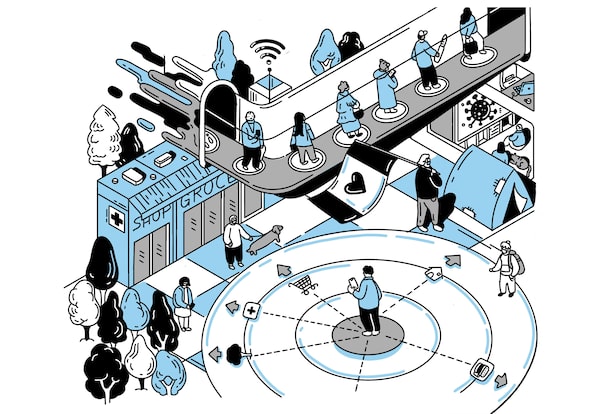

Illustrations by Kathleen Fu

The flourishing of sidewalk dining, bicycle lanes and car-free roads in the summer months; the almost vacant, carefully cleansed public squares and boulevards in the lockdowns of March and November; the new tolerance of youthful life that’s exploded in the parks; the careful and sanitary new world of public transit. In an instant, cities and their governments have changed a lot of things that had for generations seemed fixed and unchangeable. Some of it was on a temporary, emergency basis, though many of those changes, out of popularity or practicality, are sure to stay.

Less visible are the deeper, more lasting changes provoked by the pandemic – major transformations that will last beyond vaccination and recovery.

Some mayors and city councils have turned this global crisis into an opportunity to be seized, a chance to do things they had long desired but only imagined.

Just listen to the mayor of Lisbon.

“As soon as we saw that this virus is not a thing that is going away quickly, we thought, ‘Okay, we have here a problem, we have here a new reality, so how in this new reality can we push forward our agenda?’ And we saw that we have some opportunities we could go with,” Fernando Medina, now in his fifth year as mayor of Portugal’s capital, said in a phone interview.

Mayor Fernando Medina, right, poses with Antonio Melo, 72, after handling him the keys of his new apartment in one of Lisbon's historic neighbourhoods in 2018.PATRICIA DE MELO MOREIRA/AFP/Getty Images

When the COVID-19 pandemic first locked down his city in early March, Mr. Medina watched a series of crises magnify. Lisbon’s crucial tourism industry immediately collapsed, and with it the livelihoods of the 20,000 residents who’d built short-term rental flats for services such as Airbnb. Their income, and the city’s business-tax revenue, were lost.

At the same time, the city’s housing crisis became deadly. Every week, thousands of workers came to Lisbon from the rural periphery to work in essential service jobs – teachers, cleaners, couriers – typically staying in dormitories, or riding on buses, that became infection vectors. The city, scarred for years by the 2008 economic crisis, had not been able to get enough lower-cost housing built quickly enough.

Over the summer, Mr. Medina found a way to combine those problems in a single solution.

The city snapped up thousands of the short-term rental flats on long leases, and turned them into subsidized housing for the crucial workers under a program called “Safe Rent.” Chosen through a lottery system with a preference for young and lower-middle-class employed people who wouldn’t normally be able to afford to live in the city, the rents were capped at a third of the workers’ net income. The flat-owning residents were saved from ruin, the workers were able to live in the same city where they worked at reasonable rent, the city collected its taxes from both, the tourism-dominated neighbourhoods gained thousands of long-term residents and a greater sense of community – and all done far, far faster than it would take to build new housing units. The total cost of the long-term leases minus the rent received comes to about €4,000 ($6,200) a house, lower than the price of building housing units – and an amount that Portugal’s national government has been eager to provide for thousands of houses.

“We realized when the crisis hit, that we could at the same time solve, with this initiative, three goals – it raised quickly the number of houses available to the young and middle classes; it helped the incomes of the owners of the houses that were in the short-term rental sector, and it developed neighbourhoods that were suffering, helping to create a more sustainable city,” Mr. Medina said. “This is now a new lane in our housing policy – the government passed a law to create tax benefits for people to make their homes part of this program. It’s something we’ll keep doing, and the government is encouraging other cities in Portugal to adopt our idea.”

If Lisbon turned crisis into opportunity, other cities have been forced by circumstance to change the way they function, in lasting ways.

In Victoria, Mayor Lisa Helps found herself, during the early months of the pandemic, in an ugly confrontation with hundreds of residents over two of the city’s most noticeable features – its beloved parks, and its population of street people.

When the coronavirus came to B.C., its homeless shelters and treatment centres were forced to halve their populations overnight in order to maintain distancing. At the same time, a less-troubled group of couch-surfers and room-sharers were also forced outdoors by infection-wary hosts. As in many other Canadian cities, Victoria’s parks developed clusters of tents; Ms. Helps ended up apologizing after her attempts to organize a serviced tent city in a park led to ugly clashes with neighbourhood residents.

Over the summer, she created a new kind of organization, the Decampment Working Group (it is part of an existing group called the Community Wellness Alliance). Bringing together top leaders from the city, its business organizations and chamber of commerce, provincial health and housing departments, charities and Indigenous organizations, its goal was to put a roof over the heads of at least 80 per cent of the people living in parks (estimated at 250 people), on a person-by-person basis, by the end of 2020. Different sorts of people would get different sorts of housing – a room in a new shelter with support services for the terminally homeless, leased motel spaces for others, donated private rooms with subsidies for more hopeful cases.

“It’s a new way of working together,” Ms. Helps told me. “It’s deeply collaborative and there’s no finger-pointing … the collaboration between the health authority and BC Housing is unprecedented … . These relationships and new ways of working have solidified – we won’t be able to turn back, and I think that’s a good thing. It’s not going anywhere."

It’s still an incomplete project, and it remains to be seen if the long-term park dwellers can be housed and sheltered by winter. But it’s also a telling example of the way the pandemic has changed the thinking of urban leaders, and forced them to forge new institutions that are likely more effective, and lasting, than the old bureaucracies.

Tents for homelss people stand beside Victoria's City Hall this past June.Chad Hipolito/The Globe and Mail

Lisbon and Victoria are certainly not the only cities to have discovered that their affordable-housing systems and homeless shelters are so poorly designed and overcrowded that they were in danger of becoming major disease transmission vectors. In fact, the highest rates of COVID-19 infection in most North American and European cities has generally been found in social-housing and low-rent private apartment districts in the inner suburbs. This has led to large-scale emergency investments in housing upgrading – often by redirecting infrastructure funds – in many cities. This has changed housing-department approaches and priorities, often for good.

According to Lamia Kamal-Chaoui, director of the department devoted to cities, regions and small business at the Paris-based Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, it was local governments that led the way in devising new techniques and institutions during the first months of this pandemic. Though national governments were generally providing the funds, they were typically too slow-moving and disconnected to make that flood of money do things on the ground. “In the beginning of the pandemic, mayors became the essential workers – they were dealing directly with the public,” Ms. Kamal-Chaoui said in an interview. “The difference between cities and national governments is that many of those mayors have been super pro-active, they have been innovative. From early on, they have started to think of the aftermath, so they have taken some actions that to a certain extent we can expect to be permanent.”

Ms. Kamal-Chaoui’s OECD department has kept tabs on the policy changes being made in hundreds of cities around the world in response to the pandemic, and tracked them in a series of reports. At first, most of the new policies were hasty and improvised emergency measures designed to protect lives and livelihoods as the coronavirus seeped into the city, along with emergency funds from higher levels of government. By the time the OECD had issued its second report on policy changes in late July, however, many new policies and institutions had become more or less permanent features.

That includes a lot of those highly visible changes to streets, sidewalks, dining spaces, bicycle lanes and parks – many of which were considered temporary lockdown measures to enable safe distancing, but proved so popular with residents that some have become permanent. Long-established driving spaces such as Berlin’s Friedrichstrasse and Athens’s Omonia Square, along with dozens of kilometres of streets in cities such as Bogota and Milan, have changed more or less permanently into spaces for pedestrians and cyclists.

A cyclist makes his way down a two-way cycling lane in Berlin's Friedrichstrasse on Sept. 8. A length of the central street has been closed to vehicle traffic.JOHN MACDOUGALL/AFP via Getty Images

Less visible but equally important are the dramatic changes to the data traffic within cities. The sudden shift last spring to remote work and schooling led to hasty improvisation by cities and school boards to make this possible. Some, such as Tokyo, built entire e-learning platforms – virtual school boards – so that schools could move online (by contrast, North American cities generally relied on a patchwork quilt of commercial products). In Istanbul, where at least a quarter of families have no access to internet, the city deployed a new distance-learning system that combines access points and TV channels, as well as some of the first digital technology to be installed in many schools.

Simply ensuring that everyone in a city has some minimum level of viable internet access proved a large-scale change. In wealthier countries such as Canada, many low-income families have only a smartphone as their shared source of internet access. Others use public libraries as their sole gateway to online life – and when the pandemic shut the libraries down, they lost their access to work and school. Some libraries pointed their internet access points outward to the streets, and many cities began developing municipal WiFi schemes that are certain to become permanent fixtures.

Some of these changes have taken cities by surprise, mutating from impromptu jury-rig innovations into lasting fixtures as people get used to them. But in many cases, they are things that mayors, councils, municipal officials or citizens have long wanted to do, but had been considered unworkable owing to lack of financing, bureaucratic immobility, or lack of political will from the higher levels of government that tend to control the fates of cities.

These longer-term changes have generally been easier to contemplate in European cities, which tend to be directly funded by national governments. In North America, where the property and business tax revenues that fund a bigger share of their budgets haven taken a hit in this pandemic, it has been slower going – and, should the emergency funds dry up, some of those potentially “permanent” changes could be in jeopardy.

But the forces behind these waves of creative destruction aren’t only driven by money. Measures of public trust in government, taken by organizations such as Edelman, show an “unprecedented” rise to record-high levels.

This suggests that more cities could use the upside-down world of a pandemic emergency to make other major permanent reforms – in service delivery, education, transportation and ecological sustainability.

“So many cities are in this type of situation today where they can do a lot of things, and they are seizing the opportunity,” says Ms. Kamal-Chaoui. “I don’t think that opportunity is going to last forever. And I think the next crisis will be the social one, the jobs one, and it will need similar new thinking.”

That puts extra weight on city administrations that might not have been so farsighted during the past six months of crisis – their citizens have learned that it’s possible to make fast and substantial changes to important aspects of urban life, and now expect them to respond similarly to other looming crises.

David Miller, shown in 2010, is a former mayor of Toronto.JENNIFER ROBERTS/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

“I think what COVID has done is create an environment where people are prepared to accept creativity and innovation, but they also want collective problems addressed," said David Miller, the former Toronto mayor and an environmental-organization leader. “They’re not going to stand for discussion of it. They’ve seen in COVID that we did it, and they’re going to expect the same kind of thing on climate.”

Mr. Miller, currently North American director of the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group, recently published Solved: How the World’s Great Cities are Fixing the Climate Crisis, and in researching that book in the early days of the pandemic, he found that the crisis and its new economic circumstances were providing many cities that opportunity to introduce green and emission-reduction policies that had previously been difficult.

For one thing, city-dwellers developed a new appreciation for natural spaces within their cities – not just as splashes of green amid the asphalt, but as refuges to be used on a daily basis. He points to cities such as Medellin, Colombia, and Freetown, Sierra Leone, that have used the pandemic crisis as an opportunity to plant hundreds of thousands of trees.

Likewise, he says, neighbourhoods have become much more important – not just as bedroom clusters, but now also as daylong working spaces. Their residents have demanded changes already. Local grocery stores have added delivery service and people have become acutely aware of missing services and shops in residential areas where zoning has prevented them from easily setting up shop.

These neighbourhood-level transformations – provoked by work-from-home and remote education practices that many say will become at least partly permanent – are the area where almost everyone agrees that cities will need to make the most dramatic and permanent changes. Some office districts might need to be rezoned for, and reconstituted as, housing districts. Bedroom neighbourhoods might need to become all-day, full-service neighbourhoods, where types of shops and services might have to be encouraged that planning rules had previously forbidden. And the ability to work remotely might drive entire populations out of the city permanently, and new populations into it.

The problem, though, is that nobody really knows how these new ways of working and learning, and new attitudes provoked by a long period of isolation and quarantine, will shape urban life and, therefore, long-term policies. There’s a lot of speculation, and little substance to work on.

Some city leaders have let this prospect of a bold and frightening postpandemic world give their existing policy ambitions a push. Many mayors have taken inspiration from Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo, who saw her fortunes reverse abruptly during the pandemic. Her bold transportation and housing plans had become unpopular in France in early 2020 – especially her notion of the “15-minute city,” a vision of compact and walkable neighbourhoods that critics say appeals to the already fortunate central-city elite and does little for the problems of the apartment-dwelling outskirts. Those ideas, however, seemed to have gained more appeal among locked-down Parisians, and Ms. Hidalgo surprised everyone by handily winning a re-election in June.

Montreal Mayor Valérie Plante removes her mask at a Sept. 18 news conference.Ryan Remiorz/The Canadian Press

More realistic might be the transportation and housing ideas of Montreal Mayor Valérie Plante, which some observers have characterized as a “45-minute city” plan – more intended to weave the isolated and car-dependent and lower-income suburbs into city life, and perhaps more suited to a remote-working metropolis. Those ideas got a big boost this year, when a previously hostile provincial government put Montreal transit reforms in its budget for the first time – an opportunity waiting to be seized, if Ms. Plante and her council can determine what shape the city should take after the pandemic.

Despite these examples of cities seizing opportunities, however, most veteran observers agree that the larger changes, in the next months, will be driven not by inventive opportunism but by difficult force of circumstance.

“This pandemic is going to be a particle accelerator – all the things that were dysfunctional in our cities before, manifest themselves now in a much more acute way, and in a lot of cases in a horribly fatal way,” says Mary Rowe, president of the Canadian Urban Institute, a national organization of urban policy makers.

“And I think the more difficult questions are around things that perhaps those governments will be compelled to do. It’s not just about a municipal government wringing its hands and saying, ‘Oh, goody, now we can finally get those bike lanes in.’ I think that’s the low-hanging fruit, so to speak. The bigger challenges are going to be the systemic changes municipal governments need to make – and you’re seeing it expressed so much more viscerally now. If you need to get housing distributed across a metropolitan area because people work in various places now, and you want to make complete neighbourhoods with a range of housing and uses and commercial and retail … I would be interested to see whether the crisis could finally force us to come to a more collective answer.”

But few of those changes will be responses to positive developments or the flowering of pre-existing visions and plans. As the mayors of Lisbon and Victoria found, a crisis that devastates multiple communities and pits them against one another can, with considerable effort, be solved with hard-fought compromises that minimize the damage to various parties. But those felicitous solutions are hard to identify in advance, when you don’t know where the dust will settle.

“With work-from-home, if we’re not careful and pro-active, it can have consequences that weaken cities,” says Brent Toderian, the former chief planner of Vancouver who works as an urban consultant today. “It is not a foregone conclusion that the effects will be positive. It will only be positive if we are pro-active and vigorous in fighting to make them positive.”

Construction workers are seen on a job site in Miami on Sept. 4.Joe Raedle/Getty Images/Getty Images

The phrase “build back better” has become something like a ritual chant in mayor’s offices. But that notion – that the postpandemic reconstruction will allow cities to seize the moment and rebuild their institutions and infrastructure in new, creative ways – is premised on positive developments that are not guaranteed to occur, at least in the short term. If thousands of small business have shuttered – and the city then loses both their business-tax revenues and the life they lend to streets and neighbourhoods – it will make that process of reinvention difficult. Likewise if a large proportion of residents move to the suburbs to telecommute, or if big chunks of office districts try to convert to housing, or if an underfunded recovery provokes an economic depression. It is very difficult to change a city and its institutions for the better during a period of serious decline.

“The people commenting on the implications of the pandemic, they’re doing the same thing – they’re assuming the results will be relatively rosy and they’re assuming it will be quick,” Mr. Toderian says. “The idea that we don’t need to worry about the death of the downtown because we’re going to be replacing urban downtowns with 15-minute communities? Even if that is true, we’re assuming that it will be a success story, but the lag time between the death of the downtown and the physical realization of new communities is probably at best decades.”

Very few city administrations – or business groups, or citizens – are willing to set up contingency plans for those very plausible worst-case scenarios, although they will need to do so at some point soon.

That’s probably why so many of the long-term changes made to cities so far look strikingly similar – a main shopping street turned into a pedestrian thoroughfare, some bike lanes downtown, perhaps some extra subway cars and buses on the ground in order to keep everyone separate.

“The easiest things to think about and talk about and take action on are the obvious things – like sidewalk widths and bike lanes and redesigning streets and outdoor seating,” Mr. Toderian says. “Those are the easy things that we’re tackling, and the easy chances to learn from this pandemic.

“The much harder things are the implications to car dependency, transit ridership, suburban sprawl and successful downtowns, all of which are in play. These are much bigger issues, much more challenging conversations that we need to be having.”

City of dreams

For The Globe and Mail’s series on the future of cities, illustrator and architectural designer Kathleen Fu assembled all the themes of our reporting into one gigantic illustration, which you can see in full below. If you're reading on a mobile device, here is an enlargeable version.

Doug Saunders

Doug Saunders