ShevchenkoN/Getty Images/iStockphoto

Melissa Stasiuk is The Globe and Mail’s head of programming.

I was beginning to feel as sorry for the nurse as I felt for myself.

For the seventh month in a row, she was calling with my test results.

And for the seventh month in a row, she let out a long sigh, lowered her voice barely above a whisper and delivered what had become the familiar news: “Unfortunately, you are not pregnant.”

Well then. After six months of taking a pill to help me ovulate, one round of intrauterine insemination and 64 trips to the fertility clinic for blood work, ultrasounds and pained conversations with the nurses and doctor treating me, my husband, Chris, and I were faced with whether to move on to our last hope: In vitro fertilization (IVF), a physically and emotionally demanding procedure that involves injectable hormones and costs up to $30,000 for one round of treatment.

At 34, my biological clock was ticking, although my doctor tried to assure me that IVF success rates for women my age were about 40 per cent. Chris and I were desperate to try anything that could help us conceive, but we had a hard time reconciling $30,000 with odds less favourable than a coin flip.

But we had one thing in our favour: We live in Ontario, which provides funding that covers a large chunk of the cost.

The clinic, however, had more bad news: There was huge demand for this funding and a limited number of spots. They estimated the wait time at three to five years, meaning I’d be at least 37 to 39 years old, at which point our success rate could drop to 30-35 per cent – or less. Our doctor did not advise waiting.

This was one of many bumps along our “fertility journey” – a term popular with infertile couples who have gone through the hope and heartbreak of trying to have a baby – that took me to three clinics over the course of three years.

Along the way, I witnessed a lot of things that surprised me: a patchwork of services and fees at clinics, and a system that didn’t provide equal access to everyone (your wait time for funding could vary from three months to three years or more depending on the clinic you happened to be referred to). But I learned this, too: I was one of the lucky ones.

Ontario’s publicly funded system is the only one of its kind in Canada, and if things were frustrating for me, at least I didn’t live in Newfoundland, a province with no IVF clinic at all.

Ontario’s system costs the province $50-million a year. But that funding creates important standards that improve patient safety and saves the health-care system money. And it gives governments more of a say in how these private clinics operate, both now and as these technologies advance. It isn’t perfect, but it’s a model that the rest of the country should be looking at.

With infertility – a medical condition defined by the World Health Organization as a disease of the reproductive system – affecting one in six couples in Canada, access to treatment shouldn’t come down to luck of the postal code.

But I wasn’t thinking about any of this back in February, 2018, as we sat on a waitlist that would hinder more than help us and agonized over whether to ransack our savings or take out a loan to pay for IVF privately.

I just wanted to get pregnant.

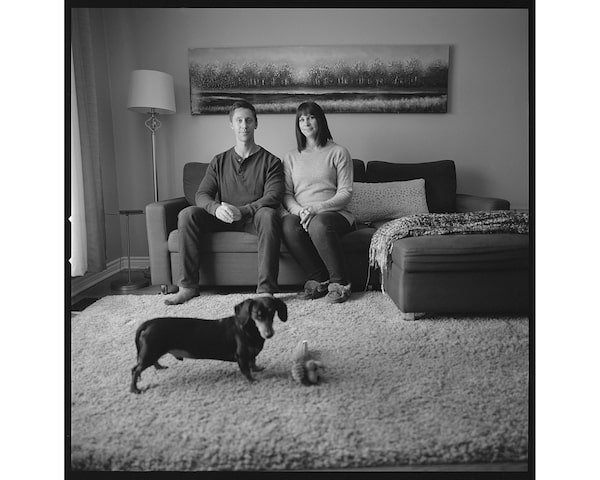

Melissa Stasiuk, husband Chris and dog Frankie at their Mississauga home. The Stasiuks turned to IVF after years of unsuccessful attempts to conceive.Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

For 17 years, my cellphone sounded an alarm daily at 8 p.m. It was my reminder to take my birth control pill, the soft ping ensuring I would remember to take it at the same time each day. This was key, I was told, to preventing an unwanted pregnancy. I thought I was being responsible.

Besides, there was lots of time to settle down and have kids. I should focus on getting an education, a good job, and the right partner before thinking about children. In fact, modern life demands it. Higher education leads to higher incomes. And having children at a younger age impedes your earning potential.

A recent study found that women who had their first child before the age of 25 earned a lower lifetime income of more than two years of annual labour income compared with women who were childless. And you’ll need that extra money if you ever want to own a home to put a family in. A recent report from non-profit Generation Squeeze estimates it will take us millennials 13 years to save for a down payment, and a lot longer if you choose real estate in Toronto or Vancouver. Renting is no easier, with city dwellers in the Greater Toronto Area and Greater Vancouver Area reporting that they spend up to 50 per cent of their income on rent and utilities.

We are bombarded with research and articles touting the benefits of more women in leadership positions. But climbing the corporate ladder takes time. Tech companies such as Apple, Facebook and Google have come up with what they see as a solution: female employees can freeze their eggs as part of their workplace benefits. This “perk” allows women to focus on their careers without worrying they are putting their chances of starting a family at risk.

And so, we delay. The average age of mothers at first birth has been rising steadily since the mid-1960s, when it was 24 years old. In 2016, the average age reached 29.2, Statistics Canada reports. More babies are born to women between the ages of 35 and 39 than women aged 20 to 24. Yet, a woman’s peak reproductive years are between her late teens and late 20s. By 30, fertility starts to decline, and by her mid-30s, fertility declines more quickly. (Male fertility declines with age, too, although generally not till 40 years old.)

If we agree that women earning an education, entering the work force and advancing in their careers is a good thing, then what help are we offering them when they follow this path only to discover they have done so by sacrificing their most fertile years?

The first sign of trouble came when I was 33 and I stopped taking my birth control pill shortly after Chris and I got married. I wanted to start tracking my cycle, so I could figure out the best time to try and get pregnant, but my periods were all over the place, with up to 60 days apart. My family doctor referred me to a fertility clinic, where at the end of a month of tests, I was diagnosed with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), a hormonal disorder and a common cause of infertility.

Infertility is not a rare disease. The causes vary, and include low sperm count or issues with sperm motility and a diminished ovarian reserve (which can be linked to a woman’s age). For some couples, infertility means frequent miscarriages. Sometimes the cause remains “unexplained.” But it can be treated.

For help, more couples are turning to IVF, a process that involves removing a woman’s eggs, fertilizing them with sperm outside the body, and transferring an embryo into the woman’s uterus in hopes it will implant and develop into a fetus. From 2013 to 2018, there was a nearly 40-per-cent increase in the number of IVF cycles initiated in Canada, according to data collected from fertility clinics by the Canadian Assisted Reproductive Technologies Register (CARTR). About 2 per cent of live births in Ontario result from IVF.

But in most of Canada, IVF – for many infertile couples the only viable treatment option, or the last resort after other treatments have failed – is available only to those wealthy enough to pay for it. The average cost of one cycle of IVF in Canada is $10,000 to $15,000. The required medications add about $5,000. Some clinics offer additional services such as genetic testing of embryos (an embryo that tests “genetically normal” could increase your chances of a successful pregnancy and reduce your chances of a miscarriage), which adds another $5,000 to $10,000 depending on the number of embryos you have to test. And this is if IVF works on the first try. If not, patients face the prospect and cost of trying again.

And IVF access varies greatly from province to province. Ontario, the only province with a funded IVF program, has 18 clinics that offer the treatment, most of which are in the GTA. Quebec has seven and, in the rest of Canada, there are 12, CARTR reports.

There is some financial help for fertility treatments if you live in Manitoba (a maximum $8,000 tax credit), in Quebec (through tax credits tied to your income level) and New Brunswick (through a one-time $5,000 grant). The federal government also offers a tax credit of up to 15 per cent. But these measures require couples to have the cash up front and often don’t push them far enough above the threshold where IVF becomes affordable. (In 2010, Quebec provided funding for up to three cycles of IVF but ended the program in 2015, citing high costs.)

Launched in December, 2015, Ontario’s program funds a large chunk of one cycle, but it is up to patients to cover the prescription costs (some are lucky enough to have this offset by a workplace insurance plan) and any additional services offered, such as genetic testing. Still, it is a lifeline for couples who otherwise couldn’t entertain the option. And with the exception of restricting funding to women who are younger than 43, it is inclusive: Sex, gender, sexual orientation or family status are not considerations in fertility treatment eligibility.

In B.C., advocacy group IVF4BC has been active in pushing for funding. Led by Nicole Nouch since 2015, the group’s efforts include letter-writing campaigns, presentations to politicians and a roundtable discussion that connected fertility doctors in the province with those in Ontario to learn about the program there. In 2018, the group’s request (one funded cycle for patients below a certain income and tax credits for the rest) was mentioned in the budget and some MLAs pushed for it, Ms. Nouch says. But it wasn’t approved, competing with higher priorities such as the opioid crisis.

In Alberta, Selma Scott, a fertility doctor at the Regional Fertility Program in Calgary, has been leading similar efforts in the province since 1984. Lobbying efforts there came close in 2015, when the government gave the two clinics in the province the go-ahead to set up a program that it promised to fund. But then the bottom of the oil patch fell out and everything was put on hold. "It’s awful to talk to people about the fact that you’re not going to have a family because you don’t have a certain income level,” Dr. Scott says.

Despite the challenges, figuring out funding is worth the struggle. Public funding addresses what Francesca Scala calls “reproductive justice” by increasing access across different races and classes. Without it, IVF tends to be accessible only to the privileged: “This is why sometimes infertility is dismissed as a white woman’s or rich woman’s problem,” says Dr. Scala, a professor at Concordia University who recently published Delivering Policy: The Contested Politics of Assisted Reproductive Technologies in Canada. “We typically associate IVF with these kinds of women because these are the patients we find in the waiting room.”

If more provinces offered publicly funded IVF, more doctors could be incentivized to open fertility clinics, knowing they would see a steady stream of patients who otherwise could not afford it, and in turn increase access to all types of fertility treatments.

A technician at Tenon Hospital in Paris selects eggs for in-vitro fertilization. In Canada, access to IVF clinics varies widely: Newfoundland and Labrador has none, while Ontario has 18, most in the GTA.Benoit Tessier/Reuters

Fertility treatments require frequent visits to a clinic, so your proximity to one is important. After my initial PCOS diagnosis, my doctor was hopeful that IVF would not be necessary. There were other options available. My first treatment, at a busy clinic in downtown Toronto, involved taking a pill called Letrozole, which helps with ovulation, combined with frequent monitoring through blood tests and ultrasounds, and timed intercourse. This is much less expensive (some costs were covered by OHIP and my workplace insurance plan) and less invasive than IVF. But it is no less exhausting.

I would arrive at the clinic between 7 and 8 a.m. on Day 3 of my cycle and wait among the dozens of other women there for my name to be called. Many days there were not enough chairs for the number of patients. Some days I would wait for an hour.

I barely made eye contact with the other women, let alone make conversation with them. Had they been trying to get pregnant longer than me? Would their experiences give me hope or make me more anxious? I couldn’t bear any comparisons and it seemed the feeling was mutual. Rows of us sat staring at our phones, the silence broken only by the nurse yelling out a patient’s name when it was her turn for blood work or an ultrasound.

After my turn, I went to work. On Day 12 of my cycle, I would be back in the clinic, daily, for the same routine monitoring, the doctor looking for the optimal time to recommend intercourse. This would take about a week.

The nurse would then call to tell Chris and me which days to have sex. Two weeks later, I would be back in the clinic for a pregnancy test and then wait for the dreaded phone call with my results.

Over the next seven months, I would visit the clinic 64 times. The seventh month we added Intrauterine Insemination (IUI) to our treatment plan to see if that would help. It didn’t. The constant cycle of needles and probes made me feel like some sort of human experiment. One that kept failing over and over again.

But in many ways, I was lucky. The clinic was close to my home and work. I could fit the frequent visits into my workday. What do women in Alberta or Nova Scotia do? Are they forced to take a leave of absence from work? How many couples could actually swing that? Do they forgo treatment altogether, their dreams of starting a family crushed?

At top, a medical technician at Tenon Hospital prepares embryo and sperm samples for freezing. At bottom, frost builds up on the pipes of the freezing equipment.Photos: Benoit Tessier/Reuters

The simple reason not to fund IVF is the high cost. Governments have to make choices about where to put their health care dollars. But asking someone to pay tens of thousands of dollars for IVF is not the same as asking someone to pay a few hundred dollars for glasses or a teeth cleaning.

IVF is a big ticket item, but publicly funding it could reduce the cost by virtue of scale, says Shawn Winsor, an ethicist at TRIO Fertility, a private clinic in Toronto.

“When you publicly fund something, it tends to generate research dollars from the government to examine that particular treatment or that particular health condition or even the drugs that go into treating that particular condition,” he says. “More money from non-industry sources means more non-industry research which potentially could lead to cheaper treatments or less expensive drugs.”

The research component is important, as we don’t know the long-term effects of fertility drugs or IVF procedures on the mothers or the babies, Concordia’s Dr. Scala says. Public funding could address this knowledge gap.

Public programs can also control costs by setting reasonable limits around who gets access and under what circumstances. While various factors determine IVF success rates, such as a patient’s age and whether genetic testing was done, they generally range from 30 per cent to 50 per cent. Is it cost-effective to fund a treatment with those odds? That’s where the importance of age restrictions and funding limits come in, to ensure governments are getting the most bang for their buck. Ontario has shown how these restrictions control costs. This is a lesson they heeded from Quebec.

Quebec’s IVF program was generous. From 2010 to 2015, couples in the province were eligible for up to three cycles of IVF. There was no cap on the number of patients who could access the program and there was no age limit. Essentially, anyone who wanted it could get it. And thousands did. From 2011-15, more than 35,000 funded IVF cycles were performed. In ending the program, the government cited costs of about $60-million a year. The province initially budgeted $30-million a year, greatly underestimating the demand. After the program ended, studies estimated IVF requests in the province went down by roughly 60 per cent – a drop that suggests thousands of infertile couples saw their dreams destroyed.

Ontario, on the other hand, limits its program to 6,000 cycles a year. It funds only one cycle per patient per lifetime, and only to those under 43, since IVF past that age is much less likely to succeed. Older mothers have a much higher chance of complications during pregnancy and birth, so restricting the age saves the health care system money, too.

This has made budgeting for the province more predictable. But not every patient is successful after one round of IVF, and the demand each year exceeds 6,000 cycles, which has resulted in long waiting lists that vary from clinic to clinic. It is better than nothing. But with the program now in its fourth year, it’s time to evaluate how it is doing and where it goes from here.

I was about to see for myself how unfair the waitlists can be.

An obstetrics room at Tenon Hospital. Ontario allows only one cycle of funded IVF per patient, and limits that funding to 6,000 cycles provincewide each year.PHILIPPE LOPEZ/AFP/Getty Images

After seven rounds of failed fertility treatments, we decided we needed a break.

I was becoming overwhelmed by feelings of inadequacy. Why was I failing at what people call "the most natural thing in the world”? I limited my time on Instagram, which seemed to become an endless scroll of pregnancy announcements, gender reveals, baby showers and births – all a painful reminder of my broken reproductive system.

Friends and family tried to be reassuring: “Just relax!” As if more yoga or massages would magically melt our stress away. “Stay positive.” Everyone had a story about a friend of a friend who got pregnant once they stopped trying so hard. Or my personal favourite: “Enjoy all that sex!” As if doing it on command was something to look forward to. I assure you, it gets old fast.

During this time, we moved to Mississauga, where we bought a house, thinking it would be a great place to raise a family.

The move made our failed treatments even more stinging. The space we had envisioned as a baby room sat empty for the next two years.

We found a clinic closer to our new home and did another month of monitoring to see if anything had changed. I had started seeing a naturopath, who recommended some supplements and lifestyle changes such as cutting out bread and limiting alcohol – two of the few comforts I had left – in an effort to naturally “rebalance” my hormones. I added in “fertility acupuncture,” which is supposed to help with this rebalancing, too.

But nothing had changed. I was still broken. Our new doctor agreed that IVF was our best option, but the waitlist for funding remained the same: three to five years.

In what felt like another streak of bad luck, our doctor was recruited to teach; a new doctor, associated with a new clinic, would be taking over the practice.

After a few months waiting for an appointment, we met with the new doctor to discuss IVF. She had some surprising news: with her clinic, the wait for funding was just four months.

A wave of emotions washed over me: elation that we would be able to afford IVF, and anger. If my “fertility journey” had taken me to a different clinic in the first place, would I have had IVF by now?

A Polish doctor injects sperm into an egg during an in-vitro procedure called intracytoplasmic sperm injection.Kacper Pempel/Reuters

As promising as Ontario’s publicly funded system is, its biggest flaw is the drastic difference in waitlists. Ontario allocates funding to each clinic based on factors such as the volume of patients they treat, and each clinic is responsible for determining who is eligible for that funding and how they manage their waitlists. A survey of Ontario clinics found some manage their lists on a first-come, first-served basis. Some use a lottery. Others use factors such as a patient’s age or how long they’ve been at a clinic. So some IVF patients wait months for funded treatment, while others wait years. If patients choose to pay privately, they get treatment right away.

Nothing about how the waitlists work was disclosed to me or posted on the websites of any of the clinics I visited. I only found out after I happened to move, and after talking to others I knew who were seeking IVF.

My sister and her husband sought IVF (for a different reason than mine) at a different clinic in downtown Toronto. They waited just three months for the funded procedure and gave birth to a healthy baby girl in August. One friend who went to a clinic in Markham, Ont., waited 10 months for funded IVF. Another in Hamilton was told it was a one-to-two-year wait. At 35 years old, she opted to pay for the treatment in full so she could get it right away.

And the differences among clinics don’t end with the waitlists. The services offered and fees required also vary. My clinic, for example, offers genetic testing of embryos. My sister’s clinic required that she and her husband attend an in-house counselling session at an additional cost in order to qualify for IVF, which doesn’t sound like a bad thing. But when you’re facing thousands of dollars in bills, another $500 can hurt.

Publicly posting waitlists and fees would be a huge help to patients. Instead, they are forced to rely on whisper networks – if they are lucky enough to find out at all. These inconsistencies among clinics encourage patients to shop around, potentially holding spots on multiple waitlists until one works in their favour. This wastes the time of doctors and their staff, as well as resources, and creates a backlog on a system already strained by demand.

Mr. Winsor, the ethicist, who led a study of the impact of Ontario’s funded IVF program, says it’s an iterative process. He expects to see better standards and more regulation in the future.

Better data would be a good place to start. In Ontario, IVF clinics voluntarily report data to CARTR, the national registry, but you would have to know where to look to find it. As a patient, I was desperate for a sense of success rates from an unbiased source. CARTR has this info and so much more. Why not share it?

Of course, it depends how you define what success looks like in the first place.

For patients, pregnancy rate isn’t the greatest indicator of success, says Mr. Winsor, who points to other factors such as the birth of a healthy baby as a better measure. “But for a clinic, their goal is to get people pregnant. So that’s how they measure it. One thing a publicly funded program can do is outline clear, valuative metrics that are more reflective of what the public are looking for, like a healthy baby.”

In the survey he conducted, people had a lot to say about the waitlists.

“The common response, even within the industry among clinicians, is the feeling that the government probably should have created its own standardized wait list much like they do with organ donation.” Ontario manages the wait list for organ donors through its agency, the Trillium Gift of Life Network, whose mandate is to ensure eligible Ontarians have equal access. They use standardized processes with input from specialists in the field. In other words, the Ontario government already has expertise in developing, implementing and managing waitlists for health-care services, so why not apply this expertise to the IVF wait list?

London's Science Museum displays some of the equipment needed for one cycle of IVF at a 2018 exhibit marking 40 years since the birth of the world's first in-vitro baby.DANIEL LEAL-OLIVAS/AFP/Getty Images

If my previous rounds of fertility treatment made me feel like an experiment, now I was a full-blown research project.

At 8 p.m. each day over the course of nearly two weeks, I laid out my lab equipment: one pre-mixed vial that looked like a pen that I clicked to select the proper dose before attaching a needle; one vial of medication with one vial of saline that I measured and mixed before loading into a syringe and attaching a needle; another syringe already conveniently loaded with medication and a needle (why didn’t they all come like this?!); a few alcohol swabs; and a needle-disposal box.

The first time, it took me 30 minutes to work up the courage to pinch my stomach (two finger-widths from the belly button, being sure to rotate sides each day) and guide the needles one after the other through my skin (not too fast but not too slow either).

The medication needed to be refrigerated and had to be done at the same time each day for 12 days, which for me happened to fall on the night of a friend’s wedding. A bathroom stall does not lend itself to IVF medication routines and I wasn’t about to ask the bartender if I could take up some fridge space. So during dinner I hopped in an Uber to my office where I could use a private bathroom.

When I pulled back up to the wedding (I had the whole needle routine down to 10 minutes flat by then!), two of my husbands’ friends who I had just met earlier that night happened to be standing outside. There was no way around the awkward explanation so I told them where I had been and why. It turned out that one of them had a one-year-old son who was conceived through IVF. She spent the rest of the night preparing me for what was to come.

And it was a lot.

After the medication got me to a level my doctor was happy with, it was time for my egg retrieval. Chris drove us to the hospital that morning and he was taken to a room to deposit his sperm. I was brought into another room where they would collect as many of my eggs as they could with a probe and needle through my uterus. It’s not a pleasant procedure and despite the pain medication, it still felt like someone was scraping around inside me. But it only took 15 minutes, after which the doctor excitedly yelled out my egg count (22!). I was taken back to a waiting area, where, feeling woozy from the medication, I threw up and fainted. I was sore with every step, and the medication gave me bloating so uncomfortable my pants barely fit. That discomfort would persist for two weeks.

The next day, the embryologist called to let us know how many eggs had survived fertilization: 15. After six days, they called again: 10 embryos remained.

We opted to pay for genetic testing, which is priced based on the number of embryos you have (10 embryos cost $6,000). We had been through nearly three years of treatments and waitlists at this point.

If there was something that could increase our chances of success or provide us more information, we were ready to take it. The public funding made this choice possible for us. We swallowed the giant lump in our throats and crossed our fingers.

The testing left us with four genetically normal embryos, results that both we and our doctor were pleased with. Surely at least one in four would work.

A multi-celled human embryo in cryogenic storage. In many jurisdictions with pubicly funded IVF, patients can have only one embryo transferred at a time.Bourn Hall Fertility Clinic, Findlay Kember/The Associated Press

Another lesson Ontario took from Quebec’s program – and a standard of several funded IVF programs around the world – is the single-embryo transfer policy.

Transferring more than one embryo at a time can increase the chance of a successful pregnancy (more embryos mean more chances that one will implant). But it also increases the chance of multiple births, such as twins or triplets (if more than one of the embryos implant).

Multiple births put both mother and babies at higher risk of complications and come with a higher cost to the health-care system since they have a greater chance of being born premature and having long-term health issues.

The single embryo transfer policy has greatly reduced the number of multiple births from IVF in Ontario (where they account for 5.9 per cent) and Quebec (4.6 per cent), compared with the rest of Canada (11 per cent), 2017 data from CARTR show.

Reducing multiples saves the health-care system money: In Ontario, for example, the average cost of a single-baby birth is $2,326 compared with $12,486 for multiple births, according to the Canadian Institute for Health Information for 2017-2018.

Public funding also reduces demand from patients for multiple embryos. When patients are not influenced by financial considerations, they no longer feel the pressure to opt for multiple embryo transfers in the hopes of achieving a successful pregnancy, Dr. Scala argues. If you are spending tens of thousands out of pocket, you are much more tempted to maximize your chances of success.

Data from CARTR back this up. The number of double embryo transfers is much lower in Ontario. For patients between the ages of 35 to 39, for example, 33 per cent had a double embryo transfer in 2018 compared with 51 per cent for patients in that age group in the rest of Canada.

In addition to setting standards of care, public funding gives government, and therefore patients, a better window into a private industry.

“The industry is very secretive,” Mr. Winsor says. Believing that clinics use proprietary techniques that lead to better success rates, they have been hesitant to share knowledge.

Public funding can help reduce this secrecy, he says, leading to consistent standards and better and more consistent information for patients. This becomes even more important as the technology used in IVF, such as genetic testing, advances.

Currently, patients who pay for it are only told whether the embryo is “genetically normal." But researchers are looking at how it could be used to determine traits such as height, eye colour and even intelligence.

“Once we are able to do it, people will choose it, undoubtedly,” Mr. Winsor says.

Trevor Mallard, House Speaker of New Zealand's legislature, cradles the baby of fellow MP Tamati Coffey at a 2019 parliamentary debate. Mr. Coffey and his husband had the baby with help from IVF and a surrogate.Parliament TV via AP

If Ontario turned to Quebec for lessons from the past, it may look to New Zealand when charting the program’s future.

Since 1999, New Zealand has determined eligibility for IVF funding through a rigorous clinical assessment that scores patients on a wide range of factors, including whether they smoke, their Body Mass Index, whether they have children, and their chance of pregnancy with or without treatment. Patients must score at least 65 out of 100 to qualify.

The assessment aims to optimize for success, eschewing a one-size-fits-all approach when allocating funding. Funding covers up to two cycles of IVF treatment, including medications.

This approach would need to be weighed against how it would affect waitlists. (In New Zealand, they are about one year.) But it would standardize how patients receive funding and could boost success rates while still maintaining a financially sustainable program.

Nearly every EU country offers some form of state-funded fertility program, with Denmark’s among the most generous at up to six cycles covered. (As a result, about 4 per cent of Denmark’s births are a result of fertility treatments.) In the United States, a few states offer some coverage through health insurance and patients can apply for grants from different organizations depending on where they live and if they meet certain criteria.

Meanwhile B.C., a province with a population almost as big as Denmark’s, can’t come up with any funding at all.

Ms. Stasiuk holds ultrasound photos of her baby.Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

Two weeks after my IVF embryo implantation, my phone rang. It was the nurse calling with my results. This time, the voice sounded cheery and eager to deliver the news.

“Congratulations, you are pregnant!”

I let out a gasp and blurted out: “Are you sure?”

It was hard to believe that it finally happened. All those pills, needles, tests and tears were worth it.

I’m due in April and though I can’t wait to meet our baby, I still feel a pang of guilt at the thought that other couples struggling with infertility may not get the same chance.

Of course IVF is not successful for everyone. We went into it thinking that even if it didn’t work, we would find comfort in knowing we had exhausted all options. It would have allowed us peace.

Canadians outside of Ontario deserve the same. Couples experiencing infertility are suffering from a medical condition, not a lifestyle choice. Medical treatment is necessary and has been shown to work in many cases. Families are the pillars of our communities and supporting their growth and health is crucial to a thriving society. The time for provinces to recognize this is long overdue.

Quebec Premier François Legault vowed during the province’s election campaign to restore one cycle of IVF funding per patient by 2020. Will he follow through on his promise?

Ms. Nouch of IVF4BC remains hard at work. As an executive for the BC Liberals in her riding, she aims to have the funding proposal discussed at the party’s convention in September and part of the party’s platform in the next election. Will the government there finally step up?

After 43 years of practise, Dr. Scott of Alberta plans to retire soon; the clinic doesn’t currently plan to replace her. What will the province do to ensure care doesn’t become even more strained?

If the provinces won’t act, the federal government doesn’t need to stay silent. It has the ability to increase its tax credit and it can incentivize provinces to set up funded programs.

Infertility is accompanied by intense feelings of shame and there is a lot of misunderstanding about the disease. Public funding would go a long way toward easing that by showing affected women and men that it’s not their fault, that they are deserving of help. Most importantly, that they are deserving of hope.

Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

Keep your Opinions sharp and informed. Get the Opinion newsletter. Sign up today.

Melissa Stasiuk

Melissa Stasiuk