In the late 1970s, this was the stamp of The Globe and Mail's China bureau. Former bureau chief John Fraser said he loved filling out forms with it: 'This is a marvelous object carved out of marble, with a fierce beast on top and The Globe's identity chiseled out in Chinese characters on the stamping surface.'The Globe and Mail

More below • More from this series • The Globe in China: A visual history

On the first of July this year, China’s Communist Party will drape itself in the regalia of success. In 1921, according to the official accounts, the Party was formed in the tumult of the post-imperial era. A century later, it commands the world’s second-largest economy, a military that is rapidly growing in strength and a population increasingly certain the future belongs to them.

If China’s current course holds, economists say, it will eclipse the United States as the world’s pre-eminent economic power sometime in the next decade or two. Whether China’s leadership can indeed hold that course is among the defining questions of our time.

I moved to Beijing in 2013 to become The Globe and Mail’s correspondent in Asia. My arrival roughly coincided with Xi Jinping’s ascension to power, and my time in China has been spent documenting the changes he has wrought in a rule defined by intense personal and national ambition.

Later this month, my family and I expect to leave China. Much has changed since we made the country our home. The suffocating smog that once led transit buses to get lost on their own routes has noticeably lightened. A cash system that once kept wallets full to bursting has virtually disappeared, replaced by the frenetic innovation of a mobile payment economy. Hundreds of human-rights lawyers have been arrested or locked up and millions of Uyghurs indoctrinated, incarcerated and sent to work in factories. Mosques have been torn down and crosses removed. China’s diplomacy has grown a sharp edge while its industrial policy has sought to slice into areas where western countries dominate. The shadow of rapid aging looms, but the spectre of extreme poverty has been dispatched. The bullet trains are faster – the futuristic “Rejuvenation” model now, in a telling shift, overtaking the “Harmony” model – and the drive for technological autonomy, if not supremacy, has grown even more vigorous.

One thing has not changed: Mr. Xi remains the force behind China’s bid to reshape the contours of the world we live in. For him, a leader who has swept away term limits, what’s still to come promises to be as momentous as the change that has already swept the country.

China’s Communist Party stands at the threshold of a new century.

But can it continue to march forward? Or will it falter?

That question leads naturally to many others. The reports in this section are my attempt to wrestle with some of the more weighty – and whimsical – among them. It’s my hope that, even when the answers I have found are not definitive, the insights they spark can illuminate the complexities of China today, and the potential stumbling blocks in its path.

More from this series

Watch: Nathan VanderKlippe outlines some key areas to watch around China’s political and economic ambitions as it also represses ethnic minorities and holds two Canadians captive.

The Globe and Mail

China lags on innovation. Can it catch up?

Can China find enough water to flourish?

Can China become a soccer superpower?

Can robots offset China’s population decrease?

Can China use artificial intelligence to perfect central planning?

Can China make its people happy?

China prizes education, so why are some children still left behind?

Why do so many Chinese international students in Canada end up back home?

Can China’s archeologists redefine what it means to be Chinese?

The Globe in China: A visual history

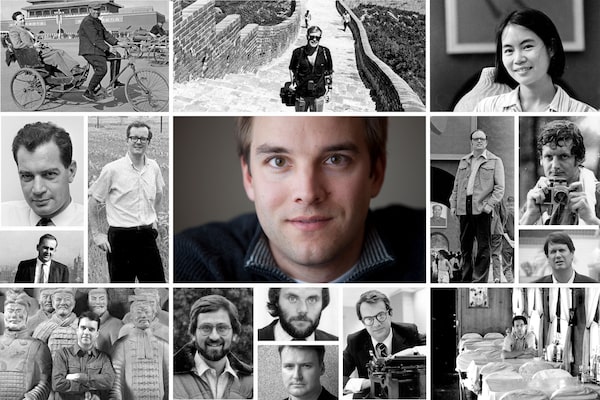

Nathan VanderKlippe, middle, is one in a long line of The Globe and Mail's China bureau chiefs. His predecessors include, clockwise from top left: Frederick Nossal; Charles Taylor; Jan Wong; Ross Munro, John Burns and Geoffrey York; Allen Abel; John Fraser; Bryan Johnson and Miro Cernetig; Stan Oziewicz; Mark MacKinnon; and Colin McCullough, David Oancia and Norman Webster.The Globe and Mail

When the bureau opened in 1959, it was the first permanent office for a Western news organization in the decade since the Communists won power. The Communists were busy transforming the landscape of their country when the first bureau chief, Frederick Nossal, arrived: Here, Mr. Nossal photographed a group of peasants in Xinjiang building canals and planting tough grasses to fight the desert sands in 1960.Frederick Nossal/The Globe and Mail

Charles Taylor, the second bureau chief, saw these children doing outdoor physical training at an experimental primary school in 1964. Mr. Taylor reported on China's massive population growth and the Maoist's struggles to feed them by taking more direct control of rural agriculture.Charles Taylor/The Globe and Mail

In the early 1970s, China and the United States began to bridge the Cold War divide by allowing table-tennis players to travel to each other's countries, now known as 'Ping Pong diplomacy.' Globe bureau chief Norman Webster was with the U.S. team for this sightseeing trip to the Great Wall in April of 1971, less than a year before president Richard Nixon's landmark visit to China.Norman Webster/The Globe and Mail

Mao Zedong's death in 1976 brought the Cultural Revolution to a halt and left competing factions of his party struggling for power. Here, in October of 1976, a rally in Beijing denounces the Gang of Four, a radical group led by Mao's widow that was accused by Mao's successor, Hua Guofeng, of trying to take over the government. The four were arrested and served long prison sentences.Ross Munro/The Globe and Mail

At left, bureau chief Jan Wong's report on the massacre of pro-democracy protesters in Tiananmen Square leads The Globe's front page from June 5, 1989. At right, Ms. Wong sits at her desk in the bureau explaining how she fought off plainclothes security forces who tried to abduct her, one of many threats western journalists faced for reporting on Tiananmen.The Globe and Mail; Will Burgess/Reuters

When Beijing won its bid for the 2008 Olympic Games in 2001, the site they chose involved razing Dragon King Village, a peasant enclave on the city's outskirts. This migrant family came to Dragon King Village to work in local vegetable fields. Miro Cernetig found people in the village upset at the government's decision and fearful they would get nothing in compensation, but they were resigned to move.Miro Cernetig/The Globe and Mail

At left, spectators cheer at the opening ceremony of the Beijing Games on Aug. 8, 2008. 'After decades of isolation, followed by years of uncertainty and timidity on the world stage, this was the moment China had been waiting for, the moment when the eyes of the world were turned upon it, legitimizing its new power,' wrote Globe bureau chief Geoffrey York, right.Fred Lum and Erin Conway-Smith/The Globe and Mail

Police officers, masked to stay safe from COVID-19, guard a side entrance of a court in Dandong, Liaoning province, after the arrival of vans that brought Canadian entrepreneur Michael Spavor to stand trial. Mr. Spavor and a Canadian ex-diplomat, Michael Kovrig, had been detained more than two years earlier in apparent retaliation for Canada's arrest of an executive at Chinese telecom giant Huawei.Nathan Vanderklippe/The Globe and mail

Nathan VanderKlippe

Nathan VanderKlippe