William Astor Drayton – a member of the New York Astor clan famous for mining, real estate, horses and taking up space in gossip columns – one day in the 1930s inspected the lilacs in his backyard in a smoking jacket. The jacket had a shawl collar, a button secured at the waist, and he dressed it up with a bow tie and pocket square.

Mr. Drayton's backyard was on his estate in the Kootenays, a mountainous slice of southeastern British Columbia defined by rough-and-tumble peaks rather than refined tailored suits. Mr. Drayton, then slim and balding, was a fancy-pants gold prospector in Fort Steele.

The Astor descendant lived how you would expect an aristocrat-in-the-bush to live: tennis courts, servants and a 5,000-square-foot log house with power, water, at least one Tiffany lamp, fieldstone fireplaces in five rooms and six gold-coloured sconces in the dining room.

Read more: Vancouver developer reloads an old war factory

Marcus Gee: Great Hall renovation shows Toronto is finally learning to appreciate its past

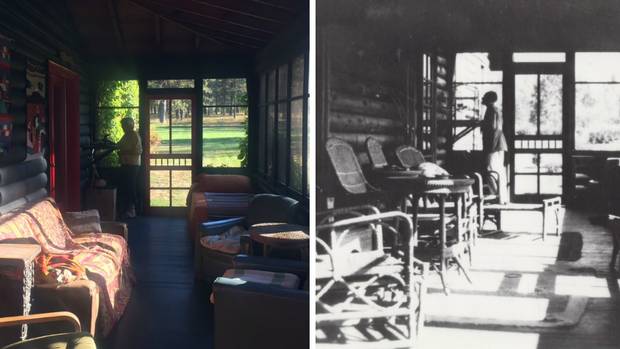

The Draytons' architectural and decorative legacy is still threaded throughout this 1929 home and its 20-hectare spread. And now the Wild Horse Farm is up for sale. The lilac bush where Mr. Drayton was once photographed is still here, albeit now joined by a 1,000-gallon propane tank to better heat the home. The porch is intact, wrapping around two sides of the building. Photos from then and now largely match. Antique light fixtures hang from clothed electrical cords – a selling point for potential buyers attracted to history and lore; a nightmare for those who favour low insurance rates and keeping up with building codes.

Astor House Drone photo of the Astor House. Photo credit: Christopher Gallagher

And that is what makes finding a buyer tricky. The market value for heritage properties is volatile. The grey wicker furniture on the porch is either quaint or kindling, depending on your attitude. The lights in the dining room's original wall sconces work, but the location of the switch is a mystery: Each bulb needs a quick twist in the sockets to turn on and off. Gardening – is it peaceful or a pain? Glaciers left behind a sand dune, another feature with debatable value.

Only two families have lived in the house since the Draytons. They, like the estate's founder, embraced the lifestyle.

"This really is the last day of summer, a beautiful one," Mr. Drayton wrote on Sept. 7, 1932, in a black journal now part of the University of Wyoming's American Heritage Center. "Our tennis tournament is a great success."

A document related to the Astor house.

'A grand old dame' of the Kootenays

Bob and Orma Termuende paid $400,000 in cash and stock (in one of their mining concerns) for the property in 1978, making an offer before ever poking their heads inside the house.

"It is like a grand old dame with rotten underwear," Ms. Termuende said in late September, accurately describing the home while simultaneously cracking wise about its unfinished basement. "We don't want to sell, but we would like to have somebody to take it over when we can't do it any more."

Ms. Termuende is 83; Mr. Termuende is 86. The couple's enthusiasm for cocktail hour, and the state of the property, with scores of gardens, tidy lawns, organized shops and sheds, mask their age. They want $2.5-million for the whole shebang.

"I think it deserves somebody like us," Mr. Termuende said after a morning of trading stocks, cooking breakfast for his wife and a guest, and touring the property and nearby historic sites. Their three children, however, do not want to inherit the work necessary to keep up the estate. Furthermore, the provincial government has twice passed on folding it into Fort Steele, now an old-time heritage town for tourists.

The property is 17 kilometres from Cranbrook, B.C., and roughly 400 from Calgary. It abuts the Wild Horse River, where kokanee salmon spawn in the fall. Water rights amounting to about 40 million U.S. gallons a year are included. Fort Steele's Diamond Jubilee Hospital, dating to 1897, is also part of the package and has been transformed into a rental home without decimating all of its historical features. Another Drayton-era cabin on the property hosts a tenant. The log buildings all match, painted brownish with red trim. There is a barn housing 12 stalls where the previous owner raised Appaloosa horses.

"There's a beautiful loft up there," Mr. Termuende said on his way to the building. "You could have a barn dance up there."

The property's history should be marketed with the same vigour as its tangible assets, says Mary-Ann Mears, Alberta's managing broker for Sotheby's International Realty Canada.

"There's value in that."

Lifestyle must also be priced in. Some potential buyers might want to pick raspberries in the morning and hike nearby Mount Fisher in the afternoon. Others would flee at the thought of bears raiding the apple trees and would rather go to the gym than the nearby ski hill.

The screened-in porch at the Astor home, pictured today and in the 1930s.

The Termuendes are not working with an agent; they expect the sale will be a private all-cash deal, given that the house would never pass an inspection with quirks like wiring installed around the time R.B. Bennett was prime minister. (On the flip side, Mr. Termuende believes the desk in his home office once belonged to that same Conservative leader.)

The previous owner's kitchen renovation blends Tex-Mex flare with a splash of Bavaria. The custom-built brick oven with a rotisserie inside is, again, either cause for a weekly pig roast or a feature to show friends but never figure out how to operate. (The kitchen and fireplace in the main living room – now coated with Tex-Mex white mud – are two features the Draytons would probably not recognize.) Antiques and artifacts from around the world pepper the home, though the purpose of some is unidentifiable.

Mr. Drayton brought worldliness to the Kootenays. Born in 1888, he served in the First World War as an artillery officer in the Royal Serbian Army, according to the New York Times. He then joined the Serbian delegation at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference and was part of the Bulgarian Atrocities Commission, the paper said.

He was poking around these parts in the 1920s, around the time New York papers were chronicling his first tawdry divorce. He paid $1 for property around Fort Steele, according to an indenture signed and dated March 19, 1929. At one point, Mr. Drayton literally owned the town. (It is unclear if the Wild Horse Farm was part of the $1 package.) In 1931, in Boston, he married Joan Bergere, an Australian musician and his second wife.

Bob Termuende on the porch next to a working Coke fridge from his wife’s father’s business. It’s now a beer fridge.

Carrie Tait/The Globe and Mail

"Mr. Drayton and his bride will go at once to British Columbia, where he has business interests, and where for a time they will make their home," the New York Times wrote on March 26, 1931.

But while gold may have pulled the prospector to the Kootenays, the Astors may have also pushed him away.

His mother's matrimonial choice and rumoured transgressions had transformed her from an Astor debutante in Manhattan to an Astor shame shipped to London for hiding. She is not mentioned in her wealthy father's will, the New York Times reported in 1892, but Mr. Drayton and his siblings inherited part of the Astor fortune. The New York Times documented his parents' divorce, rich with allegations of infidelity.

Mr. Drayton sold his Kootenay property in 1944. He died in 1973, at 85.

Now, the Termuendes are reluctantly preparing to leave their own heritage behind.

"When we started travelling, I felt we didn't really need to go top drawer, because we had top drawer at home," Ms. Termuende said.

Her husband joined in. "If you gave me – next week – the top floor of the Pan Pacific [hotel in Vancouver], with two butlers and a maid and three meals a day and everything that went with it, I wouldn't last a week.

"I'd rather be here, in the Kootenays."

The writer stayed as a guest at the Termuende home. The couple neither reviewed nor approved this article.