Ravish Garg turns on his blinker to exit the highway after another 15-hour day on the road. The other trucks that have been driving alongside his forge ahead to their own destinations.

One will pass a humble blue WELCOME TO BRAMPTON sign staked in the grass in front of the looming Amazon Fulfilment Centre and drop off a load that includes the dog leash a woman in a Toronto condo ordered for one-day delivery.

It will be boxed by a worker who was sardined on a bus for 90 minutes to get to the warehouse.

Another truck will drive a kilometre and a half north to the sprawling Maple Lodge Farms processing plant – where COVID-19 has infected more than 100 employees in the past year, causing two deaths – to deposit thousands of pounds of chickens, one of which a suburban family in Oshawa will eat for dinner later that week.

Mr. Garg’s load of plastics will be dropped off at a yard in Oakville before heading to the Uline shipping supply factory, whose American CEO has campaigned against COVID-19 restrictions.

And then Mr. Garg, 31, will get into his car and drive to L6P, a postal code in Brampton that has the highest per-capita rate of COVID-19 cases in the province.

He’ll let himself in through the side door of a semi-detached home into his basement apartment, where his fiancée, Anu Sharma, 26, will heat up his dinner: a plate of rajma chawal, kidney-bean curry her future mother-in-law taught her to make over a video call from Punjab.

They’ll talk for an hour before Mr. Garg heads to bed, where he’ll rest for six hours before rising at 2 a.m. for another long day of driving.

In a viral public service announcement in January, Ontario Premier Doug Ford – speaking in Punjabi, L6P’s dominant mother tongue after English – urged Mr. Garg and his neighbours to “ghare raho,” or stay home. Among the more than 82,000 people who live there, few have had the luxury of following that advice. And so many of them have wound up at the local COVID-19 assessment centre, at Brampton Civic Hospital’s ICU or at the local morgue.

In L6P, 89 per cent of residents are racialized, and 66 per cent are South Asian. The median household income is $102,070, which is 45-per-cent higher than the national average, but only because in many homes, several workers pool their earnings. The median individual income is just $26,139. After the first wave of COVID-19, data made clear that race and class were driving forces of the pandemic: precarious employment, lack of paid sick leave, and crowded or multi-generational housing put people at risk for infection and hospitalization. In the third wave, those statistics remain unchanged. Like other neighbourhoods in Montreal, Surrey, B.C., and Toronto, L6P has carried an outsized burden. Residents doing essential work couldn’t stay home. As a result, the test positivity rate has hovered above 20 per cent.

Brampton’s proximity to Pearson International Airport has made it one of the country’s most important hubs for transport and logistics. In 2019, $1.8-billion in goods travelled daily through Peel Region, of which Brampton is part, to other regions in Canada. The sacrifices residents of L6P have made to keep so many other Canadians safe and comfortable have largely been invisible – most of the workplace spread at factories, warehouses and construction sites in Brampton has not been made public, and only three out of five people who get COVID-19 in Peel shared information about their jobs with public health.

Percentage of residents commuting to work

L6P, Brampton

Toronto

Difference in the proportion of commuters

between Toronto and Brampton’s L6P area

Although the proportion of commuters dropped significantly in both the L6P area and in Toronto, a higher proportion of L6P residents continued to commute as compared to Toronto.

A

Ontario declared

state of emergency

50%

40

A

30

20

10

0

July

July

Jan.

2019

Jan.

2020

Jan.

2021

Note: Environics Analytics collects anonymized data from mobile devices with location enabled to see what percentage of people moved more than 500 metres beyond their inferred "common evening location" for a given timeframe. Data are aggregated to the postal code level to ensure it is not personally identifiable.

CHEN WANG AND MURAT YÜKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL,

SOURCE: ENVIRONICS ANALYTICS

Percentage of residents commuting to work

L6P, Brampton

Toronto

Difference in the proportion of commuters

between Toronto and Brampton’s L6P area

Although the proportion of commuters dropped significantly in both the L6P area and in Toronto, a higher proportion of L6P residents continued to commute as compared to Toronto.

A

Ontario declared

state of emergency

50%

40

A

30

20

10

0

July

July

Jan.

2019

Jan.

2020

Jan.

2021

Note: Environics Analytics collects anonymized data from mobile devices with location enabled to see what percentage of people moved more than 500 metres beyond their inferred "common evening location" for a given timeframe. Data are aggregated to the postal code level to ensure it is not personally identifiable.

CHEN WANG AND MURAT YÜKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL,

SOURCE: ENVIRONICS ANALYTICS

Percentage of residents commuting to work

L6P, Brampton

Toronto

Difference in the proportion of commuters

between Toronto and Brampton’s L6P area

Ontario declared

state of emergency

50%

Although the proportion of commuters dropped significantly in both the L6P area and in Toronto, a higher proportion of L6P residents continued to commute as compared to Toronto.

40

30

20

10

0

April

July

Oct.

April

July

Oct.

April

Jan.

2019

Jan.

2020

Jan.

2021

Note: Environics Analytics collects anonymized data from mobile devices with location enabled to see what percentage of people moved more than 500 metres beyond their inferred "common evening location" for a given timeframe. Data are aggregated to the postal code level to ensure it is not personally identifiable.

CHEN WANG AND MURAT YÜKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: ENVIRONICS ANALYTICS

It was 10 months into the pandemic before this city of more than 600,000 got its first COVID-19 assessment centre geared to the South Asian community. It was housed in a space that was both unconventional and familiar to locals: the Embassy Grand banquet hall, where many had attended functions. At the start, staff occasionally had to call ambulances for people struggling to breathe, running high fevers and on the brink of collapse. By early May, those dispatches were sometimes happening multiple times a day.

Priya Suppal, a medical director at the testing centre and a resident of L6P, has had to act as interpreter, social worker and settlement worker for the people who come in. Some worry they’ll lose their jobs or that their families will go hungry if they’re forced to isolate at home. Newcomers fear their visas will be revoked and they’ll be deported. Many women confess they can’t go to a free, government-run isolation hotel because their in-laws wouldn’t approve and instead return home, putting their families at risk. But there are also residents who admit they’ve been to dinner parties and other indoor gatherings. At its peak in mid-April, the case rate in L6P was 663 per 100,000, four times the national average.

“People are scared to come in,” said Dr. Suppal. “They probably know they’re positive and that there are ramifications of having a positive test.”

People line up outside the entrance of a COVID-19 test centre at the Embassy Grand Convention Centre.

The COVID-19 assessment centre at the Embassy Grand banquet hall, which caters to the South Asian community, didn’t open until 10 months into the pandemic.

Dr. Priya Suppal is one of the medical directors at the Embassy Grand COVID-19 testing centre.

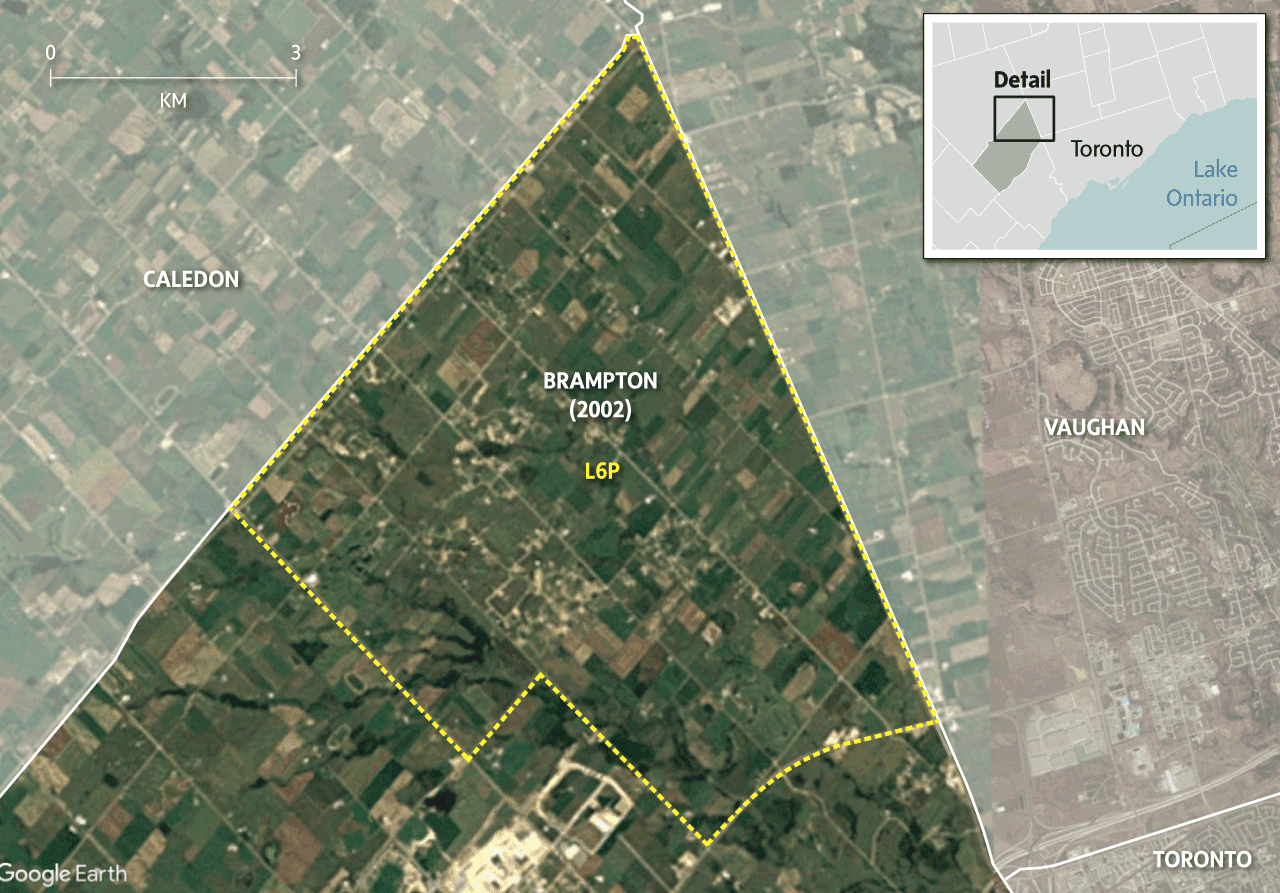

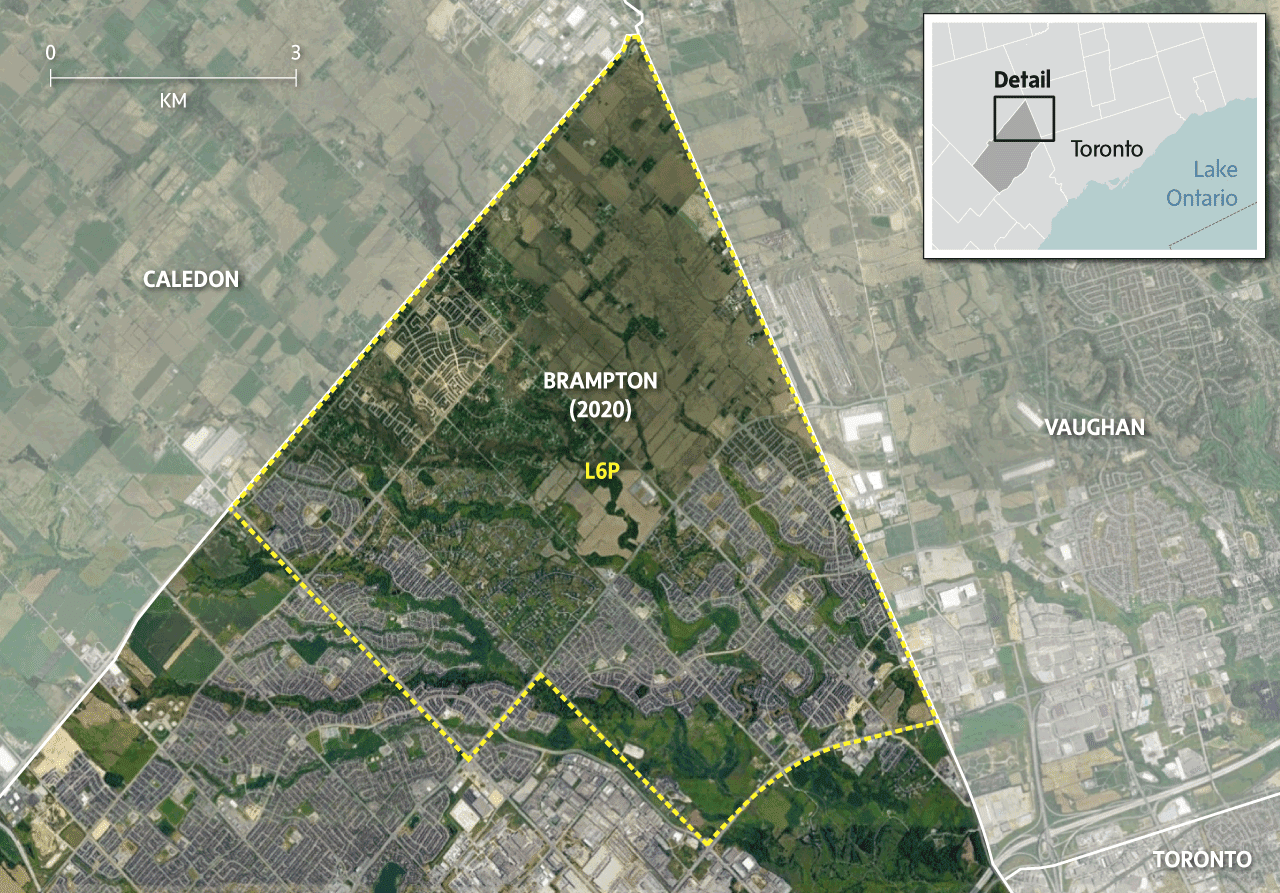

People who don’t know Brampton often think it’s a place exclusively inhabited by taxi drivers and warehouse workers. They might assume residents of L6P are clustered in the kind of aging high-rises that dominate many other neighbourhoods populated by essential workers. But it’s actually a suburban patchwork similar to one you’d find in Langley, B.C., Calgary or Bedford, N.S. – brick-clad townhouses, single-family homes with double garages and McMansions on two-acre plots.

Semi-detached townhomes and multiple cars in driveways on Passfield Trail in Brampton’s L6P postal code area.

Some of the palatial detached houses with pristine lawns are occupied by second-generation Indo-Canadian doctors; others have been converted into multi-unit residences for students. Multi-generational families headed by essential workers occupy many of the more modest homes. A dearth of high- and mid-rise housing has meant most rental stock comes in the form of basement apartments. Pre-pandemic, schools had come to expect that in September they might welcome dozens, if not hundreds, more students than local dwelling counts suggested, because many families living in basement units hadn’t officially been accounted for.

L6P is one of the fastest-growing parts of the country. By 2031, the population is projected to be almost 143,000, according to marketing research firm Environics Analytics – up 68 per cent from 2016, when the last census was conducted. Canada as a whole is expected to grow by 15 per cent in that same period.

The Airport Taxi Association estimates that half of Pearson’s 1,500 drivers live in L6P. That number included Karam Singh Punian, a 59-year-old airport taxi driver with a salt-and-pepper beard and a soft smile.

In the early months of 2020, when COVID-19 was still mostly an international news story rather than a domestic one, the pandemic had already penetrated Mr. Punian’s life. At the time, most COVID-19 coverage on TV news showed scenes from China, Italy and Spain, countries that were beginning to lock down as cases soared. Some drivers would refuse passengers who had flown in from those destinations, but that wasn’t Mr. Punian’s nature. Instead, he’d load their luggage into the trunk of his car and usher them into the back seat. It would be months before the Greater Toronto Airport Authority provided drivers with personal protective equipment and the drivers themselves installed plastic shields in their cars.

The Airport Taxi Association estimates that half of the 1,500 drivers who pick up passengers at Toronto Pearson International Airport live in the L6P postal code.

During the pandemic’s first wave, 10 airport taxi drivers died from COVID-19.

By the third week of March, Mr. Punian began to experience flu-like symptoms and stopped driving. He quarantined in the basement of the house he shared with his family, getting sicker by the day. Struggling to breathe, he was taken to Brampton Civic, then transferred to Toronto General Hospital, where he died on May 4.

His brother-in-law, Birender Maan, said Mr. Punian was proud to provide a home for three generations of his family – especially his granddaughter, a toddler. When she was an infant, Mr. Punian assumed the role of her protector.

“He loved his granddaughter, right?” Mr. Maan said. “When there was a big gathering going on where all the kids were dancing and there was loud music, he’d pick up his granddaughter and go walking outside.”

In normal times, the grieving family would’ve opened their home for several days, pouring endless cups of chai for visitors, Mr. Maan said. Instead, the house was quiet, and nearly 400 mourners were directed online, to a funeral livestream.

In the first wave of the pandemic, 10 airport taxi drivers died from COVID-19, according to Rajinder Aujla, president of the Airport Taxi Association. Of the ones who survived, 80 per cent were put out of work due to the downturn in air travel. The $1,800 a month they get in government assistance doesn’t come close to covering monthly costs, so many have taken out second mortgages or lines of credit to feed their families.

“Nobody was thinking it would be going that long,” said Mr. Aujla. “Most of the people I know are really depressed now.”

The federal government’s decision in April to ban passenger flights from India and Pakistan for a month to keep out arrivals infected with COVID-19, especially deadlier variants, was heralded in the media. How could such international travel possibly be essential?

But to many residents of L6P, travel – typically between India and Canada – was vital. Some travellers were students registered at Canadian colleges and universities who had to physically be in Canada to complete their studies. Others had been granted work permits after years of waiting. There were husbands reuniting with their wives, children with their parents, grandparents meeting their grandkids for the first time.

Manvir Bhangu is the manager of operations at the Punjabi Community Health Services.

While only a small portion of COVID-19 cases are linked to international travel, the structures around mandatory quarantine have been the bigger concern for those assisting newcomers in L6P. Manvir Bhangu, operations manager with Punjabi Community Health Services, says she and agency staff routinely hear stories about unsafe “quarantine hotels” in the basements of local homes. Through classified ads, they purportedly offer newcomers – particularly Indians on study permits – a place to safely carry out their government-mandated self-isolation. But students have complained to the agency that their passports have been confiscated and their units, which they’d been led to believe would have separate rooms and bathroom facilities, were in fact shared with others who should be isolating.

Some newcomers who arrived in L6P this year revealed to The Globe they only knew their neighbourhood was a COVID-19 hot spot weeks after landing in their new home. By day, they risked exposure to the virus at factories that prepared gourmet meal kits or manufactured fire-safety equipment. At night, they’d scour job sites for hours, applying for hundreds of postings in fields in which they’d been trained – IT, sales, engineering – that would allow them to earn more money while working safely from home.

At Castlemore and Clarkway on the east side of L6P, Mr. Garg, the truck driver, lives with Ms. Sharma, a restaurant manager, and a cousin who also works in food service. The three pool their earnings to pay the $1,400 rent on their basement apartment, housed in a recently built semi owned by first-generation Indian immigrants.

Ms. Sharma sends a few hundred dollars to her family in Punjab each month. After finishing the college program she came here to do in 2017, she took the restaurant job to pay bills and get the work experience necessary to obtain permanent residency. But jobs in her field, electrical engineering, are scarce in Brampton, so she, like so many others, has been stuck in low-wage essential work for years.

In her first job, at another local Indian restaurant, Ms. Sharma’s boss underpaid her for months and owed her thousands of dollars. When she worked up the nerve to confront him, he threatened to report her to the government for accepting tips in cash – unreported income he said might jeopardize her application for permanent residency.

“It’s fun and games to blame certain communities for causing cases to go off and all that,” Ms. Bhangu said, “but it’s another to kind of live it and you know, you don’t have a choice.”

To understand how Brampton continued moving throughout the pandemic when much of the country went still, one only needs to look at who is using Canada’s highways. While non-commercial traffic was down by about 90 per cent from 2019 to 2021, weekly truck trips are now more frequent than ever, after a brief dip at the start of the pandemic.

Nowhere is this change felt more acutely than in Brampton. The highways that pass through Peel are the busiest on the continent when it comes to truck traffic. Drivers aren’t just transporting loads from airport-area warehouses to other parts of the country, but also delivering and picking up billions of dollars of goods weekly on either side of the Canada-U.S. border.

Mr. Garg said in the early days of the pandemic, many of the big trucking companies laid off their drivers for a few months, but smaller outfits, including the one he worked for, got very busy. Demand was so high that he was doing six-day journeys from Brampton to Salt Lake City, Utah, and back, subsisting on Subway sandwiches and eggs cooked on the electric stove in his cab. Now he does day trips to the U.S., with only Sundays off to sleep in, go for a walk or binge Netflix with Ms. Sharma.

It was precisely because retail activity slowed in other parts of the country that it picked up for truck drivers and those working in factories and warehouses. Shopping shifted online, which made transportation and logistics – much of which cannot be performed remotely – even more essential.

Brampton residents had to keep moving, too. Of all neighbourhoods in Toronto and Peel Region, L6P has the highest proportion of people commuting to a different census subdivision or division for work, according to a new analysis from the Gattuso Centre for Social Medicine at University Health Network. It also had some of the highest absolute amounts of employment in manufacturing, utilities, trades, transport and equipment.

The majority of workers get to work by car, with some opting for riskier carpools organized through WhatsApp groups or Kijiji ads, where users offer their neighbours lifts from L6P to the Amazon warehouse.

Workers exit a Zum bus as they head in for their shift at the Amazon fulfillment centre in Brampton. The L6P postal code area, where many essential workers live, has seen high positivity rates for COVID-19 infection.

But public transit remains the cheapest option. During shift change at Amazon’s Heritage Road distribution centre in west Brampton, more than 100 people might be waiting to board the eastbound 511 Zum bus. Most wear disposable masks and have backpacks slung over their shoulders. The majority appear to be in their 20s, but after a 10-hour shift, they carry the world-weary expression of people thrice their age. The commute to L6P can be a three-bus, 94-minute odyssey.

In March, the city briefly suspended service on the line after nine Brampton Transit drivers tested positive for COVID-19. All of them drove along the western stretch of the 511 route or one that connected to it. One driver, Dael Muttly Jaecques, died. The decision to suspend service came after the drivers’ union raised concerns that a potential outbreak at Amazon’s Heritage Road centre was the source of driver infections.

It didn’t take long for Amazon to launch its own private bus service to ensure workers could still get to work. Ultimately, it only ran for a few days before Peel Public Health closed down the fulfilment centre for two weeks after a testing blitz caught more than 200 employee cases of COVID-19.

One employee at the facility, whom The Globe has agreed to not name, described a long and difficult process to get medical leave to self-isolate, which deters employees with symptoms from calling in sick.

Last winter, the employee’s mother, a front line health-care worker, died of COVID-19. His grandparents were infected, too. The three generations lived together, and the employee feared he might also be sick. To get medical leave, the company required proof in the form of his family’s COVID-19 test results. The employee, who was mourning his mother’s death and had been ferrying his grandparents back and forth to the hospital, where they were both admitted and discharged multiple times, was livid. It was three weeks before his leave was approved – three weeks with no pay.

When the facility closed in March, the employee said he wasn’t surprised. “That’s probably why they had so many cases – because nobody really wants to go through the whole process of not being paid, like me,” he said.

After getting off a Zum bus, workers head to their shifts at the Amazon fulfillment centre in Brampton.

When the fulfilment centre reopened, hundreds of seasonal workers had been laid off, and the company had created a new protocol for entering the building through different entrances. But every few days, the employee received an automated text from Amazon notifying him that co-workers had tested positive. Amazon did not respond to The Globe’s questions.

On April 24, the Heritage Road warehouse and another in neighbouring Bolton were partially shut down – two of 25 workplaces closed in Peel from April 24 to May 11 under a new rule to shutter any business with more than five positive tests.

Edesiri Udoh, who worked as a health promoter with Wellfort Community Health Services, which provides outreach in several Brampton communities, including L6P, says workers often tell the agency’s staff they can’t get time off, even to get a COVID-19 test. Some symptomatic workers confessed their employers had told them they could briefly leave work to get tested but were expected to return and continue working as they waited for their results. In January, Peel Public Health analyzed cases of people who had tested positive for COVID-19 and found that almost one-quarter of them continued going to work after the onset of symptoms.

Ms. Udoh, Ms. Bhangu and many health care leaders, including Peel’s chief medical officer, Lawrence Loh, have stressed that the single biggest policy change necessary to bring down COVID-19 numbers in Brampton is paid sick time. In April, the province instead introduced a three-day benefit, which many health and labour advocates say was inadequate. If an employee was sick or exposed to COVID-19 and had to isolate for 10 days, what would happen on day four?

Peel Public Health has found another way to protect workers: by bringing vaccines to job sites. In late April, Maple Leaf Foods and Maple Lodge Farms opened mobile vaccination clinics at their factories. The following week, Amazon followed suit. The employee The Globe spoke to said staff were offered $50 in exchange for getting jabbed.

But besides those public-private partnerships, there was a feeling that Brampton was being snubbed in the provincial vaccine rollout. The doses they received initially fell short of the per-capita allotment they were promised. Of the 325 pharmacies that began offering vaccines in early March, none were initially in Brampton. In April, when provincially identified COVID-19 hot spots in Toronto started opening pop-up clinics for residents over 18, it was weeks before Brampton received provincial approval to do the same, despite having far higher positivity rates. As of May 10, 40 per cent of eligible residents in L6P had received their first dose of the vaccine.

In late April, Dr. Suppal had a phone appointment with a long-time patient who’d tested positive for COVID-19. The man and his wife lived in a house with a basement apartment occupied by their daughter, son-in-law and two grandchildren.

It was immediately clear to Dr. Suppal that her patient needed urgent medical attention – he could barely get a sentence out. “You’ve got to go to the hospital. You need to call an ambulance,” she told him.

The man’s wife had been the one to bring COVID-19 home – she’d contracted it at the distribution centre where she worked – and was in no shape to take him.

“Well, can I get my daughter to drive me?” the patient rasped.

Dr. Suppal explained that since his daughter and her family were all healthy, they’d be risking exposure to the virus. Eventually he was transported to Brampton Civic Hospital by ambulance, where he received dexamethasone and oxygen. The next morning, Dr. Suppal received a note that her patient, now stable, had been transferred 110 kilometres away, to a hospital in St. Catharines, Ont., because Brampton Civic needed the bed. Since April, an average of 116 patients each week have been transferred out of Brampton to other hospitals in Ontario.

On the ground at the Embassy Grand testing centre, Dr. Suppal sometimes saw up to seven people from a single home – grandparents, parents and children, living under the same roof. (While the average household size in Canada is 2.4, in L6P it’s 4.4, the highest of any postal code in Toronto and Peel Region.) Some of these living situations are by choice, but many are out of necessity: Childcare can be prohibitively expensive, and culturally appropriate or affordable senior living options are limited.

An elderly woman is helped to the entrance of the COVID-19 test centre at the Embassy Grand Convention Centre.

In these multi-generational homes, Dr. Suppal encountered complicating factors that extended beyond illness. While doing mass testing at a major distribution centre in Brampton, she informed employees that if they tested positive, they should take advantage of government-funded isolation hotels to protect the people they lived with. But many of the South Asian women told her their in-laws wouldn’t allow it, even if they were sick.

“The expectation, certainly in our culture, is sometimes, ‘Who’s going to cook the meals, and who’s going to look after their children, and who’s going to clean the house?’” she said.

She has also learned from living in L6P and working on the front lines that despite the dominant media narrative, COVID-19 isn’t spread exclusively through workplace exposure.

Until the third wave hit, L6P resident Yudhvir Jaswal, the CEO of Y Media and a prominent Hindi, Urdu, Punjabi and English broadcaster, routinely heard from listeners that coverage of COVID-19 was overblown. Many were tuning into Mr. Jaswal’s programs while also following news back home, and until the most recent variant-driven wave hit, the impression was the Canadian government was overreacting with restrictions.

Even a month ago, in the early stages of India’s current wave – which has seen thousands of daily deaths and brought the Indian health-care system to the brink of collapse – Mr. Jaswal said there was sometimes a disconnect between the images on TV screens and what people were hearing from their families back home. Those reports seemed to carry greater weight in helping them assess the situation than news reports. When he’d probe them about daily infection rates or death counts, they’d reply, “No, no, no, no, I don’t know where it is happening. Maybe in Maharashtra or Delhi, but in Punjab, everything is fine.”

“There was a time when people would say, ‘COVID is nothing,’” he said of some of his neighbours. “They are still having parties every day.”

Realtor and local Punjabi radio host Deepak Punj, who lives on the eastern border of L6P, on a street lined with four-bedroom detached homes, said that by last summer, lockdown fatigue had set in. A family nearby hosted a party for 40 people inside their house, and while he and his neighbours griped about it, nobody reported it. In September, at the start of Ontario’s second wave, one prominent resident threw an extravagant multiday wedding, where more than 100 guests gathered inside or closely under a tent, most of them unmasked.

“In our community, they feel proud to break the rules,” said Mr. Punj. “They think they’re some kind of VIP.”

Dr. Suppal is often thankful for the mask and shield that cover her face, so the people she sees at the testing centre can’t read her expression when they explain how they think they might have been exposed: driving maskless with a friend, attending a dinner party or some other forbidden social activity.

“I don’t want to say this, but I feel like there’s a flagrant, ‘I’m not going to listen to the rules, they don’t apply to me,’ where you see multiple cars in driveways that don’t belong there, gatherings that don’t belong there,” she said.

Ravish Garg (left) and Anu Sharma stand outside their basement apartment in the L6P neighbourhood in Brampton.Baljit Singh/The Globe and Mail

On May 6, to much praise, Peel opened up vaccine booking to anyone over 18. For so many Canadians, the vaccine is seen as the pandemic’s exit ramp, the way back to the life COVID-19 put on hold. But little in Mr. Garg and Ms. Sharma’s day-to-day routine will change. They hope to finally get married this year, but are unsure of when it will be safe to fly to Punjab or have their families come here.

The couple want to book their vaccine appointments together on a Sunday, Mr. Garg’s day off, so they can rest at home and take care of each other in case they experience side effects. The following morning, Mr. Garg will leave home at 3 a.m. to pick up the day’s load at the truck yard. Ms. Sharma will smile sweetly behind her mask while reminding customers at her restaurant to pull their own masks over their noses. They will go back to work.

Additional reports from GUNDEEP SINGH and CHEN WANG; Photography by FRED LUM and BALJIT SINGH; Video by FRED LUM; Graphics by CHEN WANG and MURAT YÜKSELIR; Editing by NICOLE MACINTYRE, DAWN CALLEJA, TABASSUM SIDDIQUI and CAROL TOLLER; Photo editing by SOLANA CAIN; Video editing by TIMOTHY MOORE; Design and development by DANIELLE WEBB

Translation services provided by Worldwide Express, with editing by Sonali Verma, Manzoor Kasi, Darshana Thaker, Swati Matta and Manan Gupta

Dakshana Bascaramurty

Dakshana Bascaramurty