It has killed thousands across West Africa, spreading panic in the region and fuelling fears abroad of the contagion spreading by air travel and in hospitals. Here is what you need to know about the deadly Ebola virus and the measures taken to combat it.

What is it?

Ebola is a severe hemorrhagic fever that was first identified in 1976. Much is still unknown about its origin, but fruit bats are considered a likely transmitter of the virus, and it is introduced into humans by contact with or consumption of infected animals. It affects humans and non-human primates.

Where is it?

Earlier outbreaks have been contained or burned themselves out relatively quickly in defined areas of West Africa. This outbreak, the world's largest so far, is different, spreading unchecked thanks to unsanitary conditions and an initially tepid response to containing the virus in Guinea, where it was first detected in December, 2013.

The Ebola outbreak has hit hardest in the West African nations of Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. Cases have also been reported in Nigeria and Senegal, though both nations were declared Ebola-free on Oct. 19. Health-care workers in the United States and Spain who treated Ebola patients brought home for treatment have also been infected.

Facts: How does Ebola spread?

The virus is spread through direct contact (through broken skin or eyes, nose or mouth) with the bodily fluids of a sick person or animal or exposure to contaminated objects, such as needles.

Ebola viruses on dry surfaces such as doorknobs and countertops can survive for several hours; however, in body fluids, the virus can survive for several days at room temperature. The disease can be destroyed with disinfectants, such as household bleach, or by heating.

At least one major study suggests dogs can spread the virus, but it’s not yet known how likely it is that the pets of infected people can spread the virus to people. As a precaution, Spanish health authorities euthanized the dog of a nurse infected with Ebola.

Myths: How is it not spread?

- Ebola is not spread through the air.

- It is not transmitted through casual contact, such as sitting next to someone.

- The virus is only contagious if the person is experiencing active symptoms.

How to recognize Ebola

Symptoms of Ebola include:

- Fever (greater than 38.6 degrees Celsius or 101.5 Fahrenheit)

- Severe headache

- Muscle pain

- Weakness

- Diarrhea

- Vomiting

- Abdominal (stomach) pain

- Unexplained hemorrhage (bleeding or bruising)

Symptoms may appear anywhere from two to 21 days after exposure to Ebola, but the average is eight to 10 days.

How is it being treated?

The epidemic’s urgency has brought several vaccines and drug treatments into testing and active use on infected patients. The safety of these drugs for human use and their effectiveness in combating Ebola have not yet been fully tested. These include:

- VSV-EBOV: A potential vaccine developed by Public Health Agency of Canada scientists and licensed to an American company, NewLink Genetics of Ames, Iowa.

- TKM-Ebola: A drug developed by Tekmira Pharmaceuticals Corp., based in Burnaby, B.C., that attacks the virus’s genetic material.

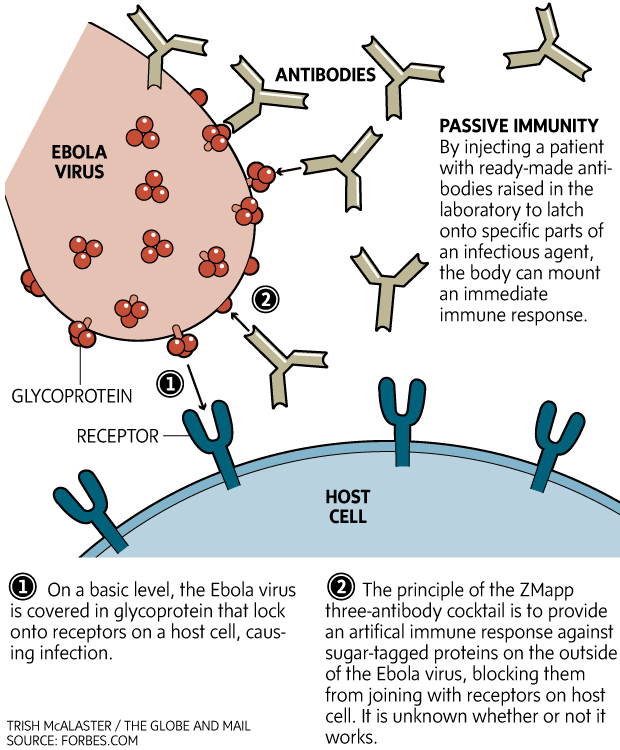

- ZMapp: An unlicensed drug cocktail, partly the result of Canadian research, consisting of three proteins intended to target the virus and prevent it from entering cells. (Read more about how ZMapp works)

- GSK’s vaccine: A potential vaccine developed by the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and GlaxoSmithKline.

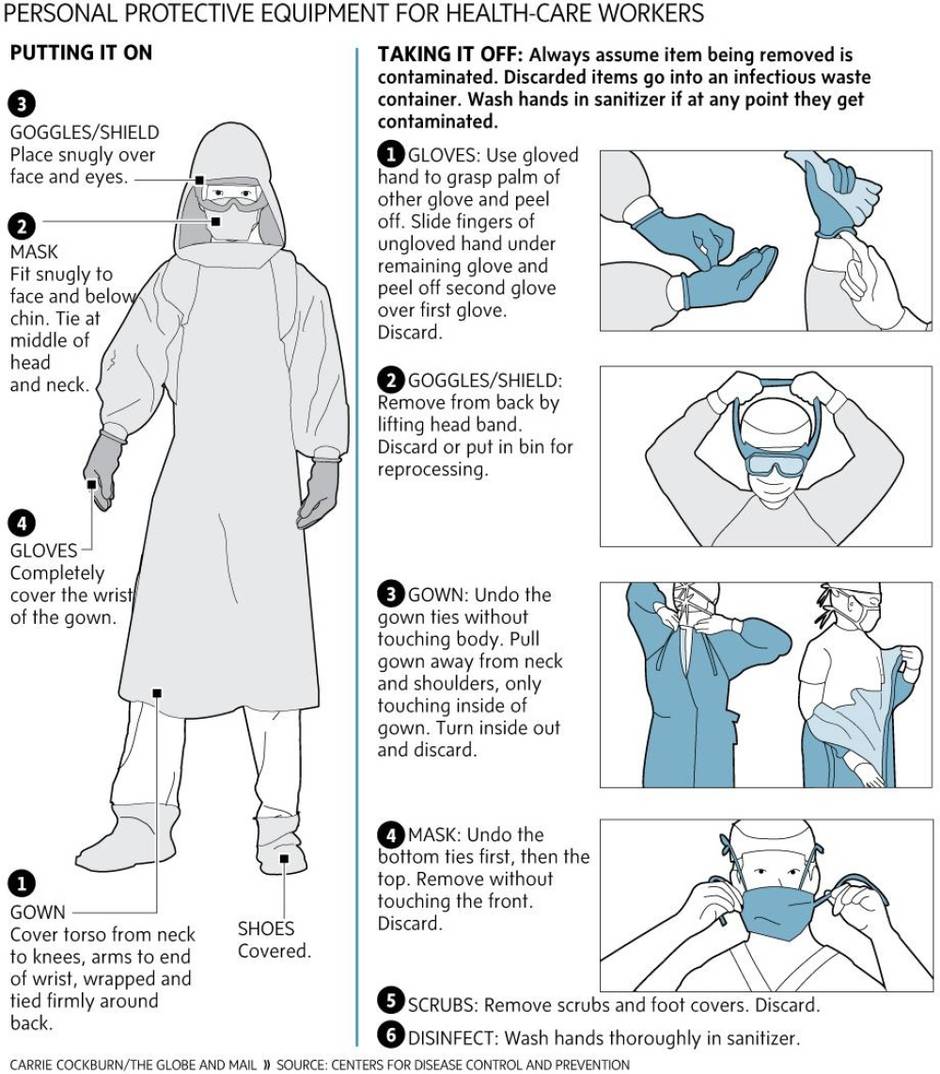

How are health workers staying safe?

Health-care workers treating Ebola need thorough protective measures to avoid catching the virus from their patients.

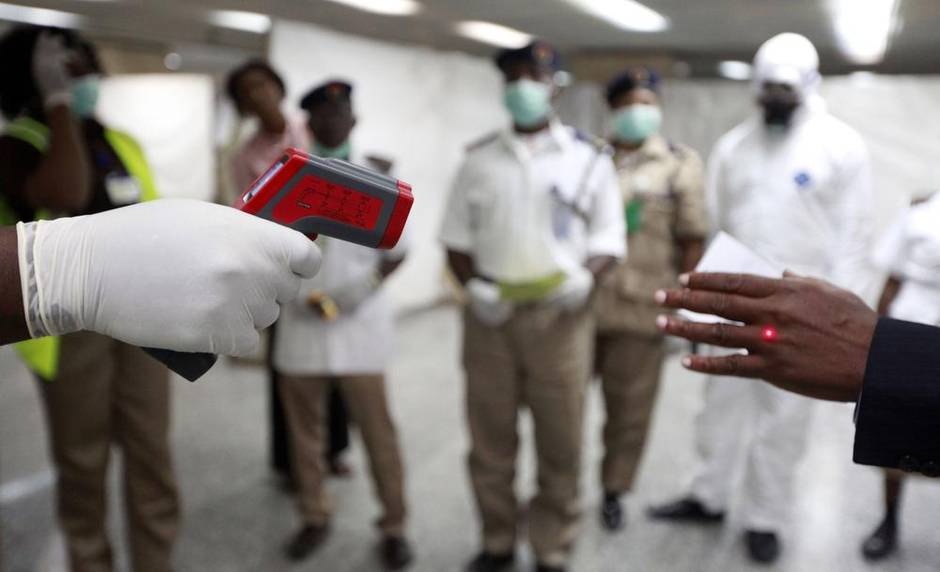

How has Ebola affected air travel?

Airports in West Africa and developed nations, including Canada, have introduced measures to screen passengers for fever and questionnaires asking about previous contact with the bodily fluids of Ebola-infected people. But the effectiveness of these screenings came into serious doubt when Thomas Eric Duncan, the first patient to be diagnosed with Ebola in the United States, travelled from Liberia without his infection, still in its early stages, being detected by a temperature screening.

Read more: André Picard on why you can’t stop Ebola at airports

Further reading

With reports from André Picard, Sean Tepper and wire services