Cracks are showing in the global economy. Financial markets gyrated wildly this week, as investors took stock of the latest indicators and realized all is not well in the world.

Ever since the financial crisis, the global economy has never operated at full throttle, but there have been several notable bright spots. Now some of those are starting to lose their lustre.

In China, a sudden drop in steel demand is just the latest sign of a broader slowdown that is sending ripple effects around the world. In Germany, a sharp pullback in exports is raising fears that the nation can no longer be counted on as Europe’s economic engine. From Brazil to Russia, emerging markets have failed to live up to expectations that they would provide the next wave of global growth. Here at home, the energy-fuelled Canadian economy is sure to feel the chill of sinking oil prices, but as the loonie tumbles in tandem, exporters are hoping for a better competitive footing in global commerce.

A key wild card is the U.S. economy, which has shown vigour this year. The question is whether that strength can last as other global heavyweights increasingly look tired.

In China, a steel slump as economy cools

By Nathan VanderKlippe in Beijing

For a country whose growth has seemed invincible, it was a number just short of heart-stopping. A few weeks ago, the China Iron and Steel Association reported that domestic demand was no longer rising, as it has in an uninterrupted streak since 2000. It was, instead, falling. In the first eight months of 2014, steel consumption shrank 0.3 per cent.

For investors, miners and even foreign governments whose revenues depend heavily on its demand, China has become the land of eternal economic sunshine. But nearly 40 years after it began to open to the rest of the world, it is increasingly beset by shadows.

Officially, there is little to worry about. Government statistics show growth not far off a 7.5-per-cent gross domestic product increase target for this year. And come December, chances are “they will say, ‘oh guess what? We just made 7.5 through a series of fortunate circumstances’ – like our ability to manipulate data,” said a sarcastic Victor Shih, an associate professor at the University of California at San Diego who has for years raised alarms about the country’s economy.

“At the end of the day, you have to rely on more objective data. And if steel and electricity consumption are both falling, it really suggests the Chinese economy is doing a lot weaker than what the official numbers suggest.”

In August, Chinese power consumption contracted 1.6 per cent; it was up again 2.7 per cent in September, but still far off the roaring double-digit increase of times as recent as 2013. Housing prices across the country are sinking, back-pedalling 2 per cent month to month in some major cities. Both new construction starts and home sales volumes are down roughly 11 per cent this year. Governments have scrambled to get people buying again – reducing transaction fees, cutting rates, even banning publication of negative statistics in some cities. But the price decreases have only accelerated.

Consumer price inflation has fallen to five-year lows – just 1.6 per cent year over year in September. China’s producer price index fell 1.8 per cent last month, its 31st consecutive month of red numbers.

Even official statistics show an unmistakeable slide. If China makes its 7.5-per-cent GDP growth target, it will still mark its worst performance in any year since 1990.

Perhaps nowhere is the shift more startling than in the blast furnaces that have powered China’s rise, pouring out astonishing quantities of steel for new skyscrapers, factories, bridges and high-speed railways. China now consumes half the world’s steel.

But in April and May, Hongwei Iron and Steel, a mid-sized maker of I-beams and other structural products, called a halt to domestic sales. Today, almost everything it makes goes to Southeast Asia and the Middle East, where its product is replacing supplies from Russia and Ukraine that have been blocked by sanctions.

In Hongwei’s lines of business, “domestic steel consumption is reaching its lowest levels in the past 10 years,” said marketing manager Gao Hui. She estimates half the companies like hers in the Tangshan area, long one of the country’s steel strongholds, have halted production.

“This year’s situation has made most factories here lose money,” Ms. Gao said. “Some have even gone bankrupt.”

Some steel is now as cheap, pound for pound, as cabbage. One company desperate for buyers even posted rebar for sale on Alibaba, the online portal more commonly used for sales of boxer briefs, tablet computers and herbal supplements.

It may get worse.

“China’s steel demand peaked this year. Next year it will either stay flat or possibly have negative growth,” said Jim Jia, chief analyst at information portal Mysteel. He estimates current Chinese steel-making capacity at 1.2 billion tonnes a year, but says that this year, output is unlikely to exceed 800 million tonnes. And of that, there is “at least a 20-per-cent oversupply.”

“The situation has changed brutally,” he said.

And as the steel mills go, so go chunks of the economy. China has minted massive wealth from an urban migration unlike any other in human history, which has induced a huge appetite for new buildings, roads and cities. But the average rural age is now approaching 50, and the bottom half of the population has little savings, leaving less incentive or money to buy more property.

As the shadows lengthen, it’s time for a check on “Asiaphoria,” warns new research co-authored by former U.S. Treasury secretary Lawrence Summers. He predicts average Chinese growth of 3.9 per cent over the next two decades, far below its level of the past 20 years.

Yet at the same time, Beijing remains intent on shaping its economy after its own desires, and that means hitting targets. It has overseen a series of mini-stimulus injections – with new money to banks and increased investment in water projects and other infrastructure – that are likely to keep lashing the economy forward.

Things may be slowing, but “Xi Jinping is going to get what he wants. And they’ve been very clear that China is going to grow 7.5 per cent in 2014,” said Greg Anderson, a political risk consultant with Pacific Rim Advisors.

And for now, maybe that’s not so bad.

“Who wouldn’t want 7.5-per-cent growth?”

Germany: Europe’s engine sputters

By Joanna Slater in Berlin

Last week, Horst Linn gathered his 120 employees and delivered some difficult news.

Mr. Linn’s 46-year-old firm, based in Bavaria, is one of the thousands of medium-sized manufacturers that make up the backbone of the German economy. It also happens to get about a third of its revenues from clients in Russia.

Some of its products – industrial furnaces that cast parts for everything from aircraft turbines to cellphones – fell afoul of the sanctions imposed on Russia in the wake of the Ukraine crisis. One such order worth €1-million ($1.4-million) is sitting idly at Mr. Linn’s factory, unable to be shipped. The lost business would mean layoffs of up to 10 per cent of employees and reduced hours, Mr. Linn warned his staff.

“We suffer because of sanctions,” said Mr. Linn, 70. But when he talks to other parts manufacturers in his region, they too say their order pipeline is faltering, albeit less dramatically. “The fact is that the whole world market is slowing down a little bit.”

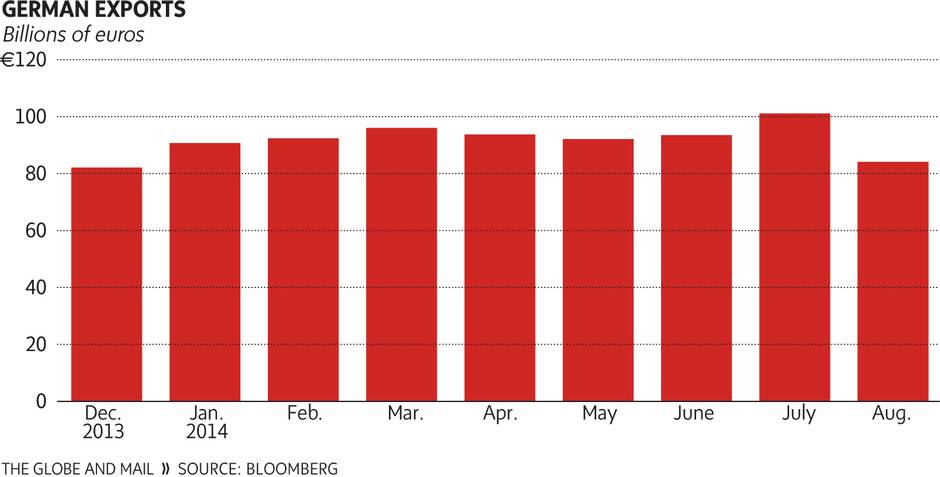

Now that deceleration is causing Germany to stumble. Seemingly overnight, the nation that is the economic engine of Europe has begun to sputter: In August, exports and industrial output posted their largest monthly declines in five years. Earlier this week, a measure of investor confidence fell to its lowest point in two years. The German government also significantly cut its growth forecasts for the economy, from 1.8 per cent to 1.2 per cent this year, and from 2 per cent to 1.3 per cent for 2015.

Some believe Germany is on the brink of a shallow recession, officially measured as two quarters of economic contraction. That’s bad news for the already suffering euro zone, which is struggling to keep output and prices from falling. The situation is also reviving an old and bitter debate about Germany’s fiscal policy. Many experts elsewhere believe the German government should spend much more to stimulate the economy and spur demand at home. But that idea is anathema to Chancellor Angela Merkel, who has pledged to deliver the country’s first balanced budget since the 1960s.

To be sure, Germany’s situation still looks enviable from some perspectives. Unemployment remains low, as do debt levels for households and companies. So how did Germany, the locomotive of Europe, falter? An exporting powerhouse, Germany is grappling with weakness in its closest trading partners and less-robust growth in emerging economies such as China. The geopolitical crisis on its doorstep is also rippling through the economy. While only some firms, like Mr. Linn’s, are directly affected by the sanctions against Russia, the conflict in Ukraine is dampening broader demand and investment.

Some of the downturn is a “psychological reaction to Putin’s war,” said Holger Schmieding, chief economist at Germany’s Berenberg bank. “If you’re in Berlin or Hanover, Russia doesn’t look that far away.”

What’s more, with Russia’s own economy struggling, German firms are seeing opportunities evaporate. “It’s not only uncertainty, it’s also pessimism,” said Ferdinand Fichtner of the German Institute for Economic Research in Berlin. German companies “are quite sure they will not have those chances to export into Russia that they once had.”

Late last month, MAN SE, a large German truck maker, said it was cutting hours for 4,000 workers at plants in Germany and Austria as it grappled with an unforeseen slowdown in demand. A company executive said he expected the European market for trucks to contract by up to 15 per cent this year, while the Russian market shrinks by 25 per cent, according to Reuters.

“The mood in the business community has worsened,” said Volker Trier, chief economist at the German chamber of commerce and industry, DIHK, in Berlin. “It’s not a disaster, but it’s not really confident any more.”

For now, the German government doesn’t believe any major shift is needed in order to address the country’s economic stumble. “We’re not going to help the German economy with some flashes in the pan and more debt,” Sigmar Gabriel, the country’s Economics Minister, said earlier this week.

Ms. Merkel won re-election this year on a campaign platform that included the promise of a balanced budget in 2015, a goal that is popularly dubbed “die schwarze Null” – the black zero. Unless the economic situation deteriorates markedly, experts do not believe Ms. Merkel will jeopardize fulfilling her pledge, no matter how loud the complaints become from other countries in the euro zone that Germany is being excessively frugal.

The German government will not initiate a major domestic spending program “in the hope that repairing German bridges in a rush will somehow help to overcome the reluctance of Italian and French companies to invest in their own countries,” Berenberg’s Mr. Schmieding remarked in a note earlier this week. Germany should, however, stop impeding the European Central Bank from taking further steps to stimulate the region’s moribund economy, he added.

The recent economic setback for Germany is opening the door to some wider introspection, with commentators pointing to problems like aging infrastructure and a shortage of investment by companies. Olaf Gersemann, senior business editor at Die Welt, a major German newspaper, recently published a new book provocatively titled The Germany Bubble: The Last Hurrah of a Great Economic Power. Germany’s economic success over the past decade – one of the first countries to recover from the financial crisis, it became the bulwark of the euro zone – “increasingly went to our heads,” Mr. Gersemann argues. “We tend to overlook our weaknesses and there are many of them.”

Meanwhile, companies such as Linn High Therm GmbH – Mr. Linn’s industrial furnace concern in Bavaria – are trying to muddle through their immediate difficulties. Because the equipment produced by the company is so specialized, “you cannot find new clients around the corner within six months,” Mr. Linn said. “I’m very pessimistic.”

Once poised for growth, emerging markets struggle

By Brian Milner in Toronto

As global growth prospects darken, once-promising emerging powers such as Brazil, Russia and India are in no position to pick up the baton from a faltering China, a stagnant Europe, struggling Japan and still recuperating United States.

These putative heavyweights are not only failing to punch above their weight, they’re having trouble staying on their feet.

“The picture’s not too encouraging,” says Neil Shearing, chief emerging-markets economist with Capital Economics in London. “There’s not much to be optimistic about.”

After three years of stagnation, a deeply uncompetitive Brazil slipped back into recession in the first half of this year for the first time since early 2009.

Battered Russia was on the ropes even before Western sanctions and falling world prices for oil and other commodities compounded the damage from self-inflicted wounds.

Most analysts expect both countries to continue treading water, with little or no growth through next year.

India is regarded as one of the few potential bright spots in the new low-growth world (along with Poland, Mexico and a handful of Southeast Asian nations like the Philippines). That hope stems from the resounding election victory five months ago of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, a reformist who was handed a rare majority government, as well as the determination of hawkish central bank governor Raghuram Rajan to stamp out a chronic inflation problem.

Yet even with a sharp improvement in business and consumer confidence and the benefits of lower commodity prices for a country dependent on resource imports, the weakened Indian economy is expected to barely exceed 5-per-cent real growth this year. That’s an improvement from the anemic level of just under 4.4 per cent in 2013 but a far cry from a high-water mark of 10.3 per cent in 2010.

Many other emerging economies are still expanding, but at such comparatively feeble rates that they too are effectively in a slump.

What really worries Mr. Shearing and other analysts is that the current malaise across a large swath of the emerging world is not merely the result of short-term market reversals but long-standing structural shortcomings that governments have been loath to tackle and which don’t lend themselves to quick or easy fixes.

“It’s about structural reforms. Everything that market investors wanted Europeans to do over the past four years pretty much applies to emerging markets,” says Marko Papic, chief geopolitical strategist with BCA Research in Montreal. “Winners and losers are going to be decided by which countries are willing to incur the pain of structural reform.”

Issues like a lack of competitiveness, rigid labour markets and heavy-handed state interference in the marketplace could be ignored during the halcyon days of the past decade, when emerging-market countries were growing at a clip that was three times faster on average than the U.S., topping out at 8.7 per cent in 2007.

Brazil and other success stories benefited from an “unbelievably favourable combination” of soaring commodity prices and an outsized global risk appetite for emerging-market assets, which lured huge inflows of capital, says Ruchir Sharma, head of emerging markets at Morgan Stanley Investment Management in New York.

Today, the average growth rate in the emerging world has fallen below 4 per cent. Take China out of the equation, and the figure falls to an anemic 2.5 per cent. And no one is touting the Third World’s prospects as an antidote for what ails the developed world.

Falling oil and other commodity prices do help India and such manufacturing powers as South Korea.

“But they all get hurt by lower demand, particularly from China,” says Mr. Sharma, author of Breakout Nations, a 2012 book in which he predicted that capital would pour out of once-hot emerging markets, and those that had used the cash influx to paper over deep-seated structural problems would be hit the hardest.

“They’ve exited the Goldilocks scenario of persistent and repeated releveraging of the American … consumer. That scenario is done. It’s over. And it’s never coming back,” Mr. Papic says.

“I’m comfortable saying that China’s not going to grow [by] double digits and that the American consumer is not going to releverage.”

Weaker oil and loonie ripple through Canada

By Nicolas Van Praet in Montreal

Already struggling to gain traction, the Canadian economy must now contend with falling oil prices, a slumping dollar and a slowdown across much of the world. These new crosscurrents amount to bad news for the key energy sector, and a break for consumers and exporters.

The drop in oil certainly hits producers in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Newfoundland, threatening to dampen the country’s $70-billion in net energy exports over the past 12 months. Governments could see lower corporate income tax receipts and royalties.

But consumers benefit with somewhat cheaper prices at the gas pump and potentially other goods. And a falling dollar helps exporters, such as farmers who sell their products in U.S. dollars. But it also drives up the cost of imports, making it harder for companies to buy new equipment.

“What I’m seeing is a lot of uncertainty, a lot of risk,” said Jayson Myers, president of the Canadian Manufacturers & Exporters. “This is mainly a story about uncertainty in the market and the feeling among investors sort of mirroring the optimism on the part of our members about renewed strength in the U.S. economy.”

Over all, lower oil isn’t good for the Canadian economy, according to Toronto-Dominion Bank economist Randall Bartlett. The benefits of a lower price “tend to be modestly outstripped by the costs to the economy,” he said in a report released Friday. The fast-growing energy sector has long been the bright spot in Canada’s overall sluggish growth in recent years.

But there is more to the story than oil.

Demand has cooled in China, breaking a belief that the country’s voracious consumption would continue unabated. Meanwhile, political instability in the Middle East and Russia and the potential spread of Ebola is piling on investor concern and turning the United States into a perceived safe haven.

The Canadian dollar has weakened in tandem with oil prices, plunging below 89 cents (U.S.). That gives a boost to manufacturers when they repatriate their U.S. export sales to Canada.

For Vancouver-based Polaris Minerals Corp., a maker of sand and gravel concrete aggregates destined entirely for the U.S. market, lower oil prices will mean lower shipping fuel costs and higher profit as U.S. revenue is banked back home.

But lingering investor worry has also hit the company’s stock price, which has tumbled 20 per cent from its level two weeks ago. Amid the fear, investors have shifted to its larger multinational rivals, said Polaris chief executive officer Herb Wilson. That would be a problem if Polaris had to raise money. But it is debt free and doesn’t forecast a need to do so for at least another two years.

“Extreme volatility doesn’t help anyone run their business, whether it’s up or down,” Mr. Wilson said. “But compared to the global recession of 2009-10, I think this is just a minor aberration. The market will correct.”

Hammond Power Solutions Inc. in Guelph, Ont., is loving the low dollar. Its decline makes the transformer maker more cost competitive while improving earnings for products built in Canada and sold in the United States.

Still, the slowdown in many markets, particularly China, looms over the company. CEO Bill Hammond said a significant portion of the manufacturer’s exports, even ones it sells into the United States, is tied to resource extraction in emerging economies. Less mining and drilling means less need for the electric transformers powering industrial equipment. Business in Canada is also down as cash-strapped governments taper spending on public building construction.

“We’re struggling this year,” Mr. Hammond said. “Any reduction in the Canadian dollar will help us today and going forward. We know we can’t hide behind a 63-cent dollar like we did eight or nine years ago. But at the same time, there has to be a recognition that the Canadian dollar can’t be at par with the U.S. because our costs are too high here.”

Canadian corporate leaders are likely to remain on edge as a result of the market volatility seen in recent weeks.

“The impact is slightly negative for Canada as a whole because of course [lower oil prices] discourages investment in the West,” Quebec Finance Minister Carlos Leitao said in an interview. “And even in Ontario and Quebec, if businesses interpret the oil price decline as a sign that global demand is weakening, then they might also slow down their investment plans.”

Going back over the past 20 to 25 years, there have probably been more than 10 times where oil prices have fallen as quickly as this month, said Bank of Montreal chief economist Douglas Porter.

“It’s too soon” for most Canadian companies to contemplate a change business model because of recent events, Mr. Porter said. “They have to believe there is a fundamental change. And I don’t think that’s obvious just yet.”