Madeleine 'Maddie' White as a newborn, beside Mémère’s muffins, on their way to the Second Cup cafes in Sudbury, Ont.Handout

Mémère is a term of endearment for grandmother in French Canadian culture. But it’s also so much more. Mémères are often the glue of family, the purveyors of culture and the guardian of recipes.

My mémère was Velma Bois. Through the fog of time, I can picture my mother’s mother perfectly, standing by her oven, apron on. The warm air smells of cinnamon and the perfectly browned muffins speckled with tiny orange bits are lined up on the table. Each one is so big, I’m pretty sure they are the size of my five-year-old head.

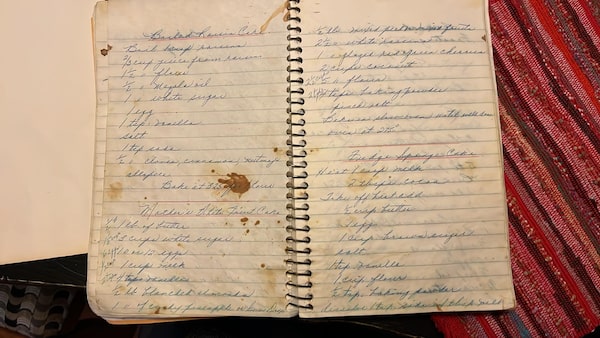

Those carrot muffins, along with various loaf cakes, squares and cookies, were Mémère’s calling card. For about 20 years, she was the anonymous woman baking for all of the Second Cup cafés in Sudbury, Ont. Her spiral-bound recipe book, with perfect cursive script and batter stains, is not only filled with ingredients and instructions (some more completed than others), but also keeps alive stories that serve as a window into the lives of my Franco-Ontarian ancestors.

As the years pass since her death in 2004, her handwritten notes have been fading like my memories of her. In hopes of preserving her memory, my family is turning her recipes into a digitized cookbook.

“This cookbook solidifies her memory,” said my mom, Carole White. “And honours how much work it is to have done all of this baking.”

The original copy of Velma Bois's cookbook. Maddie’s mother, Carole White; sister, Nicole Gray, and aunt, Pierrette Prince, are working on the digitized cookbook.Handout

This project has also been a history lesson about the resilient cultural legacy of our food. Before starting work on the cookbook, all I knew about Franco-Ontarian food was the holy trinity of ingredients that were ever-present in my upbringing: butter, brown sugar and cream. (The butter tart might as well be our patron saint.) But this style of food – while rich in taste – was borne out of practicality and poverty. As Serge Dupuis, historian and research chair on French language and culture in North America at the Laval University in Quebec City, explained, most Franco-Ontarian families began as men left Quebec to look for work.

Often, Franco-Ontarian ancestors “were the kind of people who had nothing to lose in emigrating. In fact, they had everything to gain,” said Dupuis.

My great-grandfather, Napoleon Bois, was one of these men. He arrived in Northern Ontario around the start of the 1900s, where he began a family with my great-grandmother, Eva Paradis, and had 11 children. My Mémère Velma was the youngest.

That Catholic predilection for having many children, coupled with his modest income as a general labourer, meant the family had to be creative with food.

Take, for example, the charming dessert called pets de sœur, which translates literally to nun’s farts. (No one ever promised Franco-Ontarian food would be classy.) This pastry emerged from the working-class ethic that no food scrap can be left unused. So whenever a pie was being made – be it a golden, gooey tarte au sucre (a brown sugar pie) or a savoury, spicy tourtière (meat pie) – the left-over dough would be coated in butter, sugar and cinnamon and curled up into a cookie-like pastry.

“Innovative food comes out of necessity,” said Émilie Bourgeault-Tassé, a professor and consultant based in Sudbury, who, along with her sister, journalist Isabelle Bourgeault-Tassé, is an unofficial custodian of Franco-Ontarian culture. Their mémère was also a pivotal person in their family tree.

“My grandmother has always been my cris de cœur … my battle cry for culture,” Isabelle said.

Velma Bois, left, with her sister, Germaine.Handout

Beyond practicality, another common theme in our shared culinary history is competition, the Bourgeault-Tassé sisters said. This would explain why my family cookbook has six different fudge recipes, the best one being Great Aunt Georgette’s, which were little soft bricks of edible gold that make my mouth water, packed full of brown sugar, sweetened condensed milk and butter (with a stern note that this is not to be substituted for margarine). Award-worthy, no doubt. But legend has it that Georgette, who is remembered as a the beloved “trickster” of the family, stole the recipe from the candy factory she was working in at the time in order to best her sisters.

There’s so much more than ingredients that goes into the food we eat. What we cook and how we cook also tells us about our values, according to Benjamin Hill, an associate professor at Western University who studies the philosophy of food.

“These values can be given to us, and we adopt them in a way that might be somewhat uncritical.”

He uses the example of “salt of the earth” and “meat-and-potato people” – both evocative of diets, class and notions of a strong work ethic.

When I look at the more than 250 recipes in my family’s cookbook, the value that stands out is community. Beyond her sisters, my mémère had recipes that came from her extended family and her friends. This was a collective of women who worked together to better feed their families.

Above all, my mémère loved baking for other people and what she baked reflected her sweet personality. She loved pretty things and pastel colours. And so one of her favourite desserts was a marshmallow square: handmade squishy marshmallow layered on top of crispy shortbread cookie and gently dyed a soft pink or pale green.

“I think feeding people was her way of showing her love,” said my aunt Pierrette. “She knew what you liked. And that’s what she would make when you visited.”

When it came to celebrations, be it holidays, birthdays or bridal showers, my mémère would cover the table in platters of finger foods: tea cakes, cookies, squares and slices of different loaves. There might be a plate of veggies thrown in too. And more often than not, a show-stopping cake at the centre. All of this effort is partly why so many people today are still asking for Mémère Velma’s recipes.

Ultimately, Mémère created happy memories for people through her food. And with this cookbook, we’re trying to do the same for a new generation. Baking with my three-year-old niece, Lucy Velma, named after her great-grandmother, has taken on new meaning since we started this project. Now, a molasses cookie isn’t just a cookie, but a connection to more than a hundred years of her Franco-Ontarian family.

Spiced Raisin Cake.Nicole Gray/The Globe and Mail

Recipe for Spiced Raisin Cake

Originally named the “boiled raisin cake,” we’ve rebranded this recipe to pay tribute to its standout quality: its spiciness. This is deliciously moist and like a sticky toffee pudding when paired with Velma’s caramel sauce. It’s also an old recipe that dates back to the Depression, and in today’s times of high food prices, it’s a cheap way to make something special.

Ingredients

1 cup raisins

⅔ cup juice from the raisins (see method)

½ cup oil

1 cup white sugar

1 egg

1 tsp vanilla

½ tsp salt

1 ½ cup all-purpose flour, sifted

1 tsp baking soda

½ tsp each cloves, cinnamon, nutmeg and allspice

Equipment

This recipe can either be baked in a standard loaf pan, or six mini bundt cake moulds.

Method

- Butter and line the loaf pan. Or butter and lightly flour the mini bundt molds.

- Rinse a cup of raisins. On the stove, bring the rinsed raisins and 1 cup of water to a boil. Boil for about one minute. Strain the raisins but reserve ⅔ cup of juice from the raisins. Set aside.

- In a bowl add the oil and sugar and beat with an electric mixer or whisk until smooth. Add the egg, vanilla, salt. Beat until combined.

- Whisk together the flour, baking soda, cloves, cinnamon, nutmeg and allspice.

- Alternate adding the reserved raisin juice with the dry ingredients to the wet ingredients (sugar and oil mixture). Whisk to break up any chunks of flour.

- Gently fold in the raisins using a spatula.

- Bake the loaf at 325 F for one hour. Or, if using the mini bundt moulds, bake at 325 F for 30 minutes.

Tip: Be sure not to undercook. Use a long toothpick or a wooden skewer to test. If the toothpick/skewer comes out relatively clean (a few little crumbs are fine), the cake is done.

Caramel sauce being added to the spiced raisin cake.Nicole Gray/The Globe and Mail

Caramel Sauce

This makes about seven cups of caramel sauce, which can be jarred, and shared, if you’re feeling generous.

Ingredients

4 cups brown sugar

1 ½ cups corn syrup

1 cup butter, cubed

1 cup cold water

1 can sweetened condensed milk

Method

- Heat sugar, corn syrup and butter on medium heat to a simmering boil. There should be lots of slow, big bubbles as the moisture evaporates. This step takes about 20 to 30 minutes. Stir constantly using a heat-proof spatula so the bottom doesn’t burn.

- If you have a candy thermometer, you are aiming for a “soft ball” temperature, about 230 F to 240 F. If not, look for the sauce to be thick but still stirrable.

- Remove from heat and slowly add 1 cup of cold water, mixing well. Be careful not to pour too fast.

- Add the condensed milk and mix using a wooden spoon.

- Pour into glass jars. Keep refrigerated.

Do you have what it takes to complete The Globe’s giant holiay crossword?

Download the puzzle here or look for it in the paper Saturday, Dec. 23. Share your progress with us on social media using the hashtag #GlobeCrossword.

Madeleine White

Madeleine White