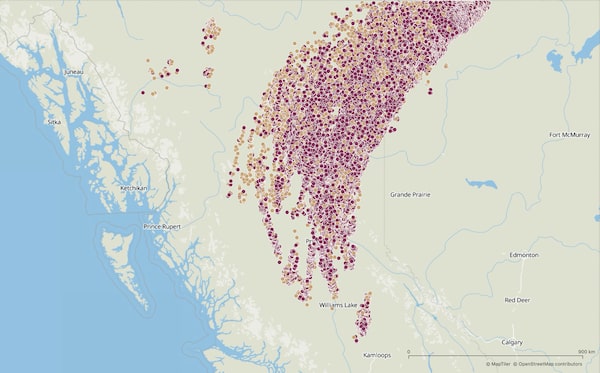

Lightning detected between June 30 and July 1: Purple dots represent in-cloud lightning; brown dots represent cloud-to-ground lightning.CHRIS VAGASKY/VAISALA

As wildfires scorched the earth in Western Canada this week, the skies were supercharged with hundreds of thousands of lightning flashes – a firestorm that climate scientists and meteorologists described as jaw-dropping and extreme.

Between Wednesday afternoon and Thursday morning, the North American Lightning Detection Network recorded a total of 710,117 lightning flashes across B.C. and northwestern Alberta. Of those, 597,314 were in-cloud pulses, meaning the lightning jumped from one part of a cloud to another, while the remaining 112,803 were lightning strikes that actually hit the ground.

Lytton, B.C., wildfire: At least two dead, as coroners head to region to investigate

The number of flashes detected in the 15-hour span represents roughly 5 per cent of the average annual lightning for Canada, according to Chris Vagasky, a Denver-based meteorologist with Finnish company Vaisala, which measures weather events, including lightning flashes, around the world. The activity seen this week in Western Canada, he said, is akin to what would be logged on a “big day” in a lightning-prone region such as Texas or Oklahoma.

“In a typical year, the United States has about 10 per cent of the world’s lightning and has about nine to 10 times more lightning than takes place in Canada,” Mr. Vagasky said. “So when you start getting United States-type lightning numbers in Canada, that’s a really big deal.” There was so much activity in such a short period of time that the tool he uses to track lightning kept reaching its download limit.

Several factors conspired to create the conditions for such a massive outbreak of lightning, Mr. Vagasky said: the recent record-smashing heat in the Pacific Northwest; a long-standing drought in the western third of North America; a summer storm system that developed in northern B.C.; and, most significantly, dozens of wildfires raging in the province.

The fires, he explained, effectively create their own weather systems. Wildfires burn at temperatures of roughly 800 C or more, which heats up the surrounding air. That superheated air rises into the cooler, more moist atmosphere, creating pyrocumulonimbus clouds above the fire.

“In those clouds, you have water and ice crystals, and you have smoke and particulates from the fire,” Mr. Vagasky said. “They’re all colliding against each other. It’s sort of like when you walk across the carpet in your socks in the wintertime and you get that static-charge buildup.” At a certain point, the cloud tries to neutralize itself, discharging electricity in the form of lightning.

This type of cloud is so ominous that NASA calls it the “fire-breathing dragon of clouds.” The space agency describes pyrocumulonimbus clouds like so: “A cumulonimbus without the ‘pyre’ part is imposing enough – a massive, anvil-shaped tower of power reaching eight kilometres high, hurling thunderbolts, wind and rain. Add smoke and fire to the mix, and you have pyrocumulonimbus, an explosive storm cloud actually created by the smoke and heat from fire, and which can ravage tens of thousands of acres.”

Scientists have long warned that a warming climate would increase the frequency and intensity of forest fires. The more forest fires there are, the more pyrocumulonimbus clouds and lightning events there will be. And the more lightning events there are, the more wildfires there will be. And so the cycle continues, Mr. Vagasky said.

Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at UCLA’s Institute of the Environment and Sustainability, said the recent bout of lightning in Western Canada almost assuredly sparked new fires. “I’ve watched a lot of wildfire-associated pyroconvective events during the satellite era, and I think this might be the singularly most extreme I’ve ever seen,” he said on Twitter. “This is a literal firestorm, producing thousands of lightning strikes and almost certainly countless new fires.”

As of Friday afternoon, there were 136 wildfires burning in B.C., nine of them considered fires “of note,” meaning they are highly visible or pose a potential threat to public safety. After breaking Canada’s heat record by reaching 49.6 C this week, the Fraser Canyon village of Lytton, B.C., lies in ruin. Evacuation orders have been issued in other parts of the province, including for neighbourhoods in Kamloops and Castlegar.

The North American Lightning Detection Network combines data from the National Lightning Detection Network in the U.S. and the Canadian Lightning Detection Network, Mr. Vagasky said. The networks use ground-based lightning sensors that listen for electromagnetic waves, which travel at the speed of light. These sensors cobble together all kinds of information, including the location and shape of the wave, to determine when the lightning occurred and whether it was in-cloud or cloud-to-ground.

Lightning safety, Mr. Vagasky said, begins with awareness. And there’s nothing like an outbreak of lightning and eye-catching satellite imagery of pyrocumulonimbus clouds to capture the average person’s attention. “The more people talk about lightning,” he said, “the more people who live in less lightning-prone regions will understand that it’s a potential risk to them and their property.”

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.

Kathryn Blaze Baum

Kathryn Blaze Baum