Construction on Enbridge’s Line 3 Replacement Program progresses in 2017.Enbridge

In a muddy trench just south of Duluth, Minn., an Enbridge Inc. work crew is hunting for microscopic cracks and dents on a stretch of exposed pipeline that is older than Alberta’s oil sands industry.

It’s an expensive and time-consuming job, and a key reason Enbridge aims to spend $9-billion to replace the severely corroded 1960s-era pipeline, known as Line 3.

“We don’t want to come out here in the swamps and disturb everything,” says Heath Larson, a construction co-ordinator with the company, leaning in over the thrum of a diesel engine on a recent morning. “We’d rather just have a new line.”

But whether a new Line 3 will actually get built is still unclear – and one of a growing number of questions facing North America’s top pipeline company.

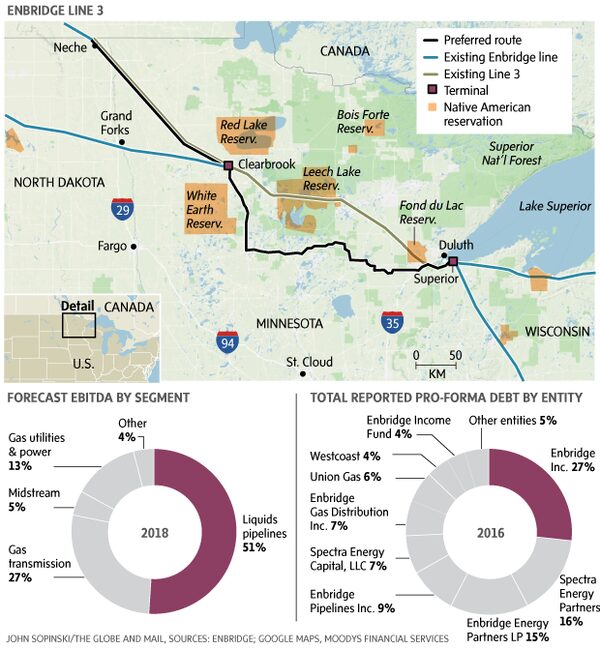

Minnesota’s commerce department last September concluded that replacement of the Alberta-to-Wisconsin pipeline isn’t needed, saying local refineries don’t need the extra oil it would bring. And the state’s powerful Indigenous tribes remain staunchly against it, fearing impacts on water and traditional rights.

Enbridge, for its part, says an upgraded Line 3 would improve safety and help relieve congestion on a key shipping route for Canadian crude, a problem that is causing big price discounts for the country’s oil producers.

At stake is the most expensive pipeline the company has ever contemplated, and a central piece of chief executive officer Al Monaco’s ambitious $22-billion growth plan.

The uncertainty around Enbridge’s plan to replace a leaky pipeline with a brand new one is emblematic of larger disruptions shaking the energy-infrastructure giant. They include concerns about its complex operations and finances that have multiplied following its splashy $37-billion acquisition, in 2016, of U.S. rival Spectra Energy Corp.

That apprehension is an abrupt change for a company that for years enjoyed solid, predictable growth from a host of new projects. Enbridge reaped big benefits as surging oil prices triggered an investment boom in Alberta’s oil sands during the last decade. Oil-company shippers flocked to its mainline pipeline as rival export projects were tripped up by regulatory hurdles and environmental opposition. That propelled Enbridge shares and delivered steady growth in earnings and dividends, cementing the company’s status as a blue-chip holding for large institutions and legions of dividend-hungry small investors.

Yet, that trajectory suddenly looks choppy. Today, the company is saddled with about $61-billion in debt, a burden that has stoked concern as interest rates edge up. Enbridge’s dividend yield has jumped to nearly 7 per cent, indicating some unease among investors. Meanwhile, the oil sands boom has fizzled and longstanding tenets of the business model are being rewritten.

Enbridge’s stock price has tumbled roughly 30 per cent since the company announced the Spectra deal and this month touched a six-year low. While some of the retreat has come from a recent broad shift out of many dividend-paying stocks, Enbridge shares have fallen about 11 per cent over five years.

Under pressure to shore up finances, Enbridge late last year issued $1.5-billion in common equity, throttled back dividend growth and flagged $10-billion in assets for sale, the culmination of an extensive strategic review.

Assets on the block include some natural gas processing infrastructure as well as its onshore renewable energy business, reflecting a retrenchment toward regulated assets and those supported by long-term contracts that promise steadier returns.

With its acquisition of Spectra, Enbridge hopes to capture a bigger slice of the North American shale gas revolution to diversify risks. This comes as its traditional oil-shipping business faces stiff headwinds.

The Spectra deal coincided with a $30-billion selloff by Royal Dutch Shell PLC, ConocoPhillips Co. and others from the oil sands. The retreat has undermined bullish production forecasts for the region and sparked fears that pipelines proposed by TransCanada Corp. and Kinder Morgan Inc. could, if built, eventually siphon some volume away from Enbridge’s key mainline shipping network.

It all leaves CEO Mr. Monaco facing the prospect of slower growth, at a time when the company tries to allay concerns over its ability to fund billions in expansion projects, including Line 3.

“This was, at one point, a $5-billion market cap company. It grew to $40-billion. And it has been a nice, steady rise. But remember, a lot of that was underpinned by oil going from US$30 to US$100, and all of these crazy, big capital projects in front of them,” says Manash Goswami, a portfolio manager in Toronto at First Asset Management, which owns the shares.

But Enbridge, now a $68-billion company, has hit a crossroads. “It’s a different job moving a vast, market-cap company like this forward,” Mr. Goswami says.

Al Monaco, president and CEO of Enbridge, prepares to address the company's annual meeting in Calgary, Thursday, May 12, 2016.Jeff McIntosh/THE CANADIAN PRESS

Not according to plan

The oil world was on the cusp of tremendous change when Mr. Monaco sat for an interview on CNBC’s Mad Money in October, 2012.

It marked his first week at the company’s helm, a fact that didn’t escape his gushing host. “You’re kind of the man of the hour, frankly,” Jim Cramer began. He asked about the drilling frenzy that was gaining momentum in the United States.

Could the boom really create four million jobs, as claimed by then Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney?

“Absolutely, and the reason for that is because we’re going to see unprecedented growth in crude oil supply in North America, and particularly in the United States,” Mr. Monaco replied.

Enbridge had added 2,500 positions that year and was “right in the middle of that transformation,” he said. “So yes, the jobs will come.”

The transformation has not gone entirely to plan.

The boom created a glut that sent oil prices tumbling below US$30 a barrel in early 2016. Across North America, oil companies slashed jobs, idled rigs and scrapped dividends to preserve cash as the worst slump in a generation intensified.

Major pipeline companies were less exposed as the tide went out, but the downturn nevertheless stoked fears of falling tariffs and overcapacity as oil-shipper customers slashed spending or went out of business.

U.S. crude prices have since rebounded to around US$65, but Enbridge now faces a level of skepticism that its chief executive acknowledges is unprecedented. “I don’t think we’ve really gone through a time like this, at least in the last five years,” Mr. Monaco said during a lengthy interview at the company’s Calgary headquarters.

“We were always looking at a decreasing interest-rate environment, new capital projects were always good and, I think, in this environment, investors are more sensitive to those issues, for sure.”

Throughout the downturn, Enbridge stressed that only a fraction of its business was at direct risk from slumping oil prices and that the majority of volumes it transports are tied to companies with investment-grade credit ratings, including big refineries in the United States.

In an Aug. 21, 2017 photo, a pipe fitter lays the finishing touches to a segment of pipeline.Richard Tsong-Taatarii/The Associated Press

But it was also forced to shore up finances within its web of subsidiaries. Among other moves, that prompted a US$1.3-billion acquisition, last year, of Enbridge Energy’s interests in the money-losing Midcoast natural gas business.

Buying Spectra has reduced by roughly one-quarter Enbridge’s reliance on shipping crude while adding heft in fast-growing shale gas regions in British Columbia and the Northeastern United States.

The move into gas “opens up a huge number of opportunities” for the company, Mr. Monaco says today. Enbridge’s footprint now extends through New York and Boston in the U.S. Northeast, and as far as Florida in the Southeast.

“But the big kahuna is this volume coming down now from the Marcellus into the Gulf Coast petrochemical complex,” he says, tracing on a map the company’s Texas East Transmission system.

The jumbo network taps the prolific Pennsylvania gas formation and gives Enbridge exposure to growing U.S. energy exports, a trend he says is likely to pull a growing share of its capital spending south of the border in coming years.

In Ontario, Enbridge is projecting cost savings of up to $750-million from a proposed merger of Spectra’s Union Gas distribution network with its own franchise.

But the proposal has drawn criticism from labour groups concerned about job losses and industrial consumers of natural gas that argue it benefits shareholders at the expense of ratepayers.

The natural-gas utilities are one of three “crown jewel” businesses Mr. Monaco says are Enbridge’s future, in addition to highly regulated oil transportation and natural gas transmission and storage.

The utility-like profile of the business could mean slower growth, says Darryl McCoubrey, vice-president of utilities and industrials at Veritas Investment Research in Toronto. He sees risks to Enbridge’s bread-and-butter oil-shipping business if more pipelines start competing for fewer barrels following the industry-wide downturn.

The big export lines are chock full today, reflecting oil sands investments made before prices crashed. But in a sign of heightened competition, the company last year called Alberta government support for TransCanada’s Keystone XL an unnecessary subsidy.

“It’s a bit of sour grapes, right?” Mr. McCoubrey says.

“The days of them growing via asset investments that are providing return on equity of 15 to 20 per cent, which is kind of what a lot of these crude oil assets have been doing for them, that market is likely gone now,” he added.

Mr. Monaco says Enbridge’s mainline remains highly competitive with proposed alternatives. And, he notes, the company is still building new projects, including $12-billion of new pipelines placed into service last year.

Earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization are forecast to reach about $12.5-billion this year. With Spectra, the company now has a bigger asset base from which to expand – a major advantage given widespread opposition to new infrastructure.

“If anything, the value of assets in the ground has increased,” he says. “We’re going through some market turbulence right now, but those assets aren’t going away.”

Construction workers operate heavy machinery along the Line 3 pipeline.Enbridge

Line 3 launch remains an unknown

Still, the company has been buffeted by questions over its complex corporate structure. The biggest relate to funding concerns for billions of dollars in planned infrastructure projects.

Enbridge has said it expects to fund growth through a combination of internally generated cash flow, hybrid securities and asset sales, including $3-billion targeted for this year. However, a long-held cost-of-capital advantage enjoyed by its subsidiaries is under pressure.

Its Canadian oil pipelines are held in the Enbridge Income Fund, a subsidiary that has been knocked by Moody’s Investors Service for its tangled capital and organizational makeup.

Enbridge Inc. transferred those assets to the Canadian unit in a 2014 transaction known as a drop-down, a move it said would help fund growth cheaply and improve returns at the parent-company level.

That strategy is less effective today, in part because the unit, Enbridge Income Fund, has traded at a lower valuation than the parent, says Laura Lau, senior portfolio manager at Brompton Funds in Toronto. There is also finite demand for new equity among retail investors who hold the fund, she says.

“You can’t dictate to the market what the valuation should be. So that’s part of the problem,” she says, reflecting a wider criticism of the company. “There’s been too much financial engineering, and now it’s a little more complex because they also bought Spectra.”

This month’s decision by the U.S. Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to remove certain tax allowances enjoyed by master-limited partnerships (MLPs) has added to the strain. Analysts say it reduces the appeal of tapping Enbridge’s U.S. units to fund growth.

Mr. Monaco says the change will have minimal impacts on Enbridge, and that the company has taken steps to simplify operations following the Spectra deal. They include a major restructuring at its U.S. subsidiary, Enbridge Energy Partners LP, last year and more recent moves to streamline Spectra Energy Partners LP, another affiliate.

There is more to do, he says, although the company has said it has no immediate plans for a broader consolidation that would put its various units under one roof.

“I think the MLP space has been under pressure for a while, for a bunch of reasons. And I think that this is certainly another challenge that is going to make everybody look at the structures in ways that may help to offset this kind of impact,” he says.

Enbridge has also taken heat for dialing back growth targets with little fanfare.

The company initially said the Spectra deal would support annual per-share cash flow growth in the range of 12 per cent to 14 per cent through 2019. That equated to $6.32 a share in 2020, according to JPMorgan Chase & Co. analyst Jeremy Tonet.

In November, the outlook was revised to 10 per cent through 2020, putting forecast available cash flow from operations at $5 a share. It was a sharp reduction some feel dented the company’s credibility.

“An inability to deliver on that, no doubt, has had a negative impact,” says Rob Thummel at Tortoise Capital Advisors, which owns the shares. “They’re kind of hitting the reset button here a little bit.”

Mr. Monaco says the change reflected lower volumes in its natural gas-gathering and processing business in the United States, as well as the company’s decision to speed up debt reduction.

The acquisition added roughly US$14.5-billion in Spectra debt to Enbridge’s balance sheet. The company has said it aims to cut total debt to five times earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization by the end of the year, as new pipeline projects start up. (Moody’s in December pegged debt-to-EBITDA at 6.4 times on an annualized basis.)

The ratings agency late last year downgraded Enbridge’s debt to one notch above junk status, citing “execution risks” in the company’s financial blueprint, which it said would be slow to deliver results.

Although the company says it’s not critical to meeting year-end leverage targets, one of the biggest unknowns is whether the already-delayed Line 3 expansion starts up by 2020 as planned.

“Once these projects are in service, they generate stable cash flows,” Moody’s vice-president Gavin MacFarlane says. “In that sense, they broadly look like the rest of the company: stable, long-term cash-flow generation. The big challenge, though, is getting them done.”

Tribal and environmental groups opposed to the proposed Enbridge Line 3 project rally Thursday, Sept. 28, 2017 at the State Capitol in St. Paul, Minn.Jim Mone/The Associated Press

“We are preparing to camp”

In Minnesota, Line 3 has touched off a debate about oil in a region where the company’s pipelines have operated for more than half a century.

Enbridge refers to the multibillion-dollar plan as a maintenance project, yet it would boost the flow of Canadian oil through the lake-dotted state by nearly 370,000 barrels a day.

A big concern is Enbridge’s plan to deactivate and leave in the ground the old line once the new one starts up, says Craig Sterle, 63, a retired forester and member of a local conservation group. It’s akin to “a renter leaving his junked-out car in the driveway,” he says. “If they put it in, they should be able to take it out.”

Enbridge says removing the whole line is not practical, in part because of congestion on the existing corridor. The plan instead is to disconnect, clean and seal the line.

The old pipeline runs nearly 1,800 kilometres south and east from the Alberta oil nexus of Hardisty through Saskatchewan and Manitoba before clipping North Dakota and cutting across northern Minnesota to Superior, Wis.

Line 3 is one of seven steel pipes that comprise Enbridge’s mainline to Clearbrook, Minn. From there, six lines continue to Superior, home to vast storage tanks emblazoned with Enbridge’s corporate logo and steady tanker-truck traffic into a small Husky Energy Inc. refinery, also in Superior.

Total mainline capacity on the system is 2.85 million barrels of oil a day, but Line 3 is showing its age.

Built in 1963, the conduit has suffered numerous leaks over the years – a 1991 spill ranks as the biggest in Minnesota’s history – and today is limited to operating at a little more than half its 760,000 barrel-a-day capacity.

Enbridge told state regulators that no other pipeline in its mainline system is so corroded, and the company forecasts maintenance costs could run into the billions of dollars as the line deteriorates in coming decades.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau in late 2016 approved a replacement project in Canada, and construction is already under way north of the border. A segment of the new pipe is finished in Wisconsin.

But a decision on the project from Minnesota’s Public Utilities Commission isn’t expected until June. That has transformed the state into an unlikely front in the pipeline wars.

Indigenous tribes argue Line 3 poses a threat to treaty rights to harvest manomin, or wild rice. Some have accused Enbridge of misleading people by portraying Line 3 as a rebuild of an existing line, when it will actually carve a new path through the state, south of the original corridor.

Many trace animosity in part to Enbridge’s decision, in September, 2016, to buy a minority stake of the contentious Dakota Access Pipeline, which was marred by violent clashes during construction.

“A lot of people, our whole lives are up here,” says Winona Laduke, an Ojibwa from the White Earth reservation and veteran of the Dakota Access fight.

“It’s not like things used to be; we used to fish, we used to rice,” she says. “We do right now. And they’re putting the pipeline proposal across some of our best territory. And we’re done. We are preparing to camp.”

Enbridge says it has responded to concerns and in some cases shifted the route to avoid sensitive areas, and Minnesota regulators this month deemed a state environmental impact assessment adequate.

The decision was a victory for Enbridge, although tribes pledged to appeal on grounds the study didn’t adequately assess impacts on waters and other wilderness areas.

Despite threats of blockades and litigation, Mr. Monaco insists the new Line 3 will start up by 2020. He argues the project is no different than upgrading a clapped out bridge or railway – a critical piece of infrastructure in need of repair. “This is a project that needs to be done,” he says.

Enbridge is also obligated to replace Line 3 by terms of a settlement it reached with the U.S. government following a 2010 rupture on a pipeline of similar vintage in Marshall, Mich.

The company says restoring capacity on Line 3 to historical levels would ease, but not clear, bottlenecks that have contributed to hefty price discounts on oil sands crude and wreaked havoc with oil rich Alberta’s finances.

Big local refineries owned by Andeavor and Koch Industries, in St. Paul and Pine Bend, Minn., respectively, would benefit as a result, Enbridge says. Numerous municipal counties and a majority of landowners along the route through the state also support the plan, the company says.

But these days, that’s no guarantee. At the dig site near Duluth, three men in fluorescent vests chip away at the earth-encrusted pipe with shovels. The banter is uneven. Someone says approval looks iffy. Another says Line 3 will get built, no question.

It makes sense, Mr. Larson agrees. A new line would be safer, and reduce maintenance costs, the construction co-ordinator says. “If the new line was in, we wouldn’t even be here.”