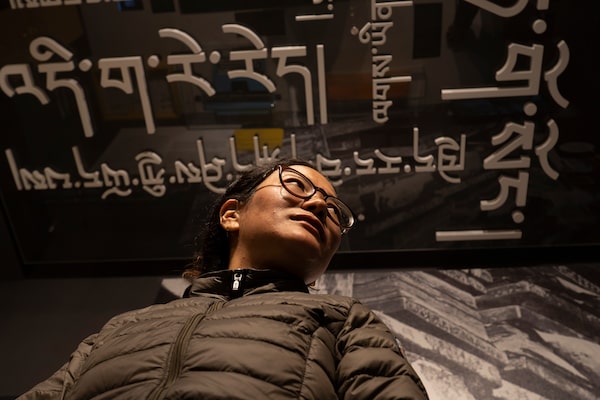

Penthok, a Tibetan journalist and researcher, used to find it 'relatively easy' to get information out of the Chinese-controlled territory, but no longer.Ruhani Kaur/The Globe and Mail

On Feb. 25, 2022, Tibetan pop star Tsewang Norbu walked to a monument in central Lhasa near the Potala Palace, former home of the Dalai Lama. Amid a crowd of tourists and commuters, he doused his body in fuel and set himself on fire.

Mr. Norbu, who had appeared on China’s version of The Voice, reportedly died in a hospital in the Tibetan capital a few days later, amid heavy security and an information blackout by Chinese media. Much about the 25-year-old’s self-immolation and death remains shrouded in mystery almost a year later.

“He was so well known all over Tibet and even China, and he self-immolated in front of at least a hundred people, all of whom had phones, but none of that information got out for weeks,” said Lobsang Gyatso, a researcher at the Tibet Action Institute (TAI), an NGO based in Dharamshala, India. “People knew somebody had self-immolated but they didn’t know it was him.”

China's flag flies at a plaza near the Potala Palace in Lhasa. Pop star Tsewang Norbu immolated himself nearby last year.Mark Schiefelbein/The Associated Press

Mr. Norbu is one of an estimated 160 Tibetans who have killed themselves in this manner since 2009, in protest against Beijing’s policies toward Chinese-controlled but nominally autonomous Tibet, which have grown increasingly draconian and assimilatory in recent decades. Self-immolations peaked in 2012 and 2013, in an initial wave that resulted in worldwide attention and a steady stream of gory, hard-to-look at images and videos.

But while such incidents have become rarer, they have not stopped entirely, and other protests and unrest also take place sporadically in Tibet, both over local issues and national frustrations, such as COVID-19 lockdowns. What has changed is the amount of information making it out, which researchers and activists say has slowed to a trickle in recent years, turning Tibet into more of a black hole than ever before and effectively expunging it from global coverage, despite attention paid to China being at an all-time high.

In 2018, a guard tower and fence loom over a facility in Artux, Xinjiang, that human-rights groups allege is a re-education camp for Uyghurs.Ng Han Guan/The Associated Press

Even Xinjiang, the Chinese territory north of the Tibetan plateau where Beijing has been accused of widespread human-rights abuses against Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities, is relatively transparent by comparison.

The Globe and Mail was able to visit what Beijing terms “vocational education and training centres” in Xinjiang in 2018, as did other journalists in the years that followed, shining a light on what would become a global scandal. But foreign media are barred from the Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR), except on tightly controlled government tours, and even Tibetan areas in other provinces are closely monitored, with an Associated Press reporter detained and expelled from western Sichuan around the time of Mr. Norbu’s death.

“Before 2014, getting information out of Tibet was relatively easy,” said Penthok, a Tibetan journalist and researcher based in Dharamshala, the spiritual and political heart of the Tibetan exile community since the Dalai Lama fled there in 1959. “But after the first wave of self-immolations, there was a clampdown, and the level of persecution in non-TAR areas reached the same level as in the TAR.”

Tibetans who once shared information with contacts outside the country have been silenced, their phone and internet communications surveilled and the fear of informers ever present. Penthok, who like many Tibetans goes by a single name, said even when sources do reach out, she has to weigh the potential costs of using their information, because often “it would be easy for the Chinese to pinpoint who was talking.”

“I have a lot of anxiety about what could happen,” she said. “It’s not just for the person involved, but also their family, their children. It makes it very difficult to build sources.”

Penthok says she worries for the safety of those who try to get information about Tibet past China’s barrier of silence.Ruhani Kaur/The Globe and Mail

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/B5QRMHXV5BFYPCMJHP27SRYSQQ.jpg)

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/BGKMUDS2OJAQXL7MH7VVFOZZQY.jpg)

Dawa Tsering, director of the Tibet Policy Institute, the government-in-exile’s official think tank, said that he too often receives information that he cannot publish, though it is still useful for intelligence purposes. And he worries the flow could be reduced even more as the task of publicizing what happens in Tibet moves from first-generation exiles like him to those born outside the country.

“Second- or third-generation Tibetans cannot build the same level of trust,” he said. “There is also not the same kind of organic connection; there’s a context gap.”

In the past, new refugees arriving in Dharamshala would provide a steady supply of information and bring with them links to potential sources back home. But the number of Tibetans making it out of the country has dwindled in recent years, and almost completely dropped off during the COVID-19 pandemic, which also curtailed another key source – the businesspeople and traders who work the Nepal-Tibet border.

Penthok said she increasingly relies on open-source intelligence, scouring social media and internet forums for news that may have escaped the attention of the censors.

When Mr. Norbu self-immolated, she said, one way his death was publicized was through people changing their profile pictures on microblogging site Weibo and other social-media platforms to black-and-white photos of the late singer, or posting oblique condolences that did not mention his name or how he died.

“But even some of these spaces are now closing up,” Penthok added.

Dorjee Phuntsok and Tenzin Thayai of the Tibet Action Institute speak about the technological challenges of bypassing China's information barriers.Ruhani Kaur/The Globe and Mail

The Great Firewall of China, the country’s vast online surveillance and censorship apparatus, has grown ever more opaque in the past decade. In the past, tech-savvy individuals or those with foreign connections could download encrypted messaging apps and virtual private networks (VPNs) to bust through the controls, but these are increasingly difficult to come by and new laws mean those found with such software on their devices could be detained or face potential prosecution.

Tenzin Thayai, digital security program manager at TAI, said it can be difficult for anyone in China to communicate safely online, and people self-censor when they use apps such as Tencent’s WeChat, which are known to be tightly surveilled and censored.

“People still communicate with their family in India, but they don’t talk politics,” Mr. Thayai said.

The resulting reduction in the flow of information both increases how cut off many Tibetans outside the country feel from their family and home, and affects how the international media write about Tibet – or, as is more often the case, don’t.

“Coverage has to be based on verifiable information,” Penthok said. “Even if the media want to report on these things, often they can’t.”

James Griffiths

James Griffiths