovations to add beds at many of its properties.

Despite these pressures facing Sienna, analysts remain upbeat about its prospects. “There has recently been an increase in seniors’ housing development in certain markets, which has led to temporarily elevated competition for seniors’ housing operators and lower occupancy rates,” says Brendon Abrams, an analyst at Canaccord Genuity Corp. “However, given the anticipated demand from Canada’s growing senior population, we expect the new supply to be absorbed by the market over the next few years.”

Cultivating internal talent will become increasingly important as the company confronts these long-term trends, according to Cormack. Retirement residence demand will outpace supply by 2023 in Sienna’s key markets. Between an aging population, a shortage of health care workers and competitors eager to poach employees, Sienna remains focused on finding new ways to train its people.

Women on the front line of senior care will have greater opportunities to grow and develop—but only if executives support them, Cormack says. “It’s about really helping them get there and leaders looking out for them, even if it’s in going back to get a degree,” she says. “You can do this. Our CEO was a personal support worker, so if that’s what you want to do, you can do it. There’s a path to get there.”

Lois Cormack went from a frontline worker to CEO. Her company’s future rests on making sure other women get the same opportunityLucy Lu/The Globe and Mail

Stefanie Marotta

Stefanie Marotta