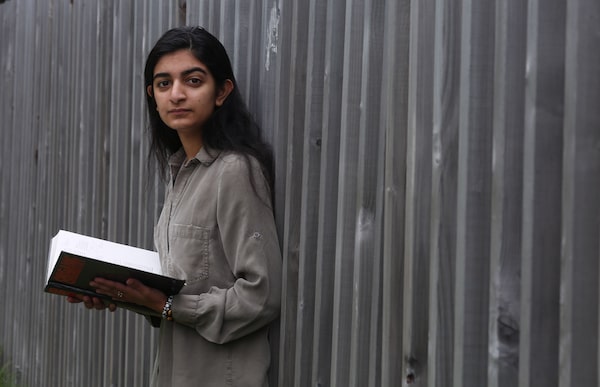

Mahima Mishra, 21, is going into her third year of pharmacy at Memorial University in St. John's. The pressure to be the best in high school 'consumed almost every aspect of my life,' she says, but in university she learned to set her own expectations and focus on what matters.Paul Daly/The Globe and Mail

The texts started once Sara Dimerman’s daughter arrived at university. The fan in her dorm room was making weird noises. A stain on her duvet cover wouldn’t come out. Should she buy one lemon or a whole bag? In a new book retelling that first year, Ms. Dimerman, a Toronto psychologist, describes patiently brainstorming one problem after another via text. Cutting the cord doesn’t happen with one sharp snip, on either end. But at one point, after getting a text that says plaintively, “I feel very sad that things are breaking,” any mom might wonder, is all this reaching out really about lemons and laundry?

Parents have good reason to go searching for emotional subtext: The numbers of high-school and university students who report struggling with depression and anxiety are rising, crowding school counselling services and emergency rooms. In part, this is evidence of a new generation more open to seeking help for mental illness. But what’s behind all the stress and angst? The list of suspected environmental toxins is long: The race for Instagram likes. The doomsday narratives of the 24-hour news cycle. The fear of failure.

Universities are increasingly investing in programs and counselling services to improve mental health for students, upon arrival. One example: A 10-hour program at Dalhousie University in Halifax, called Q-life, has students complete a mental-health survey to identify strengths and potential issues, watch training videos on resilience and complete a workbook to teach coping skills.

But a collection of recent books by mental-health experts proposes that young people require more on their what-to-bring-to-university list than toiletries and cooking lessons. They need a resiliency booster to steady them against inevitable, everyday stress.

These authors approach the issue from different angles, but their conclusions are similar. When parents focus too much on grades and college applications and even laundry skills, what often gets neglected are the life lessons that guide teenagers along the path to happiness and well-being: How to tune out all that white noise and prioritize what matters.

More and more, Canadian universities are offering mental-health services and counselling to help students adapt to the pressures of school and life.Chris Young/The Canadian Press

CALL STRESS WHAT IT IS – GOOD AND BAD

To begin with, let’s stop using the word stress when we mean something else. An American study published in June in the journal Emotion suggests being more precise in describing emotions – I feel frustrated this happened; I am nervous about that – helps young people better manage daily hassles, and reduces the symptoms of depression. Being specific identifies solutions for negative feelings. By comparison, the word “stress” is unhelpfully vague.

“Somehow, we are supposed to be stressed enough to put in effort, but not too stressed or we’re being dramatic and attention seeking,” says Morgan Burton, who is going into her fourth year as a history major at the University of Lethbridge in Alberta. This belittling of the stress that teenagers feel, she says, makes it harder for adults to teach them how to recognize and manage stress that is healthy, protective and performance enhancing.

In her recent book, Under Pressure, Ohio psychologist Lisa Damour explores stress and anxiety specifically among girls. Among her recommendations is teaching teenagers that most of the time the physical signs of stress – a racing heart, nervous tension – are their body and brain revving up for a difficult task. How often do we say, “I am so stressed,” in an exam-conquering kind of way? Research has found that how people view stress – as either useful or debilitating – affects their responses to it. Teens should be taught that while stress can feel uncomfortable, in manageable amounts, it can improve their performance of difficult tasks.

Michael Ungar of Dalhousie University is the author of Change Your World, a book on the science of resilience.Tijana Martin/The Globe and Mail

MAKE ROOM FOR STRESS TRAINING

Responding well to stress, like any skill, requires practice – learning how to cope with manageable stress prepares us for future stress, a pattern that researchers called the “steeling effect.”

As Dalhousie researcher Michael Ungar, the Canadian Research Chair in Child, Family and Community Resilience, writes in his new book on resilience, Change Your World, a person’s “capacity to withstand and learn from stressful experiences hinges on how well resourced they are before and after the stress occurs.”

That includes prior exposure in small doses – a difficult test they force themselves to take, a nerve-wracking public speaking event – to help them manage the big events, such as a loved one’s death, or an illness. What worries Dr. Ungar is that today’s children, protected from even minor adversity, are not prepared for the stress of adulthood, or for the environment that awaits them.

LEARN HOW TO FIND A POSITIVE PATH WHEN ADVERSITY HAPPENS

Dr. Ungar’s book suggests that what our children need from us are not solutions. Instead, they need to know how to ask solution-seeking questions: Where can I get help? What have I learned? How much does this matter to me and my life?

For half a century, he writes, we have known that three steps are necessary to cope with misfortune – to understand the nature of the stress, to identify the meaning that we are giving that stress, and to have resources to manage that stress. This is the practice of resilient people – name the problem, give the problem perspective and then access solutions to the problem.

“We are more resilient when we have encountered a manageable amount of stress and have the resources required to put our lives back in order,” he writes. “If children today seem to us vulnerable or unable to look after themselves we need to stop blaming them and start pointing the finger where it belongs.”

Too often, parents rescue their kids from stress, when what they really need is supportive coaching.

Ms. Mishra says she felt like she was 'racing for a finish line that didn’t exist.'Paul Daly/The Globe and Mail

SEE FAILING AS THE SECRET OF SUCCESS

What happens to a generation who gets the message that they have no wiggle room to mess up? Resilience, after all, is the act of getting up after a fall. “Failure, as any design firm will tell you, is the catalyst for innovation and discovery of new talents,” Dr. Ungar writes.

That’s not the lesson that young people appear to be learning. “A lot of the pressure students feel comes from a need to do well, and do well immediately,” says Ms. Burton, the student at Lethbridge. “Anytime I came home with a B instead of an A, I felt ashamed, even though I had plenty of other things to be proud of.”

Ross Denny-Jiles, a 26 year old in Vancouver, recalls how as early as Grade 9, he felt expected to know his future – he had high school friends, he says, already worried about getting into grad school. “We live in a competitive world and that is drilled into us all the time.”

The pressure to be the best in high school “consumed almost every aspect of my life,” says Mahima Mishra. The 21-year-old, now going into her third year of pharmacy at Memorial University in St. John’s, says she felt like she was “racing for a finish line that didn’t exist.”

Ms. Mishra isn’t alone. On mental health surveys, girls consistently report more stress than boys. Dr. Damour, who has a private practice and is the executive director of Laurel School’s Centre for Research on Girls, suggests one reason may be that girls worry more about disappointing the adults in their lives. She admits herself to using her “disappointed face” – named so by her daughters – to motivate them in school. “Though these interactions seem small, their impact is not.” They can foster an anxiety about failing, and a focus on results, not learning.

She suggests parents remind their kids that test results only reflect their knowledge of the material on a given day – so they learn the link between effort and outcome. Also a good idea, she says, is to help stressed-out students learn to identify when it will pay off to work harder, versus when it’s okay to let things go – to be more strategic about how they invest their time in homework and assignments.

In a section in her book called, “Swapping projectiles for pathways,” she advises parents to resist the “‘ballistics’ model of future success” – in which a child is launched like a rocket from high school, to a set of life-determining coordinates based on grades and activities. Instead, talk about success in terms of values and meaningful work.

In particular, she cites the positive example of parents who, when meeting with her, would focus on “who” – and not “what” – their two children would become as adults. They encouraged them to find work that they cared about and felt pride in doing. This was especially important since their daughters were very different – one was a typical high-achieving student headed for a top college, while the other was more artsy and just getting by academically. “They defined success in terms of pursuing wellbeing,” Dr. Damour observes, “not conventional markers of achievement.”

As Ms. Burton says, “If we put an emphasis on the entire journey, instead of minor events along the way, students could feel a lot better about themselves.”

University of British Columbia students wait to get their degrees at a fall convocation ceremony.Darryl Dyck/The Globe and Mail

BACK OFF, AND LISTEN

In The Stressed Years of Their Lives, American psychologist Janet Hibbs and psychiatrist Anthony Rostain point the finger with cutting precision: at parents who coddle, judge and demand too much. Their book, intended as a guide for parents to help their kids thought university, is peppered with anecdotes: A mother and father pushing university upon a son who doesn’t want to go, another couple who minimize their child’s mental health issue. In Toronto psychologist Sara Dimerman’s retelling in her book Don’t Leave, Please Go, her daughter begins to hint about not returning to university after a home visit; her mother coaches her firmly to see her first year through.

But most parents aren’t trained psychologists – and not every case is a mild bout of nerves and homesickness. In their book, Dr. Hibbs and Dr. Rostain advise parents to become informed of the signs of depression and anxiety, and to identify the services available at their child’s university before a problem happens. The best buffer to protect them from a mental health crisis, they write, are parents who give them a safe space to share what’s going on and where they can feel supported. Another important skill they emphasize also lines up with Dr. Ungar’s: “Parents can do their kids a favour by making it clear that openness to seeking help is a sign of maturity.”

After all, it’s seeking help that invariably saves young people when they find themselves in crisis. This was the case for Mr. Denny-Jiles, who dropped out of university in his second year in 2015, after struggling with depression. He attempted suicide twice. It was only after many thousands of dollars of therapy, covered by his parents, and medication, that he finds himself recovered today and about to start law school. While he doesn’t blame his depression solely on the pressure to succeed in high school, he says the burden to hit certain goals on cue was overwhelming – especially for an ambitious, perfectionistic student. In therapy, he says, he finally learned lessons that would have helped when he was younger - that “it’s okay to be sad, to take your time, that life is not a race.”

As he puts it, “We need to seriously re-evaluate the priorities and values that we impart to young people, because it’s destroying a lot of us. I did everything I was ‘supposed’ to do, and you know what? It wasn’t enough. My brain couldn’t accomplish what I thought was my mission.”

Ross Denny-Jiles, 26, dropped out of university in second year, battled depression and tried twice to kill himself. He says he learned in therapy that 'it's okay to be sad, to take your time, that life is not a race.'Darryl Dyck/The Globe and Mail

TEACH THEM TO SET THEIR OWN PRIORITIES

Changing that mission is also the topic of a new treatise by Danish psychologist Svend Brinkmann, entitled The Joy of Missing Out: The Art of Self-Restraint in an Age of Excess. Dr. Brinkmann makes the case for JOMO, not only as necessary to fix problems such as climate change and social inequity, but also for positive mental health. (This is, of course, in contrast to FOMO – the Fear Of Missing Out – which has only been heightened by all those trip-taking, high-achieving, like-seeking posts on social media.)

His prescription includes important lessons for our kids – learning to set personal goals not dictated by society, to think about what is truly valuable in your life and to find pleasure in focusing your energy there, even if it means missing out somewhere else. Time management is not about packing every hour of the day, but rather prioritizing activities that bring joy and a sense of achievement. He makes the case for moderation in all aspects of life – from what we buy to how we fill the day. Yet our environment, he says, tells us otherwise. Consumer society suggests every desire is legitimate, while social media suggests every want is necessary.

“All this makes it difficult to distinguish significant desires from insignificant ones,” he writes. If our kids – and, let’s face it, their parents - don’t feel they have to check off every box to be deemed successful, they have a better chance of finding a life that fulfills them.

Knowing what to care about is a lesson that Ms. Mishra only learned in university, after spending high school checking off those very boxes in sports, academics and student leadership. Now, she says, she sets her own expectations, and lets some things slide, to focus on what matters. Of her high school self, she observes, “I wish I could go back and just tell myself to breathe.”

The shared take away of all these books: to remind an anxious generation in their moment of stress, or facing failure, or uncertain about their future, that it’s healthy and smart to slow down, reflect on what’s important, and look for help. In other words, first, take a breath.

Erin Anderssen

Erin Anderssen