I’m standing at the corner of Jane and Finch, between the parking lot and Finch’s roaring four-lane expanse of asphalt. But in the distance I see a figure cruising along the sidewalk: a young woman on a bike. A minute later, a middle-aged man rolls past in the other direction, slowly and steadily.

“People are riding here, if you look for them,” said Darnel Harris, as a tanker truck growled past. “And there’s ample space to put some infrastructure that will accommodate them.”

Mr. Harris, who received a degree in planning from York University in 2015, would like to see more cyclists here on this car-centric corridor, getting people around and also carrying goods in so-called “cargo trikes.” He has proposed a route for these vehicles as part of the Finch West LRT being planned by Metrolinx.

And it deserves a serious look. Mr. Harris’s proposal is politically counterintuitive: In Toronto, cycling is seen as a largely downtown activity. Yet that framing excludes the hundreds of thousands of people in suburban Toronto who don’t have cars or even licences. And it ignores the reality that biking could be an ideal way to get around postwar neighbourhoods like those along Finch, if you make it safe and convenient.

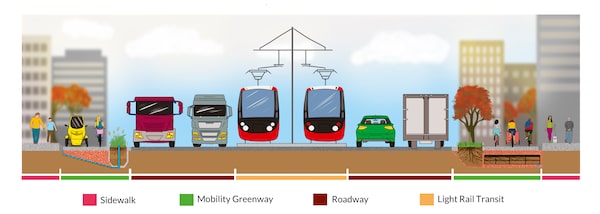

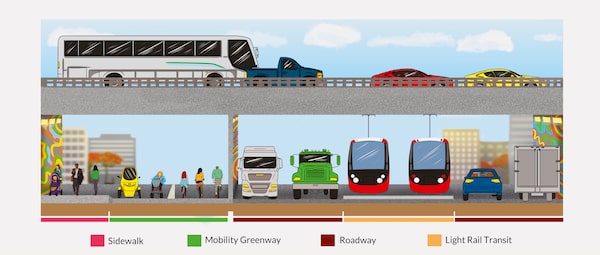

Darnel Harris’s Mobility Greenway proposal offers a different take on the Finch West LRT corridor.

This is where Mr. Harris’s proposal, which he calls the Mobility Greenway, comes in. His scheme would alter the design for the new LRT line that’s being planned along Finch West, adding a three-metre-wide lane that would encourage the use of active transportation to get people around nearby neighbourhoods, including York University, and even carry cargo.

If that sounds far-fetched, it shouldn’t. “This is not a discussion of bikes against cars,” Mr. Harris said. “It’s a question of what the appropriate type of vehicle is for a particular trip.”

Specifically, the proposal would allow the use of bikes, motorized scooters and motorized wheelchairs, and cargo trikes. Cargo trikes are three-wheeled bicycles with cargo compartments. They’re already in use in central Toronto by a distribution company called The Drop, and are being tested by UPS in Toronto; the UPS test vehicles can carry a payload of 400 kilograms, which includes the driver.

The current design for the Finch LRT corridor includes bike lanes, which are, Mr. Harris explains, inadequate. Cargo trikes and electric-assist velomobiles, like the Veemo are about 1.6 metres wide and would fill almost the entire lane. Mr. Harris’s proposal would fix that, as well as increasing the drainage capacity of the roadway by increasing its permeable surface, something that could make the project eligible for federal green-infrastructure funding.

Mr. Harris’s proposal would increase the drainage capacity of the roadway by increasing its permeable surface.

The city’s planning department recently passed a mass rezoning of tower neighbourhoods, including several that lie along Finch, designed to encourage retail and community uses in what are now all-residential areas. The ultimate goals of that policy include local entrepreneurship. In this respect, Mr. Harris’s plan dovetails nicely. What if a baker in one of the apartment towers north of Jane and Finch could send out lunches to customers at York University or a building a kilometre down the road – via a locally run bike-delivery service?

“It solves the goods- and people-movement challenges that lie at the heart of suburban vertical housing,” Mr. Harris said. “With a cargo trike, you can move from Jane and Finch to Kipling and Finch in 20 minutes or less, with half a ton of goods – no car needed. That trip would take a person driving 25 to 28 minutes during rush hour.”

“It will lower the costs of business in the northwest part of the city, and it will reduce traffic by keeping some people out of cars and off the road.”

His idea has the support of the local Duke Heights Business Improvement Area (BIA). “The biggest problem we have in this BIA is gridlock,” says executive director Matias de Dovitiis, “so for us, anything that can get people out of their single-occupancy vehicles is good. Bike lanes are one component.”

Will people in the area actually bike? The Finch West corridor “goes through some of the poorest neighbourhoods in the city of Toronto,” Mr. de Dovitiis said by way of an answer. “Add to that the fact that we have some of the most expensive transit tickets on the continent; add to that that some of these postal codes have the most expensive car insurance in Canada. It’s a question of affordability. If you build this infrastructure, people will use it.

Mr. Harris would like to see more cyclists here on car-centric Finch West LRT corridor.

Metrolinx “gave [Mr. Harris’s] ideas full consideration,” said spokesperson Anne Marie Aikins. “Many of his ideas weren’t feasible given other competing interests such as storm management and emergency services. However, the Finch project will have a number of similar design concepts,” she said, including 11 kilometres of multi-use path.

Yet Mr. Harris has not given up on changes being made to the design before the LRT begins construction; a dogged lobbyist for his vision, he has rounded up supportive statements from various politicians and local organizations, including local Liberal MP Judy Sgro and city councillors Maria Augimeri and Anthony Perruzza. Councillor Giorgio Mammolitti, on the other hand, has fumed publicly that Mr. Harris’s proposal would “take us back to a Third World country.”

That’s nonsense: Ask civic leaders in Denmark or the Netherlands whether bike infrastructure is compatible with an advanced economy. (It is.)

But Mr. Harris’s proposal, even if not implemented here, should inform how transportation and land-use planners look at the car-oriented suburbs in the region. Too often, “sprawl repair” is framed as a comprehensive task of remaking the entire landscape. “Assuming we don’t have trillions of dollars and decades to work with,” Mr. Harris says, “How do we work toward a better urban future? That begins with how you get places. You can’t necessarily walk everywhere, but you can get around on a wheeled vehicle. It doesn’t just have to be a car.”

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this story described the Veemo as the most common cargo trike. This version has been updated.

Alex Bozikovic

Alex Bozikovic